Australia is home to the oldest continuous culture in the world, that of Indigenous Australians, and our society also houses one of the highest migrant populations in the world. Australia encompasses over 300 migrant ancestries, with migrants and their children making up half of our population. I’ve just launched a new video series called Vibrant Lives, which explores some of these diverse cultures and the various meanings of multiculturalism in Australia. I’ll focus on different minority groups, as well as covering community events, religious festivals, art exhibitions and community organisations around Melbourne. This post provides some sociological context for my first video on migrant-Australians.

Brief History on Immigration

Australian immigration history is complex and ever-evolving. It begins with the dispossession of Indigenous Australians in 1788, with the arrival of British settlers. They declared Australia to be terra nullius, land belonging to no one, and then decimated the Indigenous population and controlling the remainder through violence and exclusionary policies.

Australia was first used as a place to resettle convicts from England, but from the time of Federation in 1901 to the early 20th Century, immigration was tightly restricted. Amongst the first federation laws passed was the restriction of immigration, first targeting Pacific Islanders, and then more broadly all non-British groups. Afghan Cameleers, Chinese gold miners and various other groups gained entry to Australia at various points to support the expansion of the colony and the economy. These workers were largely exploited and faced intense racism, social exclusion and poor health. In 1919, Prime Minister William Morris Hughes said our discriminatory immigration policy was “The greatest thing we have achieved” as a newly formed colonial nation.

Up until the early 1940s, Australia maintained a strict immigration policy that largely restricted the groups that were allowed entry into Australia. At that stage, the biggest waves of migrants had come disproportionately from English-speaking countries, namely Britain, as these migrants were favoured over non-English speaking migrants. Migrants with darker complexions were screened out from applying for entry with an unfair written exam given to them in a language other than English and not in their native tongue. This became colloquially known as the “White Australia Policy,” a term encapsulating Australia’s racist immigration policies.

During the Second World War, the Australian government allowed asylum to Jewish refugees from various nations, in the first mass-immigration program following British colonisation. Other refugee groups also gained entry, such as a small group of Japanese asylum seekers. In the post-War period, Australia would go on to revolutionise its immigration stance; firstly, by allowing greater numbers of Western Europeans into the country, and eventually by encouraging migrants from Southern Europe, with a preference for lighter-skinned workers. Our immigration policies remained committed to racist ideals, but economic demands for cheap labour motivated an increase in foreign workers.

The so-called White Australia policy began to be softened in 1966, with a greater number of migrant workers allowed entry, and citizenship granted to migrants who had been in Australia for at least 15 years. Up to this point, migrants were expected to assimilate to Australian culture, and lose as much of their cultural practices as possible. From 1973 to 1975, Australia officially moved from its race-discrimination stance and assimilation policies to a non-discriminatory immigration policy. Migrants could now become migrants after three years, and the government started to invest more resources into research and social services to support our new official policy of multiculturalism – the respect of cultural diversity and social inclusion of migrants.

From the mid-1970s and early 1980s, Australia’s immigration intake has included refugee groups from various parts of South-East Asia, Central and South America, and the Middle East. Our family reunion and skilled migration programmes have brought in migrants from all over the world, particularly from China and India. From the 1990s to the present day, response to ongoing civil conflict led to a widening intake of migrants and asylum seekers from African and Middle Eastern nations. As a result of Australia’s changing immigration intake, Australia’s population has diversified considerably.

Demographics of Australian-Migrants

The first national Australian Census of 1911 recorded that the biggest overseas groups in Australia were English, Irish and Scottish. From 1947 to 2004, over six million migrants arrived in Australia. The overseas-born population has grown from 10 percent in the post-War period to to 27 percent in the most recent Census of 2011. Over 6.2 million Australians were born overseas. People from the United Kingdom make up our biggest migrant group. They represent over 5% of Australia’s population. By 2014, the other relatively larger migrant groups include New Zealand (2.6%), China (1.9%), India (1.7%), the Philippines (1.0%) and Vietnam (1.0%) (see image further below).

European groups such as from Italy and Germany have been in Australia longer, and as a result they have an older age structure, with a median age over 60 years. This is up to twice the age of relatively newly arrived groups such as from India.

Australians belong to over 300 ancestries. Generational trends highlight that our nation’s diverse origins are much bigger than we might expect. Over a quarter of Australia’s population are first-generation migrants (people born overseas). Alternatively, they are known as first-generation Australians. Amongst the biggest ancestry groups, at least three quarters of Indian (80%) and Chinese people (74%) are in the first-generation. Only around a third of Dutch and Greek Australians are first-generation, only one quarter of Italians and less than one fifth of Anglo-Celtic groups are the same. People who claim an Irish ancestry are the least likely to be in the first-generation (13%).

Additionally, there are 4.1 million second-generation Australians who represent 20% of the nation. They are counted in the Census as an Australia-born person who has at least one parent born overseas. The biggest second-generation groups are European, including Greek (45% of ancestry group), Dutch (43%), and Italian (41%). Only around one fifth of Anglo-Celtic, Chinese and Indian Australians are in the second-generation.

Altogether, this means that half of Australia’s total population is either a migrant or the child of a migrant.

Around 10.6 million people, or 53% of Australians, are classified as third-generation or beyond. This refers to Australia-born people with both parents born in Australia. The biggest ancestry cited is Australian, while most of the other groups are predominantly Anglo-Celtic. This includes Irish, Scottish, and English, with two-thirds to three-quarters of people reporting these ancestries being in the third-generation. Germans also have a large proportion of people in the third-generation (63%). In comparison, other European groups have only one quarter to one third of people in the third-generation. Only a minority of Chinese (4.4%) and Indian (1.6%) Australians are in the third-generation.

The Census includes Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the third-generation (670,000 people or 3% of the nation), although they are the only non-migrant group in Australia, as they are the Traditional Owners of Australia.

Most Australians speak only at home (81%), but other major languages include Mandarin (1.7%); Italian (1.5%), Arabic (1.4%), Cantonese (1.3%), and Greek (1.3%).

The median length of residence for first-generation migrants is 20 years. This ranges from a median of 40 years for most European groups, to only 10 years for most Asian groups. Migrants live largely major cities, predominantly Sydney (39%); Melbourne (35%), and Perth (37%). The biggest proportion of urban dwellers include people from Somalia, Lebanon, and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Groups from Asia and Southern Europe are also predominantly settled in urban areas, while Anglo-Celtic and Western Europeans are more spread out. This includes migrants from New Zealand, the UK, Germany and the Netherlands who live in outer metropolitan and regional areas.

Despite their cultural and linguistic differences, most migrants feel Australian. Even though up to 40% of migrants face racism, the overwhelming majority of migrants say that Australia’s multiculturalism is good for the nation, and that it’s important to their sense of national belonging.

https://plus.google.com/110211166837239446186/posts/U8iYu57Wn4t

International Perspective

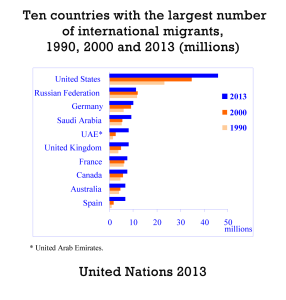

Since the beginning of this century, Australia sustained the ninth largest overseas-born population in the world, following nations such as the United States, Russia, Germany, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. Australia also has the eleventh largest proportion of its national population born overseas. Australia is known as one of four “Traditional Immigration Nations,” along with Canada, the USA and New Zealand. We have an higher proportion of overseas-born people than the other Traditional Immigration Nations. We also have the fourth-highest overseas-born population amongst OECD nations.

Vibrant Lives

Since the late 1970s, Australian law has recognised the right for migrants to maintain their cultures free from discrimination, and to have their social, cultural and historic contributions to the nation recognised. There is much to celebrate about Australian multiculturalism, but also much that requires change. My research shows that Australian multiculturalism is a source of strength to migrants, who often feel excluded by Anglo-Australians. Other research comes to similar conclusions. A national survey by Professor Ien Ang finds that, while Anglo-Australians feel free to dip into certain aspects of minority cultures that they enjoy (such as music or food), they are uneasy about embracing these cultures as part of our core national culture. Migrants who are not Anglo-Celtic feel that they do not see enough of themselves in mainstream portrayals of what it means to be Australian.

Racism remains an ongoing problem, not just for migrants, but also acutely for Indigenous Australians. Additionally, our social policies on refugees have worsened to the point of callous exclusion. In later posts and videos, I’ll explore these themes further.

My Vibrant Lives video series will look at multiculturalism from a sociological perspective. I’ll provide demographic profiles of different migrant and Indigenous Australian groups and discuss community events in the city of Melbourne. As a migrant-Australian sociologist (first-generation Latin-Australian), I want to create videos that are informative and shed light on minority cultures that otherwise receive little media and public attention. I’ll talk with community organisations about their advocacy and efforts to expand social inclusion. I’ll also be interviewing artists, researchers and other community leaders, as well as making other videos about Australian sociology.

You can subscribe to my YouTube channel to get notifications on my videos or to have them delivered to your inbox. Follow me on Instagram @OtherSociology to get updates on my series using the tag #VibrantLives

Here’s a taste of upcoming videos!

http://instagram.com/p/zEisKZG-1f/?modal=true

http://instagram.com/p/um5Ze0G-75/?modal=true

http://instagram.com/p/umZ-RQG-zS/?modal=true

http://instagram.com/p/uCkajFm-7i/?modal=true

http://instagram.com/p/thhNO2m-2l/?modal=true

http://instagram.com/p/nxXsdrm-15/?modal=true

http://instagram.com/p/gxFi50G-zU/?modal=true

Connect With Me

Follow me @OtherSociology or click below!

This is really great and more reporting on multiculturalism is a huge plus to the community. Australia can be so myopic at times.

LikeLike

Thanks very much for your comment Sean Howell! Australian multiculturalism is one the truly unique and wonderful features of Australia, and you’re absolutely right, this doesn’t always get much focus.

LikeLike

Well done

LikeLike