This page is a resource explaining general sociological concepts of sex and gender. The examples I cover are focused on experiences of otherness.

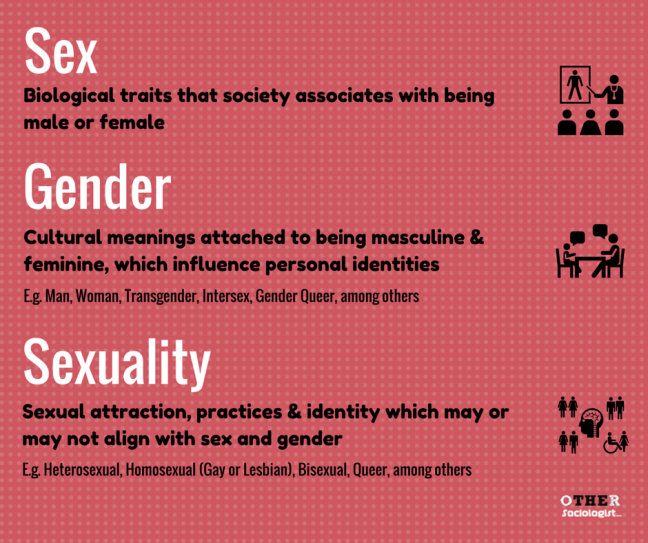

In sociology, we make a distinction between sex and gender. Sex are the biological traits that societies use to assign people into the category of either male or female, whether it be through a focus on chromosomes, genitalia or some other physical ascription. When people talk about the differences between men and women they are often drawing on sex – on rigid ideas of biology – rather than gender, which is an understanding of how society shapes our understanding of those biological categories.

Gender is more fluid – it may or may not depend upon biological traits. More specifically, it is a concept that describes how societies determine and manage sex categories; the cultural meanings attached to men and women’s roles; and how individuals understand their identities including, but not limited to, being a man, woman, transgender, intersex, gender queer and other gender positions. Gender involves social norms, attitudes and activities that society deems more appropriate for one sex over another. Gender is also determined by what an individual feels and does.

The sociology of gender examines how society influences our understandings and perception of differences between masculinity (what society deems appropriate behaviour for a “man”) and femininity (what society deems appropriate behaviour for a “woman”). We examine how this, in turn, influences identity and social practices. We pay special focus on the power relationships that follow from the established gender order in a given society, as well as how this changes over time.

Sex and gender do not always align. Cis-gender describes people whose biological body they were born into matches their personal gender identity. This experience is distinct from being transgender, which is where one’s biological sex does not align with their gender identity. Transgender people will undergo a gender transition that may involve changing their dress and self-presentation (such as a name change). Transgender people may undergo hormone therapy to facilitate this process, but not all transgender people will undertake surgery. Intersexuality describes variations on sex definitions related to ambiguous genitalia, gonads, sex organs, chromosomes or hormones. Transgender and intersexuality are gender categories, not sexualities. Transgender and intersexual people have varied sexual practices, attractions and identities as do cis-gender people.

People can also be gender queer, by either drawing on several gender positions or otherwise not identifying with any specific gender (nonbinary); or they may move across genders (gender fluid); or they may reject gender categories altogether (agender). The third gender is often used by social scientists to describe cultures that accept non-binary gender positions (see the Two Spirit people below).

Sexuality is different again; it is about sexual attraction, sexual practices and identity. Just as sex and gender don’t always align, neither does gender and sexuality. People can identify along a wide spectrum of sexualities from heterosexual, to gay or lesbian, to bisexual, to queer, and so on. Asexuality is a term used when individuals do not feel sexual attraction. Some asexual people might still form romantic relationships without sexual contact.

Regardless of sexual experience, sexual desire and behaviours can change over time, and sexual identities may or may not shift as a result.

Gender and sexuality are not just personal identities; they are social identities. They arise from our relationships to other people, and they depend upon social interaction and social recognition. As such, they influence how we understand ourselves in relation to others.

Gender

The definition of sex (the categories of man versus woman) as we know them today comes from the advent of modernity. With the rise of industrialisation came better technologies and faster modes of travel and communication. This assisted the rapid diffusion of ideas across the medical world.

Sex roles describes the tasks and functions perceived to be ideally suited to masculinity versus femininity. Sex roles have converged across many (though not all) cultures due to colonial practices and also due to industrialisation.

For example, in early-2014, India legally recognised the hijra, the traditional third gender who had been previously accepted prior to colonialism.

Sex roles were different prior to the industrial revolution, when men and women worked alongside one another on farms, doing similar tasks. Entrenched gender inequality is a product of modernity. It’s not that inequality did not exist before, it’s that inequality within the home in relation to family life was not as pronounced.

In the 19th Century, biomedical science largely converged around Western European practices and ideas. Biological definitions of the body arose where they did not exist before, drawing on Victorian values. The essentialist ideas that people attach to man and woman exist only because of this cultural history. This includes the erroneous ideas that sex:

- Is pre-determined in the womb;

- Defined by anatomy which in turn determines sexual identity and desire;

- Differences are all connected to reproductive functions;

- Identities are immutable; and that

- Deviations from dominant ideas of male/female must be “unnatural.”

As I show further below, there is more variation across cultures when it comes to what is considered “normal” for men and women, thus highlighting the ethnocentric basis of sex categories. Ethnocentric ideas define and judge practices according to one’s own culture, rather than understanding cultural practices vary and should be viewed by local standards.

Social Construction of Gender

Gender, like all social identities, is socially constructed. Social constructionism is one of the key theories sociologists use to put gender into historical and cultural focus. Social constructionism is a social theory about how meaning is created through social interaction – through the things we do and say with other people. This theory shows that gender it is not a fixed or innate fact, but instead it varies across time and place.

Gender norms (the socially acceptable ways of acting out gender) are learned from birth through childhood socialisation. We learn what is expected of our gender from what our parents teach us, as well as what we pick up at school, through religious or cultural teachings, in the media, and various other social institutions.

Gender experiences will evolve over a person’s lifetime. Gender is therefore always in flux. We see this through generational and intergenerational changes within families, as social, legal and technological changes influence social values on gender. Australian sociologist, Professor Raewyn Connell, describes gender as a social structure – a higher order category that society uses to organise itself:

Gender is the structure of social relations that centres on the reproductive arena, and the set of practices (governed by this structure) that bring reproductive distinctions between bodies into social processes. To put it informally, gender concerns the way human society deals with human bodies, and the many consequences of that “deal” in our personal lives and our collective fate.

Like all social identities, gender identities are dialectical: they involve at least two sets of actors referenced against one another: “us” versus “them.” In Western culture, this means “masculine” versus “feminine.” As such, gender is constructed around notions of Otherness: the “masculine” is treated as the default human experience by social norms, the law and other social institutions. Masculinities are rewarded over and above femininities.

Take for example the gender pay gap. Men in general are paid better than women; they enjoy more sexual and social freedom; and they have other benefits that women do not by virtue of their gender. There are variations across race, class, sexuality, and according to disability and other socio-economic measures. See an example of pay disparity at the national level versus race and pay amongst Hollywood stars.

Masculinity

Professor Connell defines masculinity as a broad set of processes which include gender relations and gender practices between men and women and “the effects of these practices in bodily experience, personality and culture.” Connell argues that culture dictates ways of being masculine and “unmasculine.” She argues that there are several masculinities operating within any one cultural context, and some of these masculinities are:

- hegemonic;

- subordinate;

- compliant; and

- marginalised.

In Western societies, gender power is held by White, highly educated, middle-class, able-bodied heterosexual men whose gender represents hegemonic masculinity – the ideal to which other masculinities must interact with, conform to, and challenge. Hegemonic masculinity rests on tacit acceptance. It is not enforced through direct violence; instead, it exists as a cultural “script” that are familiar to us from our socialisation. The hegemonic ideal is exemplified in movies which venerate White heterosexual heroes, as well as in sports, where physical prowess is given special cultural interest and authority.

A 2014 event between the Australian and New Zealand rugby teams shows that racism, culture, history and power complicate how hegemonic masculinities play out and subsequently understood.

Masculinities are constructed in relation to existing social hierarchies relating to class, race, age and so on. Hegemonic masculinities rest upon social context, and so they reflect the social inequalities of the cultures they embody.

Similarly, counter-hegemonic masculinities signify a contest of power between different types of masculinities. As Connell argues:

“The terms “masculine” and “feminine” point beyond categorical sex difference to the ways men differ among themselves, and women differ among themselves, in matters of gender.”

Sociologist CJ Pascoe finds that young working-class American boys police masculinity through jokes exemplified by the phrase, “Dude, you’re a fag.” Boys are called “fags” (derogative word for homosexual) not because they are gay, but when they engage in behaviour outside the gender norm (“un-masculine”). This includes dancing; taking “too much” care with their appearance; being too expressive with their emotions; or being perceived as incompetent. Being gay was more acceptable than being a man who did not fit with the hegemonic ideal – but being gay and “unmasculine” was completely unacceptable. One of the gay boys in Pascoe’s study was bullied so much for his dancing and clothing (wearing “women’s clothes”) that he was eventually forced to drop out of school. The school’s poor management of this incident is an unfortunately all-too-common example of how everyday policing of gender between peers and inequality within institutions reinforce one another.

See the video illustrating how hegemonic masculinity is damaging to men. Notice that most of these often-heard sayings directed at boys and men use femininity and heterosexism as insults. (Heterosexism is the presumption that being a certain type of heterosexual person is “natural” and anything else is “not normal.”)

Femininity

Professor Judith Lorber and Susan Farrell argue that the social constructionist perspective on gender explores the taken-for-granted assumptions about what it means to be “male” and “female,” “feminine” and “masculine.” They explain:

women and men are not automatically compared; rather, gender categories (female-male, feminine-masculine, girls-boys, women-men) are analysed to see how different social groups define them, and how they construct and maintain them in everyday life and in major social institutions, such as the family and the economy.

Femininity is constructed through patriarchal ideas. This means that femininity is always set up as inferior to men. As a result, women as a group lack the same level of cultural power as men.

Women do have agency to resist patriarchal ideals. Women can actively challenge gender norms by refusing to let patriarchy define how they portray and reconstruct their femininity. This can be done by rejecting cultural scripts. For example:

- Sexist and racist judgements about women’s sexuality;

- Fighting rape culture and sexual harassment;

- By entering male-dominated fields, such as body-building or science;

- Rejecting unachievable notions of romantic love disseminated in films and novels that turn women into passive subjects; and

- By generally questioning gender norms, such as by speaking out on sexism. Sexist comments are one of the everyday ways in which people police and maintain the existing gender order.

As women do not have cultural power, there is no version of hegemonic femininity to rival hegemonic masculinity. There are, however, dominant ideals of doing femininity, which favour White, heterosexual, middle-class cis-women who are able-bodied. Minority women do not enjoy the same social privileges in comparison.

The popular idea that women do not get ahead because they lack confidence ignores the intersections of inequality. Women are now being told that they should simply “lean in” and ask for more help at work and at home. “Leaning in” is a limited way of overcoming gender inequality only if you’re a White woman already thriving in the corporate world, by fitting in with the existing gender order. Women who want to challenge this masculine logic, even by asking for a pay rise, are impeded from reaching their potential. Indigenous and other women of colour are even more disadvantaged.

https://plus.google.com/110211166837239446186/posts/7Ujcek5Auov

Some White, middle-class, heterosexual cis-women may be better positioned to “lean in,” but minority women with less power are not. They’re fighting sexism and racism and class discrimination all at once.

Cross-national studies show that social policy plays a significant role in minimising gender inequality, especially where publicly funded childcare frees up women to fully participate in paid work. Cultural variations of gender across time and place also demonstrate that gender change is possible.

Transgender and Intersex Australians

Nationally representative figures drawing on random samples do not exist for transgender people in Australia. The Sex in Australia Study organised a sub-set of questions to address transgender or intersex issues, but these were not used as no one in their survey specified that they were part of these groups. The researchers think that transgender and intersex Australians either nominated themselves broadly as woman or men, and as either heterosexual, gay, lesbian, bisexual or asexual. Alternatively, transgender and intersex Australians may have declined to participate in the survey. The researchers note that around one in 1,000 Australians are transgender or intersex. The Private Lives study, which surveyed over 3,800 lesbian, gay, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual (LGBTQIA) Australians finds that 4.4% identify as transgender (and a further 3% prefer another term to describe their sex/gender other than male, female or transgender).

American and British estimates are no more exact. Smaller or specialised surveys on issues such as surveillance and tobacco estimate that between 0.2% and 0.5% of Americans are transgender, while surveys in the UK identify that up to 0.1% of the population has began or undergone gender transition (noting this does not capture other people who may be considering transgender options).

The research shows that transgender people face various gender inequalities. They lack access to adequate healthcare; they are at a high risk of experiencing mental illness as a result of family rejection, bullying and social exclusion; and they face high rates of sexual harassment. They also face much discrimination from doctors, police, and other authority groups. Work colleagues discriminate against transgender people through informal channels, by telling them how to dress and how to act. Employers discriminate in tacit ways, which might manifest as gender bias leading managers to question how gender transition may impact on work productivity. Employers also discriminate in overt ways, by promoting and affirming transgender men only when they conform to hegemonic masculinity ideals, and generally holding back or otherwise punishing transgender women. Feminism has yet to fully embrace transgender inclusion as a feminist cause. Transgender advocacy groups have made great strides to increase visibility and rights of transgender people. Nevertheless, mainstream feminism’s reticence to take up transgender issues serves only to perpetuate gender inequality.

Transgender people have always lived in Australia. Read below to learn more about sistergirls, Aboriginal transgender women, and how Christianity attempted to displace their cultural belonging and femininity.

Intersex people have been, up until recently, heavily defined in popular culture by largely damaging ideas from medical science. Practitioners tend to present intersex conditions through a pathological lens, often leaving individuals and families feeling that they have little choice other than surgical intervention to “correct” gender. Sharon Preves’s research shows that medical interventions often have devastating effects on gender identity and sometimes on sexual function. Girls with an enlarged clitoris and boys with a micro-penis are judged by doctors to have an ambiguous sex and might be operated on early in life. What is meant to be a cosmetic fix to make bodies “normal” can sometimes lead to harmful self-doubt and relationship problems for some intersex people. Others do not experience such trauma, and they feel more supported especially when parents and families are more open to discussing intersexuality rather than hiding the condition. Much like transgender people, intersex people have also been largely ignored by mainstream feminism, which only amplifies their experience of gender inequality.

Gender Across Time and Place

Behaviours that come to be understood as masculine and feminine vary across cultures and they change over time. As such, the way in which we understand gender here and now in the city of Melbourne, Australia, is slightly different to the way in which gender is judged in other parts of Australia, such as in rural Victoria, or in Indigenous cultures in remote regions of Australia, or in Lima, Peru, or Victorian era England, and so on. Still, the notion of difference, of otherness, is central to the social organisation of gender. As Judith Lorber and Susan Farrell argue:

“What stays constant is that women and men have to be distinguishable” (my emphasis).

Gender does not look so familiar when we look at other cultures – including our own cultures, back in time. Here are examples where hegemonic masculinity (issues of gender and power) look very different to what we’ve become accustomed to in Western nations. Let’s start with a historical example from Western culture.

16th Century Europe

European nations have not always adhered to the same ideas about feminine and masculine. As I noted a few years ago, aristocratic men in Europe in the 16th and 17th Centuries wore elaborate high-heeled shoes to demonstrate their wealth. The shoes were impractical and difficult to walk in, but they were both a status symbol as well as a sign of masculinity and power. In Western cultures, women did not begin wearing high-heeled shoes until the mid-19th Century. Their introduction was not about social status or power, but rather it was a symptom of the increasing sexualisation of women with the introduction of cameras.

The cultural variability of how people “do gender” in different parts of the world demonstrates the cultural specificity of gender norms. Gender has different norms at different places at different points in time. The Wodaabe nomads from Niger are a case in point.

Wodaabe (Niger)

Wodaabe men will dress up during a special ceremony in order to attract a wife. They wear make-up to show off their features; they wear their best outfits, adorned with jewellery; and they bare their teeth and dance before the single women in their village. To the Western eye, these men may appear feminine, as Western culture associates make up and ornamental body routines with women. Yet in this pastoral culture, the men’s elaborate make-up, dress and behaviour are a show of virility. The women pick the men according to their costume and dance. This is another custom that is contrary to dominant models of gender in the West, which demand that women be more passive, and wait until a man approaches her for romantic or sexual attention.

There are various other examples of cultures and religions where gender is done in alternative ways which recognise genders beyond the binary of male/female.

“Two Spirit” (Navajo Native American)

I wrote about the “Two Spirit” People found amongst the Navajo Native American cultures, who make up two additional genders: the feminine man (nádleehí) and masculine woman (dilbaa). They are traditionally considered to be sacred beings embodying both the feminine and masculine traits of all their ancestors and nature. They are chosen by their community to represent this tradition, and once this happens, they live out their lives in the opposite gender, and can also get married (to someone of the opposite gender to their adopted gender). These couples have sex together and they may also have sex with other partners of the opposite gender. If they have children, they are accepted into the Two Spirit household without social stigma.

Female Husbands (Various African Cultures)

Over 30 cultures in African regions allow women to marry other women; they are called “female husbands.” Typically they must already be married to a man, and they are almost exclusively wealthy as they need to pay a “bride-price” (as do men who marry women). The women do not have sexual relations, it is more of a family and economic arrangement. (Human rights activists challenge this saying that because homosexuality is shrouded in secrecy, these women may not want to admit to sexual relationships; however, there is no empirical evidence to this effect.)

The Nandi people of Kenya allow this tradition. It is permissible when an older woman has not borne a son, and she will marry a woman to bear her a male heir. The “female husband” will now see herself as a man, and will abscond from feminine duties, such as carrying objects on her head, cooking and cleaning. The female husband takes on male roles, such as entertaining guests while her wife waits on them. The Abagusii people of Western Kenya allow a female husband to take a wife to bear her children, and the biological father has no rights over them. The Lovedu of South Africa and the Igbo of Benin and Nigeria also practice a variation of female husband, where an independently wealthy woman will continue to be a wife to her male husband, but she will set up a separate home for her wife, who will bear her children. These arrangements continue in the present-day and can be ideal for young single mothers who need security.

Amongst the Igbo Land in Southeast Nigeria, both women will continue to have sexual relations with men, however, the female husbands must do this discreetly. If she becomes pregnant, her children are considered “illegitimate” and are treated as outcasts. The children of her wife remain her responsibility and they are not shunned. The female-husband tradition preserves patriarchal structure; without an heir, women cannot inherit land or property from their family, but if her wife bears a son, the female wife is allowed to carry on the family name and pass on inheritance to her sons. Nigerian historian, Dr Kenneth Chukwuemeka Nwoko calls this arrangement a patri-matriarchy. The female husband would be left without status if she fails to produce a male heir, yet once assuming their role as husband, she receives authority over her family.

Kathoey (Thailand)

The Kathoey from Thailand are born biologically male but around half identify as women while the rest identify as “sao praphet song” (“a second kind of woman”). Alternatively, they see themselves as transgender women; and others still see themselves as a “third sex.” Monarchy rule and resistance to external colonialism led to an aggressive modernisation campaign that made traditional Kathoey gender practices more difficult. While Thailand generally has less punitive laws about homosexuality (it is not illegal to be gay), LGBTQIA people do not have the same rights as heterosexual couples, and the Kathoey struggle for social recognition of their gender identity.

Kathoey (Ladyboys) – Documentary from faithjuliana on Vimeo.

While the Kathoey are tied to older gender traditions, Peter Jackson, Professor of Thai culture and history at the Australian National University, argues that present-day identities and activism amongst Kathoey are informed by both modern and global sensibilities that arose after World War II. Kathoey women have become a large tourism attraction which stands at odd with their own legal struggles as well as those of other LGBTQIA people in Thailand. Jackson writes:

“My research on Thai queer genders and sexualities reveals that contemporary patterns of kathoey transgenderism are just as recent and as different from premodern forms as Thai gay sexualities, with Thailand’s kathoey cultures taking their current forms as a result of a 20th century revolution in Thai gender norms… The cultural prominence of gender in Thailand is reflected in the intense popular fascination with the transgender kathoey and the relative invisibility of Thailand’s large population of gender-normative gay men in both local and international media representations of queer Thailand.”

Celebrity Kathoey, Nok, is fighting for legal and medical support of poor and rural transgender women in Thailand. She has a Masters degree and is a successful business woman. She feels lucky to have always had her family’s support, but that did not stop her from being jailed as a youth for carrying fake female identification. She now runs a charity helping underprivileged transgender women gain access to medical treatment to support their gender transition. She is also seeking to challenge the law to recognise transgender people’s gender identity, as official documentation currently forces them to legally identify as their biological sex.

From the Documentary Ladyboys, Episode, “Celebrity Ladyboys.”

Studying Gender Sociologically

We can study how people “do” gender using ethnographic methods, such as fieldwork and observation. If we are interested in understanding how people make sense of their identities, or we want to go in-depth into their gender experiences, we would use other theories or methods, such as qualitative methods, like one-on-one interviews. If we wanted to study direct measures of gender inequality, we might use quantitative methods such as population surveys to cross-reference how people from different genders are paid at work; or we might get people to carry out time-use diaries to collect data about how much housework they do or how much time they spend doing tasks at work relative to their colleagues; and so on.

Mixed methods can be ideal when studying gender inequality. For example, in domestic labour within families, in order to “go beneath the cover story” of domestic equality and domestic labour. This might involve carrying out time use diaries in addition to interviews, or conducting extended interviews with each member of the family to get a holistic picture of how their gender identities, gender practices and family “cover story” diverge.

Learn More

Read more of my research on gender and sexuality.

- Sociology of Sexuality

- ‘That’s My Australian Side’: The Ethnicity, Gender and Sexuality of Young Women of South and Central American Origin, Journal of Sociology 39(1): 81-98.

- ‘A Woman Is Precious”: Constructions of Islamic Sexuality and Femininity of Turkish-Australian Women’, in P. Corrigan, et al. (Eds) New Times, New Worlds, New Ideas: Sociology Today and Tomorrow. Armidale: The Australian Sociological Association and the University of New England.

- My blog posts on Gender & Sexuality

- My blog posts on Gender at Work (on Social Science Insights)

- Follow me on Facebook for short-form discussion of gender and sexuality in the news and pop culture, as well as other issues of intersectionality.

- Circle me on Google+ to get micro-blog posts on gender, intersectionality and otherness.

- Get further analysis and resources from my Pinterest board: Sociology of Gender and Sexuality on Pinterest.

Citation

To cite this article:

Zevallos, Z. (2014) ‘Sociology of Gender,’ The Other Sociologist, 28 November. Online resource: https://othersociologist.com/sociology-of-gender/

Note: This page is a living document, meaning that I will add to it over time.

How does sex/gender and race/ethnicity compare to when it comes to language and reinforced perceptions?

LikeLike

Hi Mary. This sounds like an assignment question, which I don’t answer as per my commenting policy. Rather than ask for the answer, how do you understand this question and what sociological concept would you use to help find an answer? I’d be glad to talk this through with you, but you have to try to find the answer yourself. 🙂

LikeLike

In my opinion, this doesn’t seem like an “assignment question.” Mary seems curious and perhaps she wants to see your point of view.

LikeLike

Hi Christopher. While it’s honourable that you’re defending Mary, a random person on the internet, your passion for the subject matter is clear, given you have come to my blog to demand an answer to someone else’s question from two years ago. I offered to help Mary but she wanted an easy answer for an assignment. My commenting policy is there for a very good reason. It weeds out abusive, tiresome, counter-productive, and repetitive questions. As well as trolls. 😉

LikeLike

I just loved the way you explained how gender is socially constructed. But I wonder, what was the beginning of this social construction. I mean, how did we know and develop the idea that women have to be shy and men should suppress their emotions?

LikeLike

Hi Unmeshdinda,

The stereotypes you’ve described – women should be shy and men suppress emotions – are not universal. These are typical in Western European traditions, but did not always exist. Far from being seen as “shy,” in ancient Greek culture, women were seen as wild and in need of control. In Victorian times, even though high-status women were expected to be more demure, women were still seen to be overtly sexual and wild, which is why women were overly medicated and often prescribed (barbaric) medical interventions. Many cultures around the world encourage men to express their emotions in various ways, especially during special rituals.

So how did these two specific stereotypes rise up? Through Christianity and colonial expansion. Christian tradition has its origins in pagan and other religions. In these religions, women had greater authority and women’s emotions were not policed in the same way we see in modern times. As different Christian traditions gained power, and blended pagan and other cultures with emerging Roman, Greek, British and similar colonial powers over the ages, Christianity took a more strict control of gender as a binary. Christian ideas of gender came to see women as inferior to men. Women’s sexuality was strongly regulated. Men and women’s emotions were set up as a binary, even more so during the Enlightenment period. Masculinity became strongly tied to ideas of Western European ideals of “rationality” and controlled emotions. Women were defined by being the opposite of men.

The way gender is organised today is very different to the ways in which gender was organised in the past. Nothing about gender stereotypes are natural, normal or pre-destined. Gender is constantly changing and it is a product of history, culture and place.

Thanks for your question!

LikeLiked by 2 people

how has social media (if it has) changed the perceptions among the young user of gender?

LikeLike

Hi Namita. Please see my comments policy – I don’t answer homework questions. I get these at least a couple of times every week, along with other requests. If you want to tell me how you understand this question and how you plan to answer it, I’d be happy to comment on your thinking process. 🙂

LikeLike

Hi! How would you cite this article for a report? 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Laura. Sorry I missed this! Reference is: Zevallos, Z. (2014) ‘Sociology of Gender,’ The Other Sociologist, 28 November.

LikeLike

Hi there

On the topic of gender identity, im very curious as to how experiences of sexual trauma affect the development of gender identity. A female friend of mine was raped as a little girl and has spoken about how she subsequently adopted a butch Identity as she felt that being “one of the boys” mitigated her vulnerability. I also see in this a rejection of sexual objectification as traditional femininity usually involves a considerable degree of emphasis upon presenting oneself – either “modestly” or “slutty” – according to the anticipated sexual responses of men. Are there any studies that have been done on a possible link between sexual trauma and rejection of femininity? Thanks a ton!

LikeLike

Trigger warning: rape. While there a variety of responses to the trauma of sexual violence, the connections made here are highly problematic. A butch identity is an expression of femininity, not a rejection of femininity. Women who don’t conform to social expectations are not damaged; they are living out their individual preferences. Framing the options in terms of being either “modest” or “slutty” is a reflection of damaging social expectations that no woman should be referenced against. Your friend may understand her personal experience in the way you describe but there is no widespread correlation between survivors of sexual violence and butch identities. Survivors adopt various strategies for healing and making sense of their personal journeys. Survivors also have various gender and sexual identities; there is no one pathway for development. While many survivors will manage their trauma in diverse ways at different points in their lives it is not correct to presume that survivors reject femininity and sexuality. Similarly, butch identities are a gender expression and they do not signify a rejection of sexuality. Sexuality and gender are different.

LikeLiked by 1 person

gender is a concept that has continued to shape elationship between men,women,boy and girls in the society.which are the forces that have continued to shape gender relationship in the society?

LikeLike

The answer to this question is in my commenting policy above. ☺

LikeLike

Hi, I would like to reference (correctly!) some of your ideas from this piece in an essay I am writing. Did you last work on the page in 2015?

Thank you!

LikeLike

Hi Ciara,

To cite this article: Zevallos, Z. (2014) ‘Sociology of Gender,’ The Other Sociologist, 28 November.

LikeLike

Thank you for writing this. I haven’t seen such a well thought out and in-depth exploration of this topic, fully explaining how and why gender is a social construct. As a non-binary person, it’s important to see that there are professionals that think like I do. I’ve tried to explain gender to some of my straight cisgendered friends, but they really don’t get it. You make some really good points here, things I’ll have to bring up in discussions of gender in the future.

LikeLike

Hi Kaden,

Thanks for your lovely comment. I’m glad that this article has helped you think about how you might explain gender to your cisgender friends. Good luck with these discussions!

LikeLike

I am using this article for my paper in sociology! Awesome information by the way. it was very helpful to me! Do you have a date for when you polished this piece? Thank you for everything!!

LikeLike

Hi Rahime,

Thanks for your comment. I’m glad you find this useful. To cite this article: Zevallos, Z. (2014) ‘Sociology of Gender,’ The Other Sociologist, 28 November.

LikeLike

Hi Dr Zuleyza , Hope do I site this page, dates ect…

Thank you

LikeLike

Hi Jb,

To cite this article: Zevallos, Z. (2014) ‘Sociology of Gender,’ The Other Sociologist, 28 November.

Thanks for stopping by!

LikeLike

Okay, so I liked you article it was okay. That being said I feel as though you should have pulled much more from biological anthropology, and established neuroscience. While neuroscience has somewhat avoided the topic that I am going to mention right now and that is, there are way too many different labels. GLBT covers it all, it really does.

I am going to tell a really simple story. Once upon a time people lived in groups did whatever they wanted and had sex with everyone like all of the time. No one really cared about gender roles or this and that etc. they just did whatever they wanted to. Then people started practicing agriculture and property became and issue, and the amount of children within a family became an issue, and subsequently the ownership of female sexuality became an issue. From there it is all really basic history.

The moral of that story is one that is often recited. Gender is socially constructed. Its not a gradient its not a spectrum, it is completely made up entirely. Giving labels at such a high degree of specificity is simply validating the status quo and identifying an “other” for many people.

Neuroscience today suggests that there is no such thing as a “straight” woman. And that there is no such thing as an Asexual male (every male will get a boner in their sleep no matter what, every time, guarantee). Biology decides what sex is (and intersex is a real thing biologically, not a social construct) and moreover it roughly decides “gender Identity” not because gender identity is inherently a birthright or inherently biologically significant, it simply is in the fact that the brain will prefer different groups identities and actions based on the situation it is in, in such a way that makes them choose (an I am using a computational meaning of choose, not really an act of free will) to fit in as one gender or another based on the culture they are in. Instead of trying to create additional layers of specificity to try and fit all of the nuance of each individual (as this process can continue ad infinitum) the most effective approach is to realize that everybody defines themselves within gender as we know it today (meaning that they pick and choose within the modern discourse which particular label to ascribe to themselves in different situations).

This is not unique to gender identity but is a plague to the entire realm of the social sciences and psychology. More research needs to be done by neurologists before we begin classifying people as this or that, as creating a label for a person will cause them to direct their behavior within those limited constraints.

It is like this, for someone to identify as “gender queer” implies that they have to take on a completely new label for their variance on behavior rather than simply influence or challenge traditional notions of gender and gender roles. This is very destructive as it prevents people from defining for themselves what it means to be a man or be a woman, and instead tells them to “find a new label”. Human beings evolved to embrace a wide variety of sexual acts to encompass the community and build relationships. Definitions like this are very modern and creating too many labels is just unscientific nonsense. It is really much like differentiating between the Business Class Alpha Male, Working class alpha male, and the athletic/warrior alpha male. The fact of the matter is that while the grouping is useful for smaller scale analysis of particular subjects, when creating a broad conversation you have to stick with the all encompassing labels Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender covers pretty much everything (some may make a case for pansexual but that is a bit dismissive of transgender people as it implies that they are not really their identified gender or their physiological sex).

With this refinement of labels it is easy to make a constitutional case, without the need for an amendment for perfect equality for the GLBT community. All it needs is a few good court cases where Sex (a protected category) is used as a defense for protection. For example, if someone is trying to discriminate against a gay man, that would fall under the sex category because they are discriminating him because he likes to have sex with men, all else being the same if he were a woman this would not be an issue. That argument is the most solid, but it falls apart if we recognize anything beyond GLBT under the legal framework and focus on this such as gender identity and gender fluidity. Protection under the law should be priority #1 compared to nuanced identity, that kind of talk is really for college dorm rooms rather than on a broad political scale, as it focuses on intangible philosophy not particularly medically relevant. We have to remember that gender is much less biological than sexual orientation and it relies incredibly heavily on social influences. Thus trying to direct labels at people based on this, particularly children, and minimalizing the negative toll of things such as hormone therapy and sex change operations (they are quite taxing and associated with many health problems on the long term) really just creates more of a problem than anything else.

LikeLike

Hi Benjamin,

There’s a lot of word salad going on here. You have your understandings of neuroscience, biology and sociology all mixed up, as with your narrow understanding of gender and sexuality. Both gender and sexuality are social constructs – that means that categories, behaviours, identities and social expressions of both gender and sexuality have varied across time, place and culture. “Neuroscience today” does notsay that that “there is no such thing as a straight woman;” nor does neuroscience invalidate the experience and identities of asexual people. There is nothing “unscientific” (as you put it) about being genderqueer. As for your confused take on the law – Australian, American and other nation states recognise it is unlawful to discriminate on the basis of gender AND sexuality (and other protected characteristics).

Identities give meaning to individuals as they tie us to communities; they may help us express our personal values; and identities also tie us to other social experiences. Richard Jenkins shows that not all identities matter at the same time to everyone – but when social identities do matter such as during times of conflict, or when people are denied rights, or when people are excluded or victimised – then identities really matter.

Identities are not merely “labels” as you see it. As for your concern about how identities confuse children – a plethora of research, much of which I cover in this blog (for example here), show that it is not sexuality that “confuses” children, but rather the narrow-minded views of bigots who spread misinformation about sexuality and gender. If individuals were more interested in upholding the rights of sexual and gender minorities, rather than imposing their value judgements and ill-informed opinions on biology and morality, then children would not have to suffer with their gender and sexual identities.

Your transphobia is noted and you are therefore not further welcome on my blog.

LikeLike

I never said that the gender labels are confusing children. I am simply saying from a legal standpoint its easier to protect under the basis of sex than gender identity, and that is a good reason to get rid of the labels. In a sense by making labels people in the transgender community are “othering” themselves and making themselves a more easy target for descrimination.

WIth that said, I the main point of my arguement was not one about sexuality, as sexuality and gender identity are completely different. One being immutable, and the other, as fars as we are aware being highly mutable untill about halfway through puberty.

In some ways Identities can tie you to a community, but in other ways it can isolate you from other communities. The idea of someone being Genderqueer is really just a more overt aknowledgement of the fact that they do not subscribe to the traditional boundaries of gender norms. It is essentialy Agender. Much like being an atheist means not conforming to any religious norm. People in this category define themselves rahter than the gender they fit into. They simply eliminate one form of self stereotyping that everyone else does. With that said, there are a lot of scientific inconsistencies in the trangender narrative, and they only exist in an effort to fight descrimination. I am saying that beig transgender does not have to be a biological condition for it to be protected under the law. I think you are misreading my point as it really is to the support of the transgender community. The main idea being, gender is completely made up, and therfore would be as protected as other made up things such as religious identity. And that being made up does not make it any less important that things such as religious or political affiliation. And that unde the current laws as they are, discrimination against them is not allowed. You are strechting my point to something that really is not what I am saying. And I think you are being overly deffensive where you don’t need to be.

LikeLike

Sex is biological; gender is social. You don’t understand the laws protecting gender minorities and it’s clear you don’t want to. Gender is a social construction but it is still meaningful to individuals and communities, as my article explains and as I’ve already outlined. Writing a sociological post using sociology is not being “deffensive” [sic]; though you do seem to expend a lot of energy peddling your subjective ideas about gender and sexuality, which have no scientific basis. I’m only allowing your comment here to note for the last time that transphobia is not allowed on this blog. I have a clear set of guidelines about comments, which include the fact that this is a sociology blog that educates. Your opinions about how transgender people should be defined bear no weight to this discussion.

LikeLike

Hi! great article. I was just discussion with one of my colleagues a subject along these lines…he referred to gender as not social but mental. he referred to a diagnosis once given, gender dysphoria, and describes the need to fit in not because of social standards nut for mental reassurance. what is your thought on this idea? we discussed that anatomy be more for the social standings because it is a physical seen trait and gender was not.

LikeLike

Hi Clarise. Gender is a social construct, not a “mental construct” in the way you mean, for the reasons outlined in this article and in this thread. I’m afraid your colleague has an outdated view of the term gender dysphoria, which has evolved and changed in the psychological literature. Gender is not about a mental reassurance; it is about the social norms that are imposed upon people across cultures and at different points in time, as well as how individuals respond to, identify with, and challenge these norms, in ways that are meaningful to them as individuals.

Gender dysphoria as a psychological term once referred to the erroneous view that transgender identity was seen as a mental illness; this is no longer the view of mainstream psychology, which now focuses on how discrimination, social pressures, bullying and social stigma negatively impact on transgender people’s wellbeing.

As I’ve outlined above, biological aspects which are used to ascribe “sex” (including “anatomy”) do not describe gender. Gender is the social meanings assigned to various expressions of masculinity, femininity, gendernonconformity and other gender roles and identities.

LikeLike

Hi Dr Zulekya, in the society we live in, I have observed that feminist who tend to defy the traditional social functions of a woman such as cooking, cleaning, etc, and venture into leadership positions are seen as ‘wanna be men’. How can women be more involved in the construction of femininity and the change of their roles in the modern society?

LikeLike

Hi Nelson, this sounds like an assignment question, which I do not answer. What I will say is that you might need to critically reflect on your framing of gender. Women in leadership positions are not “wanna be men” and, to invert the logic of your question, women in paid work are not disengaged with the construction of femininity. Quite the opposite, women in leadership positions are punished for leading in ways that managers consider to be feminine, as I’ve shown elsewhere. Your question shows that you accept a dominant view of gender that sees “cooking, cleaning, etc” as inherently feminine and leadership as “men’s work.” Femininity is a social construction that varies across cultures, time and place. It might be good for you to read my article above and check out the sources I link to – to think sociologically you must critique taken for granted assumptions about society, starting with gender roles.

LikeLike

You are using a straw-man argument, nobody is stopping them from doing things they like as long as they are legal and aren’t hurting anyone.

LikeLike

God you’re rude, not letting your readers and yourself to see other opinions? He isn’t even transphobic. I’m sorry but you’re being close minded, he did add to the discussion but because you LABELED him as transphobic, his post doesn’t even matter. Please try to see and understand both sides as there is more than 1. Both sides have intelligent people, and both sides are right in their opinion. Please show more respect to your readers (who are respectful in their argument) you don’t agree with, it makes you look better too.

LikeLike

Hi Chester. It is not “rude” to point out transphobia, least of all not on a sociology blog dedicated to addressing the otherness of minority groups. Transphobia is not subjective; you don’t get to decide what transphobia is and what it is not. Transphobia includes attitudes, beliefs and actions that contribute to the discrimination and denigration of transgender people. Cisgender people saying that gender is determined by biology is exactly how transphobia is maintained.

Contrary to your emotional argument, there are no “both sides” to a discussion about transphobia. Transphobia is the antithesis of this blog. My commenting policy is clear: feel free to learn from the sociological research discussed, but you cannot dismiss sociology based on personal feelings. You can “debate”/ perpetuate transphobia all you like anywhere else on the internet (but please don’t – have a cup of tea instead and get better educated on social inclusion). My website is not the internet. You, a casual interloper who has parachuted here to sprout hatred, nor any of my regular readers, get to demand to use my publishing space as a means to maintain the status quo. This is research blog maintained by a professional sociologist, with commenting guidelines established to meet the aims of intersectional feminism. Giving any more air time to transphobic apologists is not part of these aims.

LikeLiked by 2 people

How do cases of intersex and transgender individuals, challenge the contemporary gender order?

LikeLike

This sounds like an assignment question. Please read my commenting policy. Good luck with your studies.

LikeLike

Can you give me some examples of you or someone you know acting gender differently in different situations? Also, I need help analyzing the components of feminity or masculinity that someone as emphasizing or downplaying in these particular cases.

Thank you so much!

LikeLike

Hi Kula. I cannot do your assignment for you but feel free to use my website’s vast resources on gender to think critically on doing and undoing gender. Best of luck in your sociological journey!

LikeLike

Why is personality equal to gender in 2016?

LikeLike

Woah, here you are again, Calvin! Here you give me your homework question; and when I don’t oblige you go and attack the social construction of gender. Read the references your sociology lecturer assigned to you; think critically about these; and then take a step back and reflect on why it makes you so upset to learn that many cultures see gender in non-binary ways.

LikeLike

Beautifully explained, thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you for reading and commenting, Before They Say!

LikeLike

Is your commenting policy nobody can disagree with you? There are 2 genders. no matter what social construct you believe in. At the end of the day there are 2 biological genders male and female, penis and vagina, women and man, he and she. If you want to get your sex change or even identify yourself as a mashed potato go right ahead but science will forever disagree.

LikeLike

Hi Calvin,

It must be very scary to live in a world where reading the science showing that the rigid laws about gender you hold dear are not, in fact, real. I make the distinction here between sex (biology) and gender (social construct). I discuss scientific research showing how gender is organised differently across time and space, including in Western nations like the one you live in, and here you are, with your personal opinions evoking the sanctity of science. Feel free to actually read the research, and take comfort: other cultures and individuals’ gender identifications are not a threat to you.

Oh, and by the way, my commenting policy clearly states that I’m happy to engage with credible sociological and other scientific evidence. You have provided neither. I am an expert in this field and you are not. You are entitled to your opinions, but not your ‘facts.’

LikeLike

I have learnt so much. Very interesting Dr. Z

LikeLike

I really found thus piece useful in ma assignment… buh who caters for the illegitimate child/children of the female- husband

LikeLike

Hi Oyindolapo. Sadly, children of female husbands are currently not entitled to inherit property and are socially stigmatised. (Important to note why I used the term “illegitimate” in quotation marks as there is no such thing as an “illegitimate” children. No human being is illegitimate.)

LikeLike

Wow so true.!

LikeLike

In school I was constantly being told by other girls to behave/be/dress more feminine, never the boys. So for me it was really more the girls who were policing gender roles. I´m wondering whether this is some form of hegemonic femininity (within the group of people perceived as women). But I see the point that hegemony would imply a position of power over people of other groups. And those women who are “successful” at being “female” don´t necessarily assume a position of power in society, maybe even less so because being feminine is also seen as incompatible with holding power? I´m curious about your thoughts and maybe some reading advice on this. Thank you!

LikeLike

Hi Passerby,

Thanks for your comment. To answer your question, is there hegemonic femininity, the answer is no. While in your subjective experience girls policed femininity, more generally, people of all genders police gender. Hegemony is the process by which the interests of elites and those in the dominant group are established through consent, often through socialisation. Hegemonic masculinity is a concept theorised by the Australian sociologist Raewyn Connell in her book, Masculinities. Hegemonic masculinity is established through various social institutions, including the media, which holds up some forms of masculinity as being the ideal (White, heterosexual, athletic, able-bodied). An example is the male protagonist of any Hollywood action film. Connell describes clearly that there is no such thing as hegemonic femininity as women do not have cultural power.

Women policing gender are actually doing the work of patriarchy (same goes for men who police gender). Cisgender men benefit most from the construction of gender as a binary, not women, because this binary positions masculinity as universal and superior.

Thanks for passing by!

LikeLike

Hey, Ms. Zevallos!

I have a question pertaining to the target audience of this article. I read, cited and I am currently doing an in depth study of “Sociology of Gender” and I am curious as to who your targeted audience was. Any information would be wonderful and graciously accepted!

Thank you!

Jaiden Raimondi

LikeLike

Hi Jaiden. This is a sociology blog for the public. See my About Me page. 🙂

LikeLike

Greetings Dr. Zevallos,

I am trying to understand the differing perspectives on gender and sex in academia. From what I have observed, being a Transwoman is not simply a case of a male feeling very feminine and then “deciding” to transition to fit society because society says only females are feminine. Transwomen state that they are women, and some are masculine, feminine, androgynous, and have various sexualities. So, I get that gender is socially constructed, but I think that there must be some sort of gender consciousness that causes a human consciousness to see itself in terms of gender, as a man, woman, or in between. And that this gender consciousness is linked to external genitals and secondary sex characteristics, because these aspects cause transgender people distress because they do not align with their gender consciousness. This consciousnesses must be rooted in neurological structures that impact human consciousness.

Consider this:

How could a person be raised in a typical female body, be raised as a girl socially, and yet always have an internal sense that they are a boy? what if this boy is also very feminine and gay, which from the outside would make him seem like a “typical” feminine girl? yet this “girl” is really a boy. Doesn’t this suggest gender consciousness that is separate from society? If gender identity can go directly against society, and be the opposite of what society dictates, it must have some function distinct and independent of society. It will be viewed through societies lens, but that doesn’t actually effect the transperson and their gender consciousness. To elaborate, a person might see transpeople as duped by patriarchy, as mentally ill, or as authentic men/women. These views do not change the transperson’s own internal gender consciousness. Someone thinking that transpeople are duped, doesn’t mean they are. I hope I’m making sense. This has been weighing heavily on me because to suggest that gender is completely socially constructed runs the risk of invalidating transgender peoples experiences because transpeople simply would not exist in a world were gender is 100% socially constructed with no neurological component that is independent of society.

LikeLike

Hi Lucas,

Gender is indeed a social construction because it varies across time, place and cultures. Neurology does not determine gender, nor does biology. Gender is the social meaning ascribed to what it means to be male and female. These ideas are shaped by society in rigid ways. Transgender people’s gender identity does not match their biological bodies. There is no such thing as gender consciousness in the way you refer to it, I’m afraid. There is no collective higher order consciousness that determines gender. The argument that you present is known as biological determinism, and it is often used to invalidate transgender experiences. Have a read of the resources I’ve cited to see varied examples of gender in different social contexts.

LikeLike

Hello Dr Z. (Sorry I like to use shorthand typing hahah) Your article has helped me out tremoundesly in my research for my class. I appreciate you going out into such an interesting field and creating a wonderful article. Again Thank you so much!

LikeLike

Thank you Collin!

LikeLike

A very nice article ..i really learn a lot of new terms there

But what can you say about gender inequality?

LikeLike

I write about gender inequality a lot on this blog. For example start with these posts and also see my publications.

LikeLike

This is not a question but rather a compliment. Thank you for this article, it has lead me in the right direction with my work on Gender and Reproductive health. I hope to continue engaging with your work further and maybe I might have some questions

LikeLike

Thanks for stopping by, Ntokozo!

LikeLike

How do cultural ideas about gender shape our understanding of the reproductive body?

LikeLike

Hi Rosalie. The answer to this question is that the joy of sociology is reading, synthesis and completing your own assignment. This is only surpassed by the sociological insights derived from reading my commenting policy. Good luck with your assignment!

LikeLike

I’m sure you’ve read the John/Joan case. If not you should.

LikeLike

TW: suicide and depression.

Hi Juan. Thanks very much for your comment. I have indeed – David Reimer’s case shows the tragic circumstances of medically-driven gender interventions that ignore the wellbeing of individuals. His case is also important for medical ethics, due to the doctors and psychologist who obscured facts about his medical history and profited from his experience.

For others reading along, if you read further into his case, Reimer died by suicide after a long battle with depression.

For a succinct overview of his case, see the Intersex Society of North America, who write: “We like to point out that what the story of David Reimer teaches us most clearly is how much people are harmed by being lied to and treated in inhumane ways.” http://www.isna.org/faq/reimer

LikeLike

I noticed that in an image explaining sex, gender, and sexuality, that intersex was listed as an example for gender. I believe that that is inaccurate, at least to some extent. Being intersex is a chromosomal variation other than XX or XY (XXY, XYY, XXX, etc). I acknowledge that some intersex people may identify their gender as corresponding with being intersex, but I still believe that intersex should be used as an example of sex rather than gender. Can I know your opinions on this?

LikeLike

Hi Aeyrn, thanks for your question. Intersexuality is a gender identity. While “sex” refers to biological descriptions, people who identify as intersex are describing their unique gender identification and experiences. That is, the social aspects of their masculinity/femininity/genderqueer or other gender identifications. Their biological status (having a unique chromosomal “variation” from XX or XY for example) does not define their gender identity. In fact, intersex people show that gender is a fluid social construction. For example: who decides that XX = certain body parts = woman? This scientific definition emerges from a Western definition of sex. There are so many biological combinations that are found amongst humanity that a binary sex/gender do not adequately capture. Sex = defined by convention. Gender = defined by social meaning, including individual expression and experiences. Hope that helps!

LikeLike

Hi I’m currently doing an assignment on sociological perspectives on gender – mainly how biological determinism and socially constructed notions of gender are used to explain gender differences…

I was hoping to use functionalist and marxist-feminist theories to compare, could you recommend any good names to read up on for any theories that will help me with this assignment?

LikeLike

Hi Becky. My commenting policy has all the answers you seek.

LikeLike

Truly intriguing to read as I apply a lot of what you write here to how i view myself.

LikeLike

Hi Tarnished Soul,

Glad that this resource has resonated with you! Best wishes, Zuleyka.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your article does a great job showing that gender norms vary across cultures and are therefore socially constructed. Do you think biology influences the construction of such roles? For instance the fact that women give birth and produce milk may have made them more likely to take on a more active role in raising children, whereas the advantage in a fight that men have from being stronger on average than women may have made them more likely to take on a more active role in (pre-gun, melee) warfare.

LikeLike

Hi Inertia. Biology has no influence on the social construction of gender. When we talk about this concept in sociology, we are showing how social meaning is ascribed to certain biological characteristics. You’ve given the example of “producing milk.” Well, not all mothers are able to lactate, for starters, and not all women are mothers. Also in many cultures, including in Western European cultures until the advent of the industrial revolution, women either did not lactate if they were rich, or they would swaddle their babies to keep them restrained while they worked long hours of demanding physical labour. See The Making of the Modern Family by Edward Shorter. Similarly, there is wide variation in how societies organise combat, with women often taking on such “warrior” roles, from military leaders such as Ahhotep I and Hatshepsut in the 17th and 15th Centuries, to The Lady of Yue and Huang Guigu in the 5th and 3rd Centuries, to the Tausug women in the Southern Philippines when their communities were being invaded, to women who work in wrestling and combat sports in the present day, and many groups in between. The fact that there is variation in women’s physical abilities shows that there is no biological restriction to how gender is organised. The differences emerge due to cultural, historical and social context.

LikeLike

This was such thorough and helpful information. Thank you so much for your dedication and expertise when gathering all this information! When people come to me with arguments about sex vs gender, I always have to search through all these not-so-quite-what-I-need articles on google, and then I found this! Absolutely great, thanks again!

LikeLike

Thank you Paulina. I’m pleased this my work has been helpful! Appreciate the feedback.

LikeLike

Hie How and why does gender affect health

LikeLike

Hi Pamela. All my health posts from this blog are here: https://othersociologist.com/tag/health/

Please be sure to check my commenting policy before posting: https://othersociologist.com/about/commenting-policy/

LikeLike

Hi there,

Thanks for the article.

One thing I’ve been struggling to understand is how gender can be both a social construct and a personal identity. I haven’t quite been able to wrap my head around this.

As I’m sure you know, gender as a social construct has been used as an argument by some transexclusionary feminists against the existence of the concept of gender identity (and, therefore, transpeople). They say gender is not something you feel, but something imposed on you by society.

I reject their conclusion, but I also haven’t been able to form a satisfactory rebuttal to this line of thinking. Am I missing a key detail? Is it a strawman argument? Is there actually no conflict between gender as identity and gender as social construct? What am I missing here?

I’m going to keep reading and thinking about this and trying to muddle through it on my own, but I’d appreciate any thoughts you have on this subject.

Cheers,

Sarah

LikeLike

Hi Sarah. I’ve answered versions of this question many times on this page as you see in other comments. Gender, as I describe in this article, is the social meanings attached to notions of masculinity, femininity and other expressions that draw on, or reject, these ideas in various ways, such as agender people who don’t ascribe to a gender binary. Gender is a personal identity because it cannot be dictated to you. It is about your understanding of your social experiences, including socialisation, cultural norms, behaviours, embodied preferences, and other ideas. Gender as a social system tries to control these identities and expressions; in Western cultures, by setting up “man” and “woman” as two opposites, but as I’ve shown, cultural variability across time and place shows that many other gender categories and understandings exist.

“Feminists” who are exclusionary of transgender women are not feminists at all, because feminism seeks the gender liberation for all people, with a specific focus on the inequality faced by all women. Transgender women, are women. Anyone who disagrees is contributing to gender inequality.

LikeLike

“Entrenched gender inequality is a product of modernity”. Despite gender inequality being present, I do believe that certain characteristics are biologically/genetically inherited. if you look at the caveman era, the mother would care and feed her infant whilst the father would hunt for food. Certain things can not be argued against, such as the fact that only the woman is able to breastfeed. Yes inequality does exist, but sometimes people seem to exaggerate this inequality by trying to defy nature.

LikeLike

Hi Luca. You are entitled to your beliefs, but unfortunately not to your facts. And the fact is that there is no “caveman era” as you describe it, as anthropological evidence shows pre-modern societies had far more varied social systems than previously thought. Another fact is that not all women breastfeed. Some women cannot breastfeed for a variety of reasons, whether it be their child’s suckling technique, or complications with their bodies. Other women may not breastfeed because they are transgender, while others simply choose not to breastfeed. In fact, across time and in many cultures, entire groups of women would not breastfeed, such as aristocracy in England or slaveowners in Australia and the USA who used nursemaids. These are complex examples of how nature does not dictate gender inequality; instead, social organisation of gender reproduces class, racial and other gender inequalities.

LikeLike

I totally get your point and agree, but there are facts which we can’t deny, such as the fact that males are physically more dominant, due to the biological structures such as hip structures and natural muscle mass, these things can not be argued against as they are facts, take sports for example…get the fastest male time in any olympic sport and compare it to that of the fastest female, statistics do not lie

LikeLike

Hi again Luca. No men are not physically more dominant. You’ll have to work out why you are so heavily invested in your false notion that women are inferior to men elsewhere, although science already has an answer for why people refuse to believe science. Good luck with your journey out of patriarchy!

LikeLike

Your argument regarding breastfeeding is ridiculous, he was stating the FACT that only women and NOT men are capable of breastfeeding, not that some can’t or choose not to, but PHYSICALLY CAPABLE! You are very argumentative when someone doesn’t agree with your “empirical” data and completely delusional if you refuse to acknowledge the physical differences in men and women, they exist, that’s empirical data

LikeLike

So I found this article while looking for resources about gender being a social construct. My friend did a version of the I identify as an attack helicopter meme and I’m trying to explain to then why that is upsetting and wrong.

I’m cis gendered and having trouble finding the words to say that yes gender is a social construct and how people identify themselves is still valid and should be respected. If you have any reading suggestions or good arguments I would love to hear them because I’m having trouble.

LikeLike

Hi Emily. You can use the examples on this page to explain how gender varies across cultures and how it’s changed over time, including in Western societies. You might try having a conversation about why your friend feels so upset over the fluidity of gender and ask them to reflect on the gaps in their knowledge about how gender is organised in different societies.

LikeLike

The social construct theory of gender is one of the best examples of circular reasoning I’ve ever encountered:

Premise 1: Some obscure societies practice non-binary gender

Premise 2: Western and industrialized societies practice binary gender

Consequent: Western and industrialized societies are wrong.

You asked a commenter to reflect on why the idea of other cultures practicing different beliefs causes them so much discomfort, have you asked yourself the same? I mean here you are, ragging on western culture, because it doesn’t agree with you.

You should also ask yourself why the majority of advanced nations practice binary gender while some obscure societies that either no longer exist or currently exist in turmoil don’t. You use countries in your argument that are overrun by rape, murder, and a callous disregard for human life. You know what they do to homosexuals in Nigeria, don’t you? Here’s a quote from a recent article “Nigerian prosecutors have charged 53 people for allegedly witnessing a same-sex marriage, which is punishable by 10 years in prison in the socially conservative West African country”. http://www.newsweek.com/nigeria-same-sex-marriage-586746

Another article relating to their issues:

https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/10/20/tell-me-where-i-can-be-safe/impact-nigerias-same-sex-marriage-prohibition-act

So Nigeria is really a country we should model ourselves after, right?

And before you jump to your classic “biggot” “transphobic” “homophobic” etc. garbage, understand that I have an assault charge for breaking the nose of someone who was harassing my transgendered co-worker. I am for absolute freedom, and I will call someone whatever they prefer if it means that much to them. However, gender is not socially constructed. Sorry.

LikeLike

Hi Turnur. You seem upset that other people have different gender experiences. Becoming better educated about your prejudices and unfounded fears is the first step to letting go of this angst. To answer your muddled statements, there is no such thing as “obscure societies.” All societies are equally valid. Your narrow worldview leads you to think that your personal experience of a tiny corner of the world must be the ideal, when it clearly isn’t, as evidenced in the empirical documentation I’ve provided in this article. The majority of nations don’t practice a binary in a vacuum; first, as I’ve already chronicled, all societies have changed in how gender norms have worked over time. Second, the nations that impose a binary do so due to centuries of colonialism, where narrow gender categories and other social hierarchies were introduced to enslave minorities, strip them of their existing social structures, and to justify and maintain inequality.

Nigeria is a beautiful nation; like many countries it has problems with same-sex acceptance. No better than say, the USA, where violence is an everyday occurance for LGBTQIA people, and where a mass-murderer specifically targeted and killed 50 people and injured a further 58 people, for nothing other than masculine violence fuelled by homophobic rage.

I’m sad to confirm for you that you are indeed a bigot and a transphobic person, or you would not have been so incensed as to leave such a verbose comment putting your homophobia on show. Anonymous men often make up valiant scenarios that are meant to shield them from critique. Anyone who has genuine respect for, and personally supports, transgender people would not stoop to the points you make here, and they also know not to use the term “transgendered.” Nice try. 😉 I wish you all the best as you find your way out of this place. Things will improve when you better understand and work to overcome your prejudices of gender minorities.

LikeLike

Hi there! Im writing an original oratory about the difference between sex and gender. I was wondering as a professional what you think the problems of people thinking that sex and gender are the same thing and what that is causing in society? Also, what we at home can do to stop this from happening? Love the article! Thanks.

LikeLike

Hi Payton. Check out my commenting policy for your answer.

LikeLike

Hello my question is how is gender inequality analyzed in various social institutions?

LikeLike

I’ve read through your research but you haven’t made mention to Gender and health. do you not think gender has also affected how we view health and the transmission of sexual disease. for example in the past being a “homosexual” was considered you were considered to be a carrier of the HIV/ AIDS virus.

LikeLike

Hi Dezion,

Homosexuality is not gender. It is sexuality.

LikeLike

As usual. If you don’t agree with a liberal they become as nasty as a fascist. People are allowed to disagree with your hypothesis that gender is not merely a social construct!

LikeLike

Hi William,

Fascism is a political system that uses autocratic rule, violence and censorship of public dialogue to restrict individual freedom. This is a sociology blog. That gender is a social construct is not my “thesis” – it is documented in scientific articles, which I’ve cited.

LikeLiked by 1 person

William: You have the right to disagree, but that doesn’t make you correct.

LikeLike

Now days we should give opportunity the women because they are important in our society by teach youth on how to live in their society (something called self determination) which is important to all human being in specific society.

LikeLike

hello,,,i wanna ask about the function gender so how to see the function gender of female masculinity,

LikeLike

Hi Zuleyka. Can you write a conclusion of this essay please.