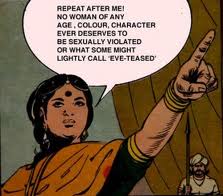

Public harassment of women in India is known as ‘Eve teasing’. I’m using this as a case study to highlight the ‘Western’ media’s divergent constructions of sexual harassment at home and abroad.

In Australia and in Western countries such as the USA, the mainstream media tend to portray sexual violence and gender oppression as a barbaric practice that are culturally entrenched in developing countries. Gender violence is the stuff of others – it is something that members of ‘less civilised’, less enlightened societies do. In comparison, the Western media depict sexual harassment and rape in their own societies as fear-mongering events involving individuals, rather thananindictment of an entire culture. (See my discussion of the sociology of crime reporting in an earlier post.)

Today’s post begins with a case study of Eve teasing in India before moving on to discuss sexual violence on a global scale, including the ‘Slutwalk’ movement. I provide more detail on the USA and Australia to illustrate that gender violence against women is widespread in advanced, liberal democracies, as it is in other parts of the world. As today’s discussion is focused on women, I talk only briefly about sexual violence against men but I will return to this issue in the near future. Here, I will argue that the situation in India is one public expression of broader global patterns of sexual assault.

‘Eve Teasing’ in India

India is one of the world’s fastest growing economies, and levels of technology and education are rising rapidly (as reported by UNESCO, p. 19). Despite India’s socio-economic advances, the public harassment of women by men is pervasive. This practice is apparently so routine that it has a special name: ‘Eve teasing‘.

The BBC reports that two young men recently died in Mumbai trying to defend their friends from Eve Teasing. Only now is the law adopting a ‘zero tolerance approach’ to the problem. The death of these men is a very sad loss for these men’s families and their communities which cannot be understated. The tragedy is compounded given that it should not have happened in the first place if social policies and law enforcement had been more proactive.

The Delhi Government’s Department of Women and Child Development already had compelling data that Indian women faced daily sexual harassment, as it had commissioned the UN and other non-government organisations to carry out a study on this topic in 2010. Last year, the BBC reported that the findings from this study ‘confirm what the people of Delhi have known for a long time – that the city is unsafe for women’.

A ‘Slutwalk’ protest (also known as Besharmi Morcha) was held in Delhi at the end of July this year to highlight the daily violence and abuse that Indian women experience. Slutwalk protests began in April, in Toronto Canada. They were in response to the sexist comments that a police constable made to a group of students at York University’s Osgoode Hall Law School during a health safety seminar in late January. The constable said to the students:

You know, I think we’re beating around the bush here… I’ve been told I’m not supposed to say this – however, women should avoid dressing like sluts in order not to be victimised. (Via The Guardian).

These remarks sparked a series of protests in various cities around the world. The Slutwalk Toronto website mobilised the global action. The organising group explained in late February:

We are tired of being oppressed by slut-shaming; of being judged by our sexuality and feeling unsafe as a result. Being in charge of our sexual lives should not mean that we are opening ourselves to an expectation of violence, regardless if we participate in sex for pleasure or work. No one should equate enjoying sex with attracting sexual assault.

The Slutwalk movement is not without its controversies, especially in Delhi (see the suggested readings below). Nevertheless, the idea behind this social movement goes to the heart of Eve teasing and its hidden sociological causes. Sexual harassment betrays a simmering culture of sexual violence. Whether it is in the form of a careless joke, a sexist comment or a public taunt, sexual harassment perpetuates a sense of fear. Public harassment requires urgent social intervention because it can be a precursor to escalated violence.

Specifically, there is a connection between public forms of harassment and rape. The BBC reports that the National Crime Records Bureau in India recorded around 22,000 rape cases in 2008, which was 18 percent higher than four years prior. As one of the Slutwalk Delhi protesters told the BBC:

There are a lot of problems for women in Delhi because a lot of women do face sexual harassment and just a couple of weeks ago the chief of police of Delhi said that if a women was out after 0200 she was responsible for what happens to her, and I don’t think that’s the right attitude.

Eve teasing may seem extreme and it may even play into stereotypes that people in advanced nations have about gender violence: that it is something that happens in countries that have a highly traditional gender structure. For example, Australians hear and read stories about rape, torture and imprisonment of women in other countries, but these travesties of justice evoke pity or indignation for other women in distant lands, rather than reflection about sexual violence everywhere.

The United Nations reports that half a million women were raped during the 1994 Rwandan genocide; 5,000 women are victims of so-called ‘honour killings’ annually; and 140 million women and girls have undergone female genital mutilation. Women are jailed for speaking out about rape, such as in Afghanistan. Since 1999, over 3,000 women have been attacked with acid in Bangladesh alone, with thousands more cases in other South Asian countries.

These examples are rightful cause for international outrage and political action. The violation of women’s freedom and safety needs to remain in the spotlight as an international human rights issue that requires collective lobbing and support.

At the same time, as the media sensationalises sexual violence and gender oppression in other countries, harassment and abuse seem like something that other people do in other distant places. International data suggests otherwise. Sexual harassment and sexual violence is pervasive all over the world.

Sexual Harassment Around the World

As I previously reported on Sociology at Work, the United Nations finds that up to 70% of women and girls around the world will be beaten, coerced into sex or abused in their lifetime. The UN also finds that women aged 15 to 44 are more likely to experience rape or domestic violence than they are at risk of developing cancer, being in a traffic accident or contracting malaria – one of the world’s deadliest diseases.

Yesterday, The New York Times reported on an American study which finds that sexual violence is widespread in the USA. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey was conducted by the National Centre for Injury Prevention and Control at the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCP). The study surveyed a nationally representative sample of 16,507 adults. It found that around 20 percent of the women reported that they had been raped or that they had experienced an attempted rape. A quarter of the women had also been beaten by an intimate partner, and another 16 percent had been stalked.

In Australia, the latest figures by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) find that there were almost 17,800 victims of sexual assault reported to the police in the year 2000 alone. The overwhelming majority of recorded victims are women (85%) and a quarter of these victims were children aged 10 to 14 years. (To read more on combating child abuse, see my post on Sociology at Work.)

Governments and law enforcement agencies rely on population surveys rather than simply on official statistics in order to gauge a more representative estimation of the number of people who are assaulted. This is because violence and abuse often go unreported via official channels. The ABS reports on the Australian component of the International Violence Against Women Survey. The study was conducted during 2002 and 2003. It included 6,677 women aged between 18 and 69 years. The study found that close to 60 percent of these women had experienced at least one sexual or violent crime. Around a third the women had experienced sexual violence by a former or current partner (34%), a third by close family or friends (27%), and one fifth was attacked by an adult figure during their childhoods (16%), or by a parent (2%). One percent of these women were raped by a stranger. Only 14 percent of the women who experienced violence by an intimate partner reported it to the police and 16 percent of those who experienced violence by a non-partner reported the crime to the police.

Men are also victims of rape, sexual and domestic abuse. The CDCP study finds that one in seven men report experiencing severe violence by an intimate partner and up to two percent report being been raped, predominantly as children aged under 11 years. The ABS data show that 15 percent of sexual assault victims in 2010 were male. Male are less likely to report sexual violence due to added social stigma attached to male rape victims, so official figures underestimate its prevalence. As mentioned, I will tackle this issue separately in a later post. For the time being, I’ll address the simple ways in which the average person can tackle sexual harassment, and how sociologists can progress broader social change.

How Can Sociology Help End Street Harassment?

Clearly, the Delhi data from 2010 and the Slutwalk protest in India earlier this year should have been taken more seriously by the Indian Government. It’s shameful that it has taken the death of two men for officials to take the sexual harassment of Indian women more seriously.

Speaking from Australia, media images and stories such as this makes it seem as if violence against women is a bigger problem in ‘other’, ‘less civilised’ parts of the world. Yes, class and caste inequalities are deeply embedded in Indian society, but class inequality is an issue all over the world. Poverty is not an adequate explanation for sexual harassment. Rape and public assaults on women happen in India’s largest cosmopolitan cities where affluence, technology and education are rising. Public shaming, name calling and harassment may seem to be out of control in India, but Eve teasing is actually indicative of global gender practices. Law enforcement officials and researchers in America, Australia and elsewhere agree that sexual assault and domestic violence crimes are alarmingly high, and yet we know that many of these crimes go unreported.

Sociology can help in the first instance by making the data I’ve discussed part of an ongoing public dialogue about the reality of sexual violence. The main way sexual assault permeates the public’s consciousness is with respect to extreme gender oppression ‘overseas’ (that is, anywhere but ‘here’). In Australia, America and elsewhere, the media regularly depicts rape and sexual harassment as something perpetrated by strangers, but the scientific evidence shows that sexual violence is a familiar part of many people’s lives that goes unrecorded and unacknowledged.

One percent of women who are raped in Australia are attacked by strangers – that means that 99 percent of women who are raped, beaten or abused are assaulted primarily by their partners, family members, friends or by someone they already know. The travesty is that these figures are not getting through to people. Instead, these crimes are silenced – in up to 60 percent of cases, as inferred by the data I discussed. People continue fearing strangers while victims are forced to live with feelings of shame and fear alone.

It is a cliché for sociology to suggest education is the answer, but this is a truism for good reason. I don’t simply mean by focusing on the next generation going to school, although sexual education in schools should most definitely cover sexual violence. I also mean expanding the boundaries of public discussion through information, honesty and compassion. Media images make sexual violence into something exotic: it happens in ‘bad homes’, to ‘other’ women who are too afraid to leave their partners – but it doesn’t happen to men… or so we are led to believe. It happens, ‘somewhere else’ – in other countries, where people are poor and less educated. Now you know this is not true. Yes, sexual violence occurs in developing nations and some of these gender crimes seem especially horrific (rape, genocide, unjust imprisonment, and mutilation). Sexual crimes in Australia may not seem so extreme by comparison but this is not a useful way to think about the problem. To view some forms of gender violence as more or less severe than others does further violence to victims of sexual crimes everywhere. Culturally moralistic comparisons ensure that sexual crimes become normalised, rationalised and accepted.

Sexual violence and harassment are just as common in advanced nations as they are everywhere else. Sexual crimes happen in blossoming economies, like in India, where technology and general levels of education are growing, and it happens in homes all around Australia and all over America. It happens to men. It happens to children, it happens to adults. Individuals and societies need to move away from the way we view, excuse and silence sexual harassment and violence.

Public education on this issue means working with law enforcement officials to support their work with local communities, to help them establish empathy and rapport, so that victims might feel more confident in coming forward. Sociologists can also work to connect community support groups, government agencies, police, schools and workplaces. Applied sociologists are especially adept at facilitating social exchange between different publics and professional bodies. We are in a prime position to shape social policy through considered engagement with decision-makers. Everyone would agree that sexual and violent crimes should be brought to justice, but this can’t happen when official processes prevent victims from speaking up for themselves, or where rape and violence are constructed as some isolated, foreign event, making survivors too afraid to report their experiences to the police.

Sexual harassment and sexual violence are not simply something that happens in faraway places. The shame and stigma heaped upon victims of Eve teasing in India is but one manifestation of the sexual and physical abuse that women, men and children live with every day all over the world. Thinking that some forms of gender or sexual violence is more or less barbaric than another doesn’t help. Talking about sexual harassment, assault and rape in an open, respectful and honest way does help.

This is the first of many future contributions that I will make towards breaking down the ‘otherness’ of sexual violence. (By otherness, I mean the negative attribution of difference and the marginalisation of minority or less powerful groups). I’ve got a couple of posts lined up about youth sexuality and pornography, which I hope will further demystify the shame that societies heap upon sexual behaviour and the misinformation about sexual coercion. I hope that if you read this – even if you disagree with me in any way – that you will tell at least one other person and get a conversation started. The next time you see a media report that drums up the gravity of gender violence in another country, have a chat with someone about it. When a crime report focuses on perpetuating a fear of rape solely directed at strangers, remember this post. Then have another conversation with someone else. And keep that conversation going because sexual harassment and violence doesn’t go away by pretending it’s not happening right here, right now.

Learn more

- The United Nations Say No To Violence Campaign

- Eve Teasing

- Slutwalk Toronto

- Slutwalk Delhi/Arthaat Besharmi Morcha

The United Nations Say No To Violence Campaign

- Read my overview of the actions you can take against violence or check out the United Nations Say No/Unite page.

- Watch and share the United Nations video: Youth Voices on Ending Violence against Women.

Eve teasing

- For a different perspective than the one I’ve presented, read a passionate piece on Eve teasing by young bloggers on Critical Thinkers.

Slutwalk Toronto

- Explore the Slutwalk Toronto link I referred to above and read how the organisers conceived the re-appropriation of the word ‘slut’ for their social movement. The rest of the blog is worth reading to see how they’ve expanded their focus to other issues such as bullying, religious condemnation of queer sexualities, and a wonderful reflection on the meaning of social ‘privilege‘ and how it affects various marginalised groups.

- Lisa Wade provides another useful analysis of the Slutwalk movement in North America on Sociological Images.

Slutwalk Delhi/Arthaat Besharmi Morcha

- Check out the Facebook page used by organisers of the event and he Facebook video that promoted it – note that the focus of the campaign was not just on women, but also on men who support the cause.

- Blogger Nandita Saikia provides a thoughtful analysis of Slutwalk on Cold Snap Dragon, arguing against social critiques that it is a movement for privileged women.

- Global Voices covered the Slutwalk Delhi in great detail. I recommend their media hype wash-up.

- Watch Trishla Singh, Media Coordinator for Slut Walk Delhi, discuss the idea behind the event and the appropriation of the word ‘slut’ in an Indian context. (via Global Voices).

Connect With Me

Follow me @OtherSociology or click below!

Great post!

LikeLike

Thanks very much!

LikeLike

Hi Dr OS

Thanks for article. I like your argument that gender violence in ‘other’ places is represented in mainstream media as being about culture, while gender violence in Australia / US / other western countries it is represented as being about the aberrant individual. I’d never thought of it that way, but it matches what I’ve seen. A useful take, thank you.

I have some questions I’d like to hear your views on.

First is about ‘Eve-teasing’. What a name, and what a concept! What kinds of behaviour are referred to by this term in Indian media? As a play of gender politics it’s a master-stroke. To middle-aged Aglo me ‘teasing’ evokes primary-school ptactices of name-calling and pulling pigtails, or alternatively friendly sorts of sexy play. ‘Eve’ evokes a ‘venus from the waves’ image, an archetypical female form draped in cloth, coy and provocative but in no way individual or even human. So ‘Eve- teasing’ as a name for sexual harassment and assault? !!! What the hell does this naming mean and do to those who use and hear it?! It says ‘it’s a little thing, it’s trivial, it’s natural, what’s wrong with you can’t you take a joke? It’s because you wore those clothes, of course they assaulted you, they thought you were asking for it’. And so on. Establishes framing rues: it’s not OK to complain. Feeling rules: it’s not OK to feel angry. I want to know where the expression came from and how it’s used.

Next is about your comment ‘Sexual violence and harassment are just as common in advanced nations as they are everywhere else.’ Is this actually so? Do you think there is more violence against women in places where people are so tragically disenfranchised that violence has become a normal currency of survival? (If this is the case, does the cultural ‘othering’ criterion in play here really reflect a continuum of how pillaged and impoverished and inequitable our lands and cultures are?)

And I wonder how the connection between violence and sex fits in. Mainstream entertainment in western cultures represents violence as sexy. Violence as entertainment, and domination of a weaker person by a stronger as titillating, esp if performed by the hero male to an admiring audience. I can’t escape the feeling that normalising the idea of domination/submission as sexy creates a culture in which violence against weaker people or those who are ‘other’ will feel normal. Can you say something about your take on this?

Finally I wonder what a different twist on our basic concepts might turn up. Gender is a fundamental category here but it’s not the only one in play. What happens if we look at violence not in terms of gender but in terms of an exercise of power, by the stronger against the lesser. In most places women as a category have less power (on many measures) than men as a category, so belonging to the category ‘woman’ identifies a person as being of lesser status. As does belonging to the category homosexual, or poor or uneducated or disabled or dark-skinned – the list goes on. Power relations are negotiated locally in varying ways but a basic hierarchy provides the frame against which this takes place. And when hierarchies are sexually charged, sexual violence feels normal. What happens if we see violence as a means of enforcing power hierarchies, or of resisting them, or of enacting helplessness in the face of immovable hierarchies (such as the mines that have taken your land and destroyed your place and your culture) by being violent toward those on the next step down?

Thanks for creating such provoking work. More please!

LikeLike

Hey Meg,

Thanks so much for your wonderful questions! You bring up lots of things I’ve thought about and some of these I definitely should have addressed in this post. Others are planned for later posts! Your questions were detailed, so my response is lengthy.

Firstly a warning for other people: TRIGGER WARNING: I DISCUSS SPECIFIC FORMS OF ABUSE.

Meg: your questions answered, one by one:

Eve teasing, yes I see I should have explained more. I like your take very much and you are absolutely correct. The origins of these word is not well explained but it came into common use by the police and media in the 1960s (Giriraj Shah 1993: 233). It is a strange term for the Indian media to adopt given it evokes the Christian concept of Eve in a country where the majority of people are Hindu (around 80%) and Muslim (13%). Christians are a minority (2%). But this term is also used widely in other South Asian societies, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka (Sheila Mitra-Sakar and P. Partheeban 2011). It is also used in Nepal. I see it as a colonialist term. Geetanjali Gangoli argues its semantic origins are Anglo-Indian, evoking the idea of original sin, where a ‘temptress’ seduces a man into doing something he doesn’t want to do. Gangoli says that by using the term ‘teasing’, ‘it normalises and trivialises the issue’. So your idea about minimising is absolutely what this term is about.

Eve teasing is a blanket term for a range of abuse experienced in public. The media often uses it as a proxy for ‘sexual harassment’ and ‘offensive language and behaviour’ directed towards women (Andreas Sedlatschek 2009). Eve teasing is not effectively legislated so it is not seriously treated as an offense and it’s rarely reported to police. The media and various blogs use the term Eve teasing for everything from being women being wolf-whistled at, having men sit very close and leering over them whilst on public transport, receiving sexual taunts, to having nipples pinched, being grabbed as one is walking down the street, being smacked on their backside, and having men masturbate in front of women in public transport – the list goes on. A study of 10 university campuses in Mumbai by K. Jaishankar, Megha Desai and P. Madhava Soma Sundaram (2008) also includes experiences of stalking as a form of eve teasing. For example, unsolicited phone calls, letters and cyberstalking. (The study also incorporates data from Tamil Nadu State and Tirunelveli.)

Eve stalking is almost institutionalised on public transport. For example, a study of 274 women carried out by Sheila Mitra-Sakar and P. Partheeban (2011) finds that 66% of them have experienced eve teasing on public transport. Eve teasing is such a problem that railway companies have introduced women-only train carriages, which are fairly standard in some of the bigger cities in India. It also occurs when are at movie theatres, at the beach, walking through the park, or anywhere public. Vibhuti Patel (2007) has also studied eve calling under the framework of sexual harassment in workplaces (see also Jyoti Puri: 1999: 94-96).

Research shows that Eve teasing happens to girls at school when they enter puberty, which is where they first learn to expect this type of behaviour. During this time, young girls also develop ambivalence about Eve teasing. Jyoti Puri (1999) has conducted excellent research on this topic. She finds that whilst girls and women don’t like this abuse, they feel they cannot change it so they don’t speak out. Instead, they modify their personal behaviour, dress and routines. Some young girls might feel worried about telling their parents in case their behaviour and clothes are scrutinised. Girls tend to give one another advice and strategies for how to handle Eve teasing.

The ambivalence sets in for some women who don’t like the abuse but who feel it is also a demonstration of how attractive they are. This is not the case for all women – in fact, many women in Puri’s research say they go out of their way not to run into Eve teasing. They try not to walk in certain places at night. They avoid eye contact. A lot of women ignore the harassment and pretend not to hear the taunts or they act as if they don’t care that they’re being grabbed, so as not to incite further attention.

Puri and other researchers find that as women get older, they might begin to show aggression, yelling obscenities or slapping men but this comes from years of frustration and it still requires that women manage the problem alone. Whatever tactics are used, women are left with feelings of humiliation, anger and fear. Mohamed Seedat, Sarah MacKenzie and Dinesh Mohan (2006) find that women feel perpetually ‘defensive’. The simple act of walking in public becomes a high ‘energy event’, which is both physically and psychologically draining, because they are constantly monitoring their body language and trying to stay alert in case of abuse.

You mentioned power and I should have addressed this. I don’t think it’s useful to remove the gender element from this case as Eve teasing is specifically something that is used against women. Vibhuti Patel (2007) finds that the main myths about eve teasing amongst men is that women enjoy it; men see it as harmless flirting; and that they also say that some women are ‘asking for it’ by the way they dress. Then again, women in billowy clothes and modest covering get Eve teased, so clearly we can all see this is a load of crap.

Men don’t think they’re doing anything wrong because they are in a position of privilege and they don’t have to think about how women might be affected by their comments and action. They feel that it is their right to shove their attention and sexual aggression on women. In the blog ‘Known Turf’, Annie Zaidi (2006) gave a gutsy account of how she moved away from feeling that she had to stay quiet and look away from men. She started confronting men when her anger went beyond the tipping point after years of this abuse. She found that the men were always surprised by her anger. The first time Zaidi fought back was when a man accosted her on the street and said ‘How much?’ She tried to walk away, but he followed her and asked again. She punched him. Surprised, he said ‘What did I do?’ In another instance, while she was standing outside a movie theatre, a man kept touching Zaidi and when he didn’t stop, she hit him. Shocked, he said, ‘I didn’t do anything’ but he ended up apologising by saying ‘sorry, sister’. Zaidi gives a long list of advice for how women can avoid men’s unwanted attention. Her post has almost 280 comments, mostly from grateful women who find her account and advice useful.

The fact that women need to seek out strategies from other women speaks to the inadequate formal policing of Eve teasing. Zaidi’s account of the surprise that men get when she fights back is testament to the invisibility of women’s status in the eyes of some Indian men. Zaidi is only seen as a person with feelings when she yells and punches. Her violence shocks the men and demands recognition: only then is she is a ‘sister’, a person worthy of respect. This suggests that, to many men, when women are outside the home, they are not sisters, mothers, wives, or people of status. They are sub-human; other. Zaidi responds with aggression – a stereotypically male response – in order to achieve her status as a person worthy of an apology for sexual misconduct. The tactic has worked for Zaidi but it speaks the dangers that women face in policing their own responses to Eve teasing.

Regarding issues of power and othering: Eve teasing does have some intersections with class and caste. For example, Aruna R (1999) argues that children who live in poor or rural areas are more likely to take long public transport rides to get to school. This means that they may be more at a higher risk of sexual harassment.

Mrinalini Sinha (1999) locates his historical analysis of Indian masculinity with respect to patterns of colonialism. Making reference to Padma Anagol-McGinn’s (1994) work on Eve teasing, Sinha sees that the ‘skewed urbanisation of colonial India’ influences how modern-day masculinity is constructed. From the late 1890s and up to mid-20th Century, the industrialisation of Indian cities meant that many men moved away from their rural families and lived in places where there was a strong gender imbalance. This began the restricting gender hierarchies, to the point where today men feel validated by acting sexually aggressive towards women in public.

Martyn Rogers (2008) has also studied the connection between caste, colonial history, masculinity and eve teasing amongst Tamil university students struggling to compete with upper middle class students. The study was conducted in an inner-city college in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, in South India. Rogers sees that Eve teasing is way to enact Tamil masculinity and to regain some of their status. These young men are attempting to resist a ‘Westernisation’ of their masculinity, even as they attempt to gain a higher level of education.

At the same time, the other research and media reports I’ve cited here and in the main body of my article show that Eve teasing affects women across different areas of Indian society. Obviously being affluent and not having to take public transport would minimise exposure to eve teasing, but it doesn’t irradiate the problem altogether.

For a highly problematic view on Eve teasing and power from the perspective of an Indian man (now living in the USA), read Libran Lover’s blog. He argues that eve teasing is wrong, but that he takes great exception to the idea that Eve teasing is a power issue. Libran Lover says he ‘indulged’ in a little ‘light Eve teasing’ in his youth, but he says that he was not thinking about dominating individual woman. Instead, he feels that Eve teasing is borne out of sexual frustration. Libran Lover says that because most arranged marriages are delayed until a certain age, some men start to develop sexual feelings during their adolescence and early 20s, but they have no one to direct these feelings towards. So, in Libran Lover’s view, up until men marry, they ‘indulge’ in Eve teasing because they don’t know any better. Libran Lover’s views are obviously problematic on several levels. Most obviously, Libran Lover legitimates Eve teasing as a passing fad (which the research shows it is not). Libran Lover’s account also normalises this form of abuse, by depicting women as objects to mediate sexual frustration. I’m glad that Libran Lover wrote this account, however, because this view needs to be unpackaged. You can read it here: http://blog.libranlover.net/2006/03/root-cause-of-eve-teasing-in-india.html#eveteasingprecis

If you read it, let me know what you think!

You asked for a clarification on levels of sexual violence in different countries. This will take a lot of time to pull together, but I can tell you that in conflict-afflicted societies, incidents of rape are very high. For example, it is well documented that the Republic of Congo has a high rate of rape that exceeds that of other nations, but the exact figures are difficult to validate. A study published in June this year in the American Journal of Public Health claimed that over 1,000 women are raped every day and 400,000 women are raped annually in Congo, but the methods were dodgy and the United Nations says the study probably overstates its case. The UN estimates that the rate is closer to 200,000 since 1996, but again, the UN says it might be higher. Mass rapes happen in high numbers in war situations including most recently in Rwanda, Bosnia, the Former Yugoslavia, Sudan and Iraq. It is not poverty per se that causes high rates of sexual violence, I would be careful in how you say that. It is more about the political and legal conditions. ‘Fragile states’ that are not adequately meeting the daily needs of their people are usually not providing a consistent level of security, which includes security from sexual violence.

About how this compares to developed nations – rape figures as I noted in my article are grossly underestimated. Outside conditions of war and political instability, the global comparisons are horrific any where you look. Other than the figures I’ve already quoted in my post above, the highest rates of sexual violence which end in death occur in fragile states that are not ‘free’ and democratic (as defined by the Freedom Report). This includes the war situations stated as well as South Africa, where one woman is killed every 6 hours by an intimate partner. In Guatemala, two women are murdered daily. Ciudad Juárez, Mexico has one of the highest rates of women homicides per capita in the world. The official count is close to 400 women dead since the mid 1990s, but local residents think the figure is closer to 5,000 as these other women have gone missing and their cases are unsolved. In city of around 1.5 million people, this proportion is alarming. I would also note that in the case of Juarez, the violence these women experience is directly connected to the USA’s ‘war on drugs’ as this town is a central point for drug exchanges and there is also a high rate of drug-related murders for men. Additionally, these women are placed in an unsafe situation as they are bussed into secluded industrial areas working on American-owned companies that exploit their labour and take no responsibility for their workers’ safety.

Moreover, the UN reports that out of the 800,000 people trafficked annually, 80% are trafficked for sexual purposes, and 80% of these ‘sex slaves’ are women, many of whom are exploited by sexual tourists and clients from advanced nations. Thinking about global figures (how many people and where and who is worse) is not so useful when you consider the global exploitation of workers and ‘sex slaves’ by advanced states. The UN says that it’s best not to get hung up on numbers when it comes to sexual violence, but rather to tackle the context in which it happens.

As for things being much better in developed nations – given that these nations are not typically in a state of active conflict at home, the rates of violence are surprisingly high. Again, referring beyond the figures I cited above, the UN reports that one-third of women murdered annually in the USA are killed by intimate partners. The National Organisation for women reports that almost 1,200 women were murdered by an intimate partner in the USA, which is an average rate of three women per day. This is obviously higher than the rate for Guatemala. Citing data from 2007, the National Institute of Justice puts the murder of women by an intimate partner at 40–50 percent, which is even higher again. The UN also reports that 83% of American girls aged 12 to 16 experienced some form of sexual harassment in public schools. In the European Union, 40-50 percent of women experience sexual harassment at work.

Interesting you talk about the possible connection between popular culture, violence and sexual assault. I’ve been working on a post on this very topic with respect to pornography and the so-called ‘pornofication’ of popular culture. In brief, I can tell you that the connection between violence on screen and sexual violence in real life is not straight-forward. I think it is more about how norms become established in different social networks. For example, amongst some friendship groups, sexual aggression is part of how men enact masculinity. In other friendship or social circles, this is not okay.

Going back to the Eve teasing – Srividya Ramasubramanian and Mary Beth Oliver (2003) argue against the position I’ve just presented. Their ideas probably align more with what you’re saying. They argue that popular Hindi films have glamorised young men’s expectations of what aggressive sexual attention can do for women. The researchers identify that in Hindi films, acting tough and initially upsetting women by showing them persistent unwelcome attention will eventually win a girl over. This Hindi archetype ‘macho hero’ is how mainstream Indian culture defines masculinity – through aggression, valour and perseverance (see also Swarna Rajagopalan 2005: 46).

Thanks for your questions, they really got me thinking and they’ve helped me crystallise my thinking a bit more. I might end up adding some of these comments to the ‘Read More’ section of the blog or in the main body. I’ll see how I go. Thanks for reading and for your great ideas!

LikeLike

Thank you ZZ for that long and satisfying reply to my questions.

The word ‘Eve-teasing’ is so politically loaded! Its effect is to obscure and render trivial the reality and effects of violence against women. Using an innocuous-sounding word like this to refer to practices from ranging from schoolyard-style flirting to sexual assault makes it almost impossible to have a conversation in which people holding different views can understand each other. In any given conversation the parties can be using the word to refer to quite different things. Arguments against violence can be met with ‘what’s the matter can’t you take a joke?’

I think the way to go with words like this is ALWAYS to qualify them by stating the types of practice you are referring to. That gives everyone the tools they need to get to the point of their disagreements. And dissolves the obscuring fog.

I like the argument from Srividya Ramasubramanian and Mary Beth Oliver. What’s represented as normal cool sexy behaviour in mainstream media encourages young women and young men to learn that the schoolyard-macho end of the Eve-teasing spectrum is just how it’s done in these modern groovy times. And if you don’t like it you’re old fashioned, boring, dowdy etc. Reminds me of the message in the 1970s movie Grease: old-fashioned ‘good girls’ were evil teases, but modern cool-hip-popular-girls have heterosexual penetrative sex. All being defined by, and in terms of the pleasures experienced by, men, and the idea that women might have any view at all beyond wanting to please men just not on the radar (spits with disgust.) The idea that women should be as defined by men is so much part of the air we breathe that it’s hard for young women and young men to comprehend what stepping out of it looks like! As Annie Zaidi’s story shows.

Will read ‘Libran lover’. Thanks for the link.

I still feel that sexualising hierarchy (vs sexualising equality) is a fundamental issue here. As long as degrading someone less powerful than yourself affirms you as a man we are in trouble. I do look forward to your post on ‘pornification’ of popular culture!

Thanks for good work and more please.

LikeLike

Hi Meg,

Thanks again for your take on my latest ramblings! I read your comments and I’ve been thinking them over. The ‘schoolyard teasing’ approach to sexual harassment happens in Australia too, even between grown ups. I want to write more on this, but I need to do a bit more thinking on it. I read some lovely research on the socialisation and informal peer-group policing of heterosexuality between young primarily school kids that suggests this dynamic is learned early. I think we focus culturally more on teenagers but we fail to recognise how early it begins. The whole idea that women should be happy to receive comments, compliments and other forms of attention from men reinforces the notion that women should derive their sense of self and pleasure from men. And if women get annoyed by this attention, or feel uncomfortable about it – well, there’s something wrong with them.

Funny you mention Grease! I love this film – it is a family favourite, but yes I agree absolutely; the whole idea that a lady has to change for a man is beautifully exemplified in that story. To be pedantic, that movie actually shows both Sandy and Danny changing their looks, personality and interests for the other person. It’s just that Danny becomes a conformist geek ‘jock’, which is less sexy than being a bad boy ‘stud’, while Sandy turns into a sexy lady. And in the end, the message of the story is: men only have to change a little and they can change right back, but ladies need to maintain a sexy facade for their man.

I think the relationship between the media and sexual hierarchies is not well understood and that the relationship between media and sexual aggression is less so. I don’t see that these relationships are straightforward. Again, I’m interested in how norms of violence are policed by peer groups and how these informal norms reflect broader structural patterns.

Thanks for reading and for making me think harder – I need it!

LikeLike

Hello Dr Zuleyka Zevallos

First of all let me introduce myself, I am Nabaruna Debbarman,an Indian woman by origin.

The issue that you have researched and written about has always been a burning topic and I cannot be more thankful to you that you have done such a great job in detailing this horrendous act so vividly.

It is unfortunate that we pass through such situation in India almost every day, and today I came across your post totally by chance when out of rage I was browsing for this subject matter online, because in last few days a very shameful act has terribly shaken Northeast India , where a teen age girl has been beaten up by a mob of fifty adult men, many of them educated as well.

As a women I am very thankful to you for taking out your time and good will to discuss this matter as well. Thanks a lot.

Regards

Nabaruna.

LikeLike

Hi Nabaruna,

Thank you for your passionate response, I’m truly touched to have you replied to my post in such a personal way. I feel very humbled to have represented this issue in a way that has helped you think through this important, ongoing social issue.

I presume you must be referring to the incident in Guwahati? Thank you for bringing this to my attention, I had not read about it, but now I see that it has received some media attention. Just this evening I was talking to my male cousins about sexual harrassment, trying to get them to understand what it feels like to have to endure men cat calling or grabbing you on the street, as has happened to me in the past, and how learning to be hyper vigilant as a woman in public should never be normalised in society. I feel for this unfortunate woman in Guwahati and I hope there will be justice. I see three men have been arrested; I hope the rest are brought before the court. Authorities need to better address the fact that Eve teasing is a form of gender violence that leads to other, more physical forms of violence. Look after yourself and thank you for reading my work. Best wishes, Zuleyka.

LikeLike

The United Nations General Assembly defines “violence against women” as “any act of gender based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.” The 1993 Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women noted that this violence could be perpetrated by assailants mainly men, family members and even the “State” itself.

Worldwide governments and organizations actively work to combat violence against women through a variety of programs. A UN resolution designated 25 November to 10 December as International

fortnight for the Elimination of Violence against Women.

The patriarchal structure of society and the accompanying gender discrimination has increased women’s vulnerability to violence and its consequences at every stage of life, from womb to tomb. Although various organizations including women’s groups in India have been articulating and working with various agencies to address this societal malaise the outcomes have been a mixed bag of responses.

The unfortunate Nirbhaya case of Dec 16 2012 brought the grossest form of violence against women once again in the lime light. The Justice Verma committee Report in its aftermath has led to changes in law, even though not to the extent desired by human rights activists and women’s groups. The equally horrifying Mathura rape case in the 1980s resulted in changes in law concerning custodial rape.

Unfortunately repeatedly and regularly we still find various cases of violence against women on the

street, at home, and also in the work place reported in media.

LikeLike

Hello Prof. Vibhuti Patel,

Thanks for your detailed comment! It’s true that violence against women is an ongoing issue in India as it is in other countries, but this does not mean this violence has to continue. Other countries have addressed gender violence and reduced its occurrence, so it is worthwhile continuing to advocate for change. Thanks for reading and for sharing your thoughts! – Zuleyka.

LikeLike