Today, I will reflect on the commenting policy that covers my various blogs and social media. In a nutshell, my policy says: 1) discuss sociology; 2) be polite; 3) stay on topic; and 4) be aware of your own bias. I rarely acknowledge individual abuse that comes my way and I delete the majority of abusive comments I receive on my blog, and I block and report abuse on my social media. Periodically, I will discuss broad patterns of these comments on Twitter, using the hashtag #SocModeration (standing for ‘sociology moderation’). This allows me to reflect on the personal costs of what it means for me, a minority woman, to battle racism and sexism online while writing about the sociology of inequality. At the same time, not publishing abuse on my actual blog keeps my ‘home’ welcoming for my key audience: primarily other women of colour and anyone else who respects minorities.

People who come to my blogs to hurl abuse see sexism and racism as insults and as subjective ideas that can be rejected. I discuss how the concept of White male privilege dislocates this individual perspective on discrimination. I end by arguing that, despite the problems I face, public outreach is important. It’s something that sociologists and other scientists can be, and should be, battling together.

We don’t condone interpersonal violence face to face. We can’t be complicit on this culture online. The scientific community needs to take a collective stance against silencing minorities and White women from participating in public discussions. Let’s not allow the normalisation of abuse online. People who are already underrepresented should not expect to be subject to harassment simply because we write about inequality. We should expect to feel safe in leading public debates on education, science and social justice.

Moderation

Most of my writing is on race and gender inequality. I invariably get random comments from the public on my blogs saying that I’m racist for writing about racism or sexist for writing about gender inequality. I’m also treated to a host of expletives or pseudo intellectual insults. Once a man who wrote me a long essay saying that evolution shows women have smaller intellectual capacity than men so my arguments were invalid. That was in response to a post I wrote about the gender symbolism of the Sistine Chapel. Most recently someone called me a racist idiot for an old post I wrote about the social construction of race in anime cartoons.

I never allow hate speech on my blogs, so I don’t allow these tirades to be printed on my social media. But trust me, I report them when I can and they are there for me to see in the back-end of my blogs: long, defensive, angry and gross comments that never engage with the content of what I’ve written, nor the scientific evidence I present.

Notice that my posts are never about calling individuals racist/sexist. They’re not opinion pieces. My posts focus on scientific research of societal processes and social issues. Women sometimes disagree with my posts, which is fine – disagreement is not the same as personal attacks. The vitriolic and belligerent comments saying I’m racist/sexist are, primarily, from men representing White male privilege.

White Male Privilege

Both racism and sexism describe discourses and practices that maintain sexist, racist, cisgender, ableist and heterosexist balance of power society. This includes everything from everyday interactions, to the social organisation of society. White men’s socialisation teaches them to think that their life experiences are the default universal position.

American sociologist Peggy McIntosh describes white privilege as an “invisible knapsack” or a special bag of benefits that White people (of all genders) can take for granted as they go about their daily lives without harassment, fear, stigma or discrimination due to their race. This includes:

- Being able to hang out with people of the same race and gender in all social contexts, including while at work.

- Having access to affordable housing in a neighbourhood where neighbours will be “neutral or pleasant.”

- Being able to shop and travel in public places without being followed.

- Finding people from the same race in the news and media in a range of roles, and not just tainted with criminal overtones.

- Dressing and behaving however one pleases without these choices being seen as a reflection of one’s racial and gender group.

- Speaking to people in authority positions (such as police, teachers and employers) who are of the same race and gender.

White male privilege is not negated by the personal hardships that individual White men face. Everyone has personal problems. Individual men often balk at this idea. They don’t see that they have any special benefits. Subjective views on inequality do not negate that society is structured in a way that benefits some groups over others. Some men get angry thinking that this concept says all men are evil or that they are sexist or racist. Again, this is not about how you see yourself as a person; it is about the social processes that support inequality. White male privilege ensures that the taken for granted benefits of gender and race don’t result in wider discrimination.

Consequences of racism and sexism

Racism and sexism describe systems of institutional oppression. These concepts refer to the inequity and life chances that stem from racial and gender relations. These are not insults to be flung at someone who is analysing social inequality. For example, using racism as an insult takes an individual perspective on institutional oppression. It turns racism into the property of individuals that may be subjectively defended (“I don’t think this is racist!”). It therefore denies the social processes that support discrimination at work, school, the criminal justice system, in public spaces and in private life.

The decision to publish about racism, sexism and other forms of social injustice may not be surprising given I’m a sociologist. I have researched and published on these issues. I have taught these subjects at university. I have also conducted research on these matters for social policy when I worked in public service. Yet most of this work was for “internal” audiences, in the case of academia, and for semi-public policy audiences. Until I increased my social media, my academic papers were sitting behind a paywall or delivered at academic conferences. I’m glad more of my work is public now. Yet publishing on these issues for public audiences, via my blogs and social media, has come at a price. I am expected to put up with public abuse.

The Personal Costs of Harassment

I identify as a woman of colour, and more specifically as a migrant-Australian and Latin-Australian woman. The abuse I face publishing about these issues for public audiences carries an additional personal weight, as this abuse echoes the discrimination I have faced throughout my life. Racism and sexism happens in academia and in public service, but it is not expected, condoned or thought of as just “part of the job.” The law is explicit: I shouldn’t go to work expecting abuse. (Fighting workplace discrimination and harassment at work is another matter.)

Just as it’s unacceptable to allow racism, sexism and other hate speech for any public or private interaction, it is not okay to normalise this discrimination as part of blogging, social media and other public science outreach.

While in the past I deliberated leaving abusive comments on my blogs to show the belligerence of those people, I reflected on the impact of engaging with this abuse. Not only does it come at a personal cost to me, it only incites the abuser to continue thinking it’s okay to keep hurling insults. They aren’t there to engage with my arguments by reflecting on the research I present. They are there to hurt me and to try to silence me into not speaking out on these issues. They bank on other high-profile cases of women who have been abused (e.g. Anita Sarkeesian) or otherwise bullied out of public engagement.

Ultimately, I don’t allow these posts because these people want to use me to amplify their social privilege. My writing angers them because they don’t like having their social position questioned. The very fact that sociology threatens their privilege shows that sociological practices of women of colour (and in other sciences) are important to undoing White male privilege.

Keeping this sociology behind closed doors of academia is a disservice. There are important voices in public sociology, such as Dr Tressie McMillan Cottom, but we need more women of colour sociologists to shift public debates. I’ve tried to encourage other Australian sociologists to join me on social media but they say they are scared of having to face abuse. It’s certainly not pleasant. But writing about sociology for public consumption helps to break down the normalcy of sexism and racism. Talking about how to better manage this abuse is important. Abuse has real consequences. For me, I’ve had to manage how I feel about reading comments that remind me of the abuse and social exclusion I’ve faced my entire life.

In other cases, the threat is more immediate. In a recent example, Dr V, a transgender woman inventor, was ‘outed’ by a journalist and she died by suicide as a result. In another example, Dr Isis, an anonymous science blogger, was identified by Henry Gee, a senior male publisher on the high-profile Nature magazine. Isis writes:

I have undoubtedly been vocal over the last four years of the fact that I believe Nature, the flagship of our profession, does not have a strong track record of treating women fairly. I believe that Henry Gee, a representative of the journal, is responsible for some of that culture. That’s not “vitriolic” and it’s not “bullying”. That is me saying, as a woman, that there is something wrong with how this journal and its editors engage 50% of the population (or 20% of scientists) and I believe in my right to say “this is not ‘ok’.” Henry Gee responded by skywriting my real name because he believed that would hurt me personally – my career, my safety, my family. [My emphasis]

The connection I see between these cases is about gender violence: if you threaten or deny the requests of privileged men, they will use social media to destroy your personal life. There are therefore major issues of privacy and safety for women on social media.

Moving Forward

The idea that we should refrain from doing public science because of the threat of abuse is a public problem that requires collective action.

I hope that more sociologists will join the public sociology effort. We have voluminous papers on how to do public sociology and not enough of us doing it in Australia on social media. The abuse is something we can collective address and support one another on. The questions we should collaborate on include:

- How can we help increase women’ safety online?

- How can we pool together our efforts? How can our discipline better support us?

- How can we contribute to cross-disciplinary action?

If you have ideas on these questions or other thoughts, please share these below!

NEW: Check out my resource to address public harassment of scholars.

Intersectionalism. Even sociologists have trouble dealing with it.

LikeLike

Daniel Taylor Intersectionalism evolved as a theory for the very reasons I’ve discussed. Sociology was once dominated by white male privilege. Then feminism introduced gender inequality as a central issue, but they were mostly white, affluent and Western. Black studies, queer studies, Indigenous and other minority researchers introduced the idea of intersecting inequalities to address the issues I’m talking about here.

LikeLike

It’s a lot easier to talk about it if you don’t exclude people who look wrong from the conversation up front.

Just saying.

LikeLike

I think I might get the point, but I’m an unusual case. For a lot of people the negative emotion will just be used as justification for their own actions.

It isn’t a rational thing, it’s a rationalizing thing.

LikeLike

I don’t understand your comment Daniel Taylor Who looks wrong from your perspective?

LikeLike

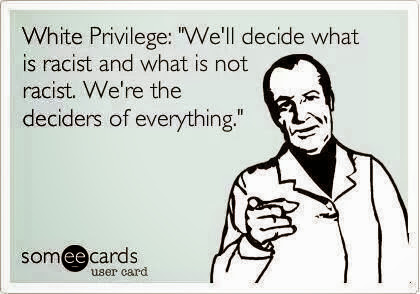

The picture you attached says that I look wrong to be participating in a discussion of inequality.

(So does a fair amount of the included text)

White Male privilege is a localized thing, and not the universal it is frequently branded as being. People will hunt for ways to exclude other people.

LikeLike

Great post. Thanks Zuleyka Zevallos. Sociology is fascinating.

LikeLike

Daniel Taylor The picture is a depiction of what White Male Privilege is about. It matches up with my discussion of this concept in that individual ideas of what sexism and racism is – or isn’t – aren’t correct. People who espouse White male privilege in their arguments against racism and sexism think that they have a right to tell Others what racism and sexism is. They use it to say “That wasn’t racist!” Or “You’re being too sensitive!”

Racism and sexism aren’t subjective. These ideas describe societal processes. It’s about how individual abuse and harassment of women and minorities have other consequences at work, at school and in other ways. I’ve stated that all White men have White Male Privilege even if they don’t think that’s the case. White men have problems – we all do. White men who are working class or less educated have less opportunities than White men who are upper class and well educated. I’m slowly going to start writing on various sociological subjects and this will be one of them.

Nevertheless, there are overall benefits with being a White man that don’t exist in the same way for women and minorities. I’ve given examples of how this works in my post.

You’re right that some men who are angry and abusive towards women and minorities may not agree with me. That’s the point of my post: they come to my personal place on the internet – my blogs – to tell me I’m wrong and to hurl abuse. But that’s the point behind the concept of White male privilege. It benefits them, so they feel entitled to their anger and violent retaliations.

At the same time, I also said that the idea of White male privilege doesn’t make all white men racist or sexist. I’ve stated that combating inequality is a collective effort. This means that if you’re here in solidarity, to stand against social injustice against women and minorities, then you are most welcome to join the discussion!

LikeLike

Sean Kinney Thanks very much for your comment!

LikeLike

So, are you saying I’m being too sensitive?

(Thanks for the explicit welcome, I understand that you aren’t trying to be exclusive)

I’m not saying WMP doesn’t exist, it most definitely does, and I live right smack-dab in the heart of an area where it is alive and well. This makes my life easier in a thousand ways.

But I am also acutely aware that it is not a universal, and that having the wrong religion, or the wrong sexual preference, can chuck it right out the window even where it does dominate.

This isn’t a matter of personal hardships. It is a matter of what a person is, just as much as the color of their skin of what chromosomes they were born with.

LikeLike

Of course, only a few hours later I run into an article that illustrates my point to a ‘T’: https://www.aclu.org/blog/religion-belief/if-you-want-fit-public-school-just-become-christian

LikeLike

Daniel Taylor We’re going around in circles here. My post is about racism and sexism in relation to blogging. I have defined White Male Privilege as a form of social privilege and given links where you can learn more on these concepts. I mentioned that other privileges come into play, including class and heterosexism (the presumption that heterosexuality is the norm). I also used an example of transgender to highlight my argument about the need to create a safe online culture for minorities and women.

The article you link to is not related to this thread. The situation described is awful as this Buddhist child appears to have been bullied in a public school because their teachers were pushing fundamentalist Christianity. This individual case of religious exclusion does not negate the institutional disadvantages of racism and sexism. Whiteness, the element of race in White Male Privilege, does not become erased because you have an specific example of another form of social exclusion. You are still viewing this issue on individual terms, which is the express opposite of the argument I present, which I back up with science in the links provided.

The concepts I’ve presented are not subjective. They are backed up by scientific research. If you’re serious about learning more, you might like to read my preivous post on how personal beliefs, values and attitudes shape how the public understands science. https://plus.google.com/u/0/110756968351492254645/posts/JtJ4AvY49YA

LikeLike

They are not subjecive, and they are particular to a specific environment.

Outside the Internet, there are plentiful exceptions. Even on the Internet, nobody knows what you are, just what you present. So anyone can pass for something they were not born to be if they simply learn to present the proper shibboleths.

LikeLike

It is great you work so hard to share high quality content like this. Thank you for the well written post 🙂

Another cost that has not received nearly enough attention or study is the health consequences. There are multiple likely mechanisms of this including behavioral pathways (e.g., exercise or diet), societal (e.g., health care access as well as quality of health care provided), and psychological/physiological (e.g., chronic stress, experiences of discrimination, which have detrimental health effects via physiological stress reactivity).

You might be interested in a special issue in the Journal of Behavioral Medicine a few years ago with a lot of excellent articles:

http://link.springer.com/journal/10865/32/1/page/1

LikeLike

Thanks for the kind words Joshua Wiley Yes, totally agree with you on the health consequences! I like that you’ve broken this down to behaviour, psychological and social effects.

Studies amongst first-generation migrants show that there is much distrust of the health system amongst some new migrant groups, which is in part a response to the racism and stigma they experience by the Anglo-majority (http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01459740306767#.UuyVA_mSz2M). Health outcomes are better amongst second-generation migrant youth, but it depends on how well-established their communities are in Australia (c.f. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1467-9566.2003.00373.x/full).

I did a study looking at the connection between racism, social integration and resettlement amongst refugees in Australia. I focused on the impact on mental health in particular. I haven’t published this externally (but hope to later this year). The main thing I highlighted was how the process of migration impacted on health and coping mechanisms in Australia. That is, we need to be aware of what refugees go through in their home countries (what was the nature of the conflict that forced them to leave and what trauma/persecution did they experience), what happened to them in transit (including spending time in refugee camps, which has a negative impact on wellbeing), and how social relations and social support when they get here lead to divergent health outcomes.

Farida Fozdar’s work in WA has been really useful to me. She finds that groups from different African nations have unique health problems linked to the trauma of migration. If they were treated poorly by their Government overseas, they already distrust medical professionals. Couple this with racism in Australia and cultural norms that discourage people from seeking help outside the family, and their health-seeking behaviour in Australia is even more jeopardised (http://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/10919/1/africancommunity.pdf).

Thanks so much for this link – the papers look terrific so I will definitely follow them up!

LikeLike

This is a bit of a coincidence, i read this and now see this ‘White Privilege Conference’ is to be held here.

http://www.whiteprivilegeconference.com

LikeLike

This conference is interesting, Joey Brockert. Thanks for sharing. I’m intrigued by the idea of hosting an entire conference on one single concept rather than the broader field of study of Whiteness.

There have been a few great studies in this area, but none that I can recall in more recent years. Reading about this conference, I wonder: could the field possibly be waning in popularity/application in favour of a concept?

The concept of White privilege has remained popular, possibly because the words themselves convey a clear (though confronting) idea: being White gives people special privileges.

Many years a go, I taught a course on race and culture. The single concept that the White/Anglo students had a problem with was Whiteness. They could understand racism and race – but only when it applied to Others; to minorities. But they did not understand concretely how Whiteness works as a culture. This is because Whiteness is both central, ubiquitous and invisible. It’s the norm and so it’s taken for granted.

Maybe the idea of White privilege cuts the larger idea of Whiteness down into something solid that people can better understand. If that’s the case, I want to understand this better.

I would like Whiteness studies to continue as a field because it is more than just everyday privileges. It is about how dominant cultures work and other institutional issues of power. One conference doesn’t necessarily spell the end of another field of study but I am intrigued about this trend.

Thanks for spiking my curiosity!

LikeLike

In reading an article about one fellow’s fight with racism, I realized that we are talking about a coin – one side is racism, the other, white privilege. Mostly this is about raising consciousness, realizing that there are two sides to the coin, which is a lot of what feminism is about, as well as black power here in USA.

LikeLike

Absolutely Joey Brockert White privilege sustains racist ideologies and practices. At the heart of all oppression, whether it’s racial, gender, sexual, class or otherwise, are relations of power. Some groups have more power than others, and elites have even more power over everybody else.

LikeLike

I’m a white male, but I strongly believe that eliminating white male privilege is in my own best interest. The problem is, although I have never got into any debates with anyone about this topic, if I did I wouldn’t know how to convince any other white males that eliminating their privileged status is in their own best interest.

The first thing to do is convince them that they do have privilege, it is the status quo, and it does result in societal problems. I suppose that is the hard part. But then you also need to convincing them that the resultant societal problems have any direct negative impact on them. It might be helpful if sociologists focused more on educating people in this way, in terms of “in your own best interest.”

(This is a copy of my own comment from a re-share of this post: https://plus.google.com/+EarlMatthews/posts/Si8frghtbnc

LikeLike

Hi Ramin Honary Thanks for resharing your comment here! This is a useful discussion: how does eliminating White male privilege benefit White men. You’re right that the message needs to be tailored to different audiences. I’ve been thinking about, and working on, how to address different forms of privilege for people who are not social scientists. Focusing on how privilege creates problems for broader society as well as how it limits the experiences of dominant groups is very important. Over the next day or so, I’ll repost a conversation on how men can help support women in science. It’s not specifically addressing White male privilege, but rather more generally issues of gender inequality. We do touch on diversity. I’ll CC you on the post in case you’re interested.

LikeLike

The Other Sociologist thank you!

LikeLike