Last week, the Facebook Data Team released its social network analysis research, Anatomy of Facebook (on Facebook of course!). They have annotated their algorithms in two academic papers The Anatomy of the Facebook Social Graph and Four Degrees of Separation. Facebook claims their data show that connectivity between people around the world has dramatically increased – so much so that we are only four links away from someone in the most remote part of the world, whether that is a tundra or rainforest. A sociological look at the data dispels this notion. Despite its impressive sample, which includes 721 million active Facebook users and their “69 billion friendships”, Facebook’s findings replicate widely-held sociological knowledge about the way people form social ties. Nonetheless, Facebook’s data has great potential to address important social questions, if we can just set aside those pesky social science concerns about research ethics, informed consent and privacy…

Facebook’s study has an extraordinary sample of ‘active users’ representing one tenth of the world’s population The term active user is defined by Johan Ugander and colleagues in one of the aforementioned academic papers. This refers to someone with at least one friend who had logged on once in the past 28 days from the study’s commencement in May 2011. This is less frequent than the Facebook’s company definition of an active user, but the divergent definitions are not explained. For the record, Facebook currently reports it has 800 million active users and 50 percent of them log in at least once a day. Lars Backstrom, computer scientist and one of the Facebook Data Team’s lead researchers in this study, reports on the aims and key findings. The Team found that only around 10 percent of active users have less than 10 friends, while half have a median of 100 friends (the average is 190 friends). See below for more detail.

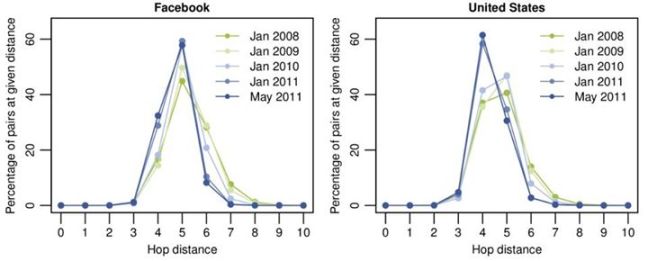

“Four degrees” of separation?

Facebook’s researchers are claiming that the small worlds thesis developed by Jeffrey Travers and Stanley Milgram, also popularly linked to Duncan Watt’s six degrees of separation research, is wrong. Facebook says that there are only four degrees separating me from you, dear readers.

Facebook is making big claims about this research. The researchers argue that all active Facebook users are potentially connected to someone in Siberia as well as to someone in the Peruvian rainforest. My background is Peruvian – I can tell you right now that even though I’m connected to my cousins in Peru on Facebook, none of us have any connections to people living in a rainforest! Not in real life, let alone on Facebook. This is because, as Facebook concedes, the majority of people on Facebook (84%) are actually only connected to other people in the same country where they live. Moreover, Facebook notes that people’s friendships are clustered around the same age groups (see diagram below).

The potential reach of Facebook to bridge social gaps at the global level is actually limited by the same demographical concerns as in real life. In sociology, we know this as homophily: people form friendships, romantic relationships and other social connections with people based on their socio-cultural, geographic and demographic similarities. For example, sociologists Miller McPherson, Lynn Smith-Lovin, and James Cook find that race and ethnicity are the biggest influences on social networks, followed by age, religion, education, occupation, and gender. The above graph on the age correlations between Facebook friends should therefore come as no surprise.

I’m really pleased that Facebook is releasing this type of data. This is commendable because a lot of companies that push out ‘research’ about social media usually only pump out infographics but they do not make their methodology or data available to others. (For a very recent example released yesterday, see a study claiming that women gamers have more sex, republished in reputable sites such as Mashable and VentureBeat. The findings seem suspect when we consider the study was commissioned by… a gaming site.)

How sociology can improve Facebook

Despite its progressive approach to social media research, Facebook could greatly benefit with more sociological analysis to make their data more meaningful. I remember reading in The Economist (from 2009) that Facebook has hired at least one sociologist, Cameron Marlow, to develop their social network research. He has contributed to this Facebook study. Still, as an applied sociologist, I am left wanting. What does it all mean? Mathematical sociologist James Coleman would have had a field day with this wealth of data. Coleman (and other social scientists since) have been interested in social networks as a type of social structure – a microcosm of culture in a particular society, affected by social institutions and informal social norms about trust, obligations and expectations of what type of support we can expect from other people. Facebook’s research tells us about the links between a large sub-group of humanity – but it doesn’t say anything about what these connections mean.

If most people have 100 to 190 friends on Facebook, as the FB research suggests, are these strong ties that provide bonding social capital, where people trust and help one another effectively increase their socio-economic position? (See Alejandro Portes‘ research.) Are Facebook friendships mostly weak social ties (such as casual acquaintances, old school friends and former work colleagues) that are good for seeking out new job opportunities, but not so good for emotional support? (Refer to Barry Wellman‘s classic research.) Are Facebook friends bridging ties that help might help someone find new ideas from outside groups and which facilitate civic cooperation? (See Robert Putnam.) Do people on Facebook have linking ties to important people who can lend their social prestige to important causes? (See Nan Nin.)

Other sociological questions relate to what friendship connections are actually doing on Facebook. Are people merely exchanging hilarious GIFs and links to cute videos or are they exchanging information that improves their quality of life? Why are some groups of people more likely than others to set up successful support groups on Facebook that mobilise social action? What are the cultural differences within different sub-groups in different countries? It seems unlikely that all 721 million active Facebook users are using FB in the same way. Other research identifies qualitative differences in the way people use the internet in different countries, as well as differences between sub-populations within the same country. (For example see Caroline Haythornthwaite and Barry Wellman’s research.) Reynol Junco’s American study finds that students who regularly use Facebook to collect and share information achieve good high school scores (this includes people who regularly check in with what friends doing and who share links). In comparison, users who simply socialise on Facebook (updating their status and chatting) have poor educational outcomes. Clearly, Facebook friendships and their activities have different real-life benefits, so greater connectivity alone tells us little about the social networks on Facebook.

Hopefully Facebook will release other papers addressing the sociological dimensions of networks. It would be useful if Facebook was somehow able to de-identify at least a representative cut of the data and make it publicly available for other researchers. Then again this brings up a major methodological issue: Facebook did not seek approval from users to use their data. While there are ongoing debates about the ever-changing privacy policies on Facebook, most of this discussion is about how personal data is being used to deliver targeted advertising. The research conducted by Facebook on friendship activity does not feature heavily in such debates. This presents an important ethical dilemma for social scientists, given that informed consent and transparency with research participants is central to social research.

Does anyone have any thoughts about Facebook’s ‘four degrees of separation’ study? Can you think of other questions you’d like Facebook to address? What about the methodological and ethical ramifications of how the data are collected – do you have any concerns or further comments? Please share!

All graphs via Facebook

Connect With Me

Follow me @OtherSociology or click below!

wow…very very exciting

LikeLike

Thank you very much.

LikeLike

What a great post, and thanks for all the links to helpful reasearch.

LikeLike

Thank you! You’re welcome!

LikeLike

I was just thinking that yes, the 6 degree thing has got to have been reduced, though it may not have extended all the way to the rainforest. Just think how many people check out George Takei’s site (for example). That’s gotta knock a point off the scale on it’s own. What I’m trying to figure out is how real social interaction has been replaced (supplemented?) by virtual interaction these days – having woken from a 10 year marital nap and learning that the world has changed without me. People may be connected, but how are we connecting?? Especially those blessed with “otherness.” Hmm…

LikeLike

Hi Barbara. Thanks for your comment and question. The social science research shows that social media enhances connection largely with people from our pre-existing social circles. This is especially the case on Facebook, where people predominantly “friend” people whom they already know offline. Other social media connects us to strangers, but again the research suggests a similar trend, where people are connecting with people who largely think they way they do and who belong to similar socio-economic backgrounds. So in a sense, these connections are not necessarily diversifying our networks.

On the one hand, this can be helpful to people who are from minority groups who are Othered, and who may not have a strong support base if they are socially isolated from people of the same background. On the other hand, it doesn’t necessarily improve diffusion of ideas into new networks.

I’m glad to see you commenting on blogs after your 10 year hiatus! Hope to hear more from you in future.

LikeLike

Thanks for writing and sharing your thoughts, Barbara. I’m sorry but your comment has been locked in my spam filter and I’ve only just seen it. The point of my article is not that the six degrees has been reduced as Facebook claims. It’s that Facebook’s measure is lacking. It examines connections without social context. Not all interactions on Facebook are meaningful. The “six degrees” thesis has been critiqued and revised, as drew from a specific set of literature and limited sample set. The gap is wider for some groups than others. Moreover, the point of the study is not so much how close or far our connections are, it’s more about how these relationships eventuate and what they can be used for. Duncan Watts has shown how “weak ties,” that is, casual acquaintances such as work colleagues we don’t don’t see often, can help our socio-economic mobility (or not, as the case may be). Many people read George Takei’s site, but who are his readers? How do they understand and act on his writing? What does it mean that he has a huge readership? It means he’s a famous actor who is now prolific in his social media use. He does some great advocacy for human rights issues, especially for LGBTQ issues. But what does the public make of this? Does he persuade all his fans, or does he only persuade his fans that already agree with his viewpoints? This is another issue I’ve addressed in my article: social media is only meaningful when we understand how people’s online connections translate into their offline actions.

Elsewhere, I’ve shown that people’s Facebook activity, and their social connections, mirrors or enhances their offline ties. So to use your language, social interaction has not been replaced or supplemented by virtual ties, but instead, online connections enhance or amplify what happens offline.

Not sure what you mean by “blessed with ‘otherness.'” If you read my page on “What is Otherness” you’ll see that this concept is about how societies draw up false dichotomies of difference. Some groups are seen to be different, or Other, and this is not a good thing. It reflects power relations, where some social groups are stigmatised because they are different.

I think the last question you end on is a good sociological one: how are we connecting? Online connections are uneven depending on age, culture, access to technology, and so on. Even in developed nations like Australia, people living in the country or in remote areas still have inadequate access to the internet. So while some people living in rainforests may have access to Facebook, other people, such as in conflict afflicted areas like the Republic of Congo, still rely on mobile phones rather than the internet. Facebook seems ubiquitous, but it is not, which is why Facebook is spending a lot of effort and resources to improve web connectivity in developing regions!

LikeLike