This page is a resource explaining the sociological concept of sexuality. I provide an overview of sexual practices in Australia and cross-cultural examples where “institutionalised” or socially sanctioned homosexuality have been endorsed. The examples I cover are focused on experiences of otherness.

On my Sociology of Gender page, I’ve noted that sociology differentiates between sex, gender and sexuality.

- Sex is the biological traits that society associates with being male or female

- Gender is the cultural meanings attached to being masculine and feminine; these influence personal identities across a wide spectrum.

- Cis-gender describes people whose biological body they were born into matches their personal gender identity. This gender experience is distinct from being transgender, which is where one’s biological sex does not align with their gender identity. Intersex people are born with “ambiguous” sex, which might include their genitalia, reproductive organs and chromosomes.

- Sexuality describes sexual identity, attraction, and experiences which may or may not align with sex and gender. This includes but is not limited to heterosexuality, homosexuality (gay or lesbian), bisexuality, queer and so on. Sex and gender do not always align.

Just as gender is a social construction, so too is sexuality. This is another way of saying sexuality is socially determined and it varies in its expression across culture, time, and place.

Sexuality

Western society constructs heterosexuality as the norm, but this wasn’t always explicit. As sociologist Michael Foucault has shown, the invention of the word ‘homosexual‘ only emerged during the Victorian era in the late 1800s. Queen Victoria wanted to stop male aristocrats from having sex with other men, something that was not openly talked about, but still practised. There was no word for men having sex with other men, and Queen Victoria charged her physicians with studying this phenomenon. Having established a word for this, homosexual, these medical doctors invented a counter-position, that of the heterosexual. Thus it was the will of one woman who established the latter as the “natural” and normative position from which human sexuality was henceforth categorised. This history shows that by its very invention of the word, homosexuality was set up as the Other of heterosexuality.

Homosexuality became medicalised, and doctors were charged with “curing” it, and it was soon outlawed. This history stays with our laws in the present day, and it explains why homosexuality is largely outlawed in British colonial states (it is illegal in 41 of 53 Commonwealth nations). This history also puts into context why most former European colonies have a higher age of consent for male-to-male sex than for male-to-female, or even female-to-female sex. Queen Victoria refused to believe that women would have sex with other women, which is why the laws today reflect more leniency (though not necessarily social acceptance).

Heterosexuality quickly became welded to ideas of sex categories – to be a man was to be a heterosexual man; to be a woman was to be a heterosexual woman. Heterosexuality – an idea that has only existed since the late 1800s – became normalised in the early 1900s. The alternative was to be legally punished. Judging gender and sexuality according to heterosexual norms is known as heteronormativity – the expectation that heterosexuality is “natural” and therefore needs no explanation. Homosexual people are expected to “come out” and identify themselves only because they are different to heterosexuals, and yet heterosexual people are not expected to publicly announce their heterosexuality.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and Asexual (LGBTQIA) people are excluded because of how heteronormativity functions: it makes non-heterosexual people as Other, even though homosexuality has existed throughout human history. In many cases as I show below, homosexuality was permissible only for elite groups, or controlled for certain periods of time. In one way or another, all societies restrict the expression of sexuality, but the idea that heterosexuality is the mechanism by which this happens is false. Sexuality is historically and culturally variable.

Sexuality in Australia

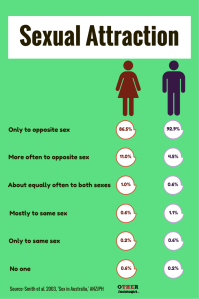

Nationally representative surveys in Australia, the USA, and other nations show that human sexuality is diverse in its expression. In Western nations, the general figure often quoted is that 10% of people are homosexual. This is not right; the statistic comes from the pioneer Kinsey Study, who drew on a large, but skewed sample of volunteers who were highly sexual. Thus the sample over-inflated certain figures. Nowadays, we rely on randomised surveys to get a more detailed population overview of sexuality. The results may still be surprising, demonstrating that most people do not adhere to society’s definitions of what it means to be heterosexual or LGBTQIA.

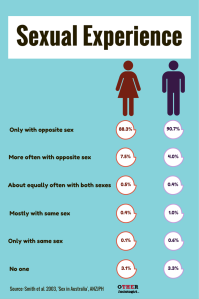

In Australia, the Sex in Australia study by Professor Anthony Smith and colleagues drew on a nationally representative survey of over 19,300 Australians. The results show that around 97% men and women identify as heterosexual, with slightly more women doing so. Less than 2% of men identify as homosexual, and less than 1% of women do the same. Similar rates of people identify as bisexual, though slightly more women do so (1.4%) in comparison to men (0.9%).

Then again, around 7% of men and 13% of women have been attracted to the same sex at least once in their lives, while 6% of men and 9% of women have had a sexual experience with someone of the same sex.

More women overall report same sex attraction that they have acted upon. Most heterosexual-identified people have only had one same-sex experience in their lives, with women doing so much later than men, usually after the age of 21 years. Men have slightly lower same-sex attraction in comparison to women. Men are also less likely than women to act on this attraction. This is likely due to the additional stigma placed on gay men, which stems from the historical policing of male homosexuality. More men report psychosexual disturbance – a sense of confusion about their same sex attraction. Again this may be possibly due to the cultural stigma about gay men which either causes heterosexual-identified men to experience anxiety about same-sex attraction, or perhaps they are reticent to act out on their same-sex desire. The researchers also argue that not acting on same-sex desire may lead to psychosexual anxiety for men. Conversely women may report psychosexual disturbance less because they are more likely to act on these attractions.

The researchers also note that same-sex desire for women has a slightly more visible “sex script” in popular culture. For example, a flirtatious version of lesbian sex is written into mainstream music and movies as well as pornography – albeit all aimed at heterosexual men. Women may therefore be more open to same-sex desire because it is (relatively) more familiar and somewhat less repressed. Male-to-male sex is less visible; it occupies a separate space in the sex industry, and gay relationships are largely de-sexualised in popular culture. This is not to say that lesbian and bisexual women do not experience harassment and discrimination, it’s just that men who currently identify as heterosexual are less comfortable with same sex desire than heterosexual women.

If we take sexuality to be either sexual attraction or experience, then 9% of men and 15% of women report experiencing same-sex desire. Around 60% of gay men have had sex with a woman and 82% of lesbians have had sex with a man. Amongst men who identify as heterosexual, 91.4% have only had exclusive attraction and sexual experiences with women, while only 84.8% of heterosexual women report this exclusive experience and attraction to men. Almost three times as many heterosexual women have experienced attraction towards women that they had not acted upon (6.2%) relative to heterosexual men with desire for other men (2.5%). In a follow up book, Doing it Down Under, two of the researchers, Professor Juliet Richters and Professor Chris Rissel write:

It seems that in Australian society it is easier for women than for men to acknowledge and act on same-sex desires, while retaining a primarily straight identity.

Heterosexual people who are tertiary educated and working in white collar or professional jobs are most likely to have had a same-sex experience. Higher education lends itself to greater tolerance for experimentation and access to diverse experiences (not withstanding prevailing prejudice and homophobia).

LGBTQIA people are as diverse as the communitites in which they live. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, this means dealing with exclusion and racism as well as homophobia. Watch poet/ actor/ comedian Steven Oliver who claims his identity as a gay Aboriginal man in the face of interconnected forms of inequality (a phenomenon known as intersectionality).

As I’ve discussed elsewhere, the Sex in Australia study was unable to identify the specific patterns of sexuality of transgender and intersex Australians. Other research shows that sexuality amongst transgender and intersexual people is not determined by biological sex or medical intervention. This means that gender transition or surgical procedures do not lead to one set of sexual practices over another. Transgender and intersex people may identify across a broad spectrum of sexualities from heterosexual to queer and beyond, and this may or may not shift over one’s lifetime.

As you can see, the sexual continuum is far more complex than the old myth of 10%.

Asexuality describes a spectrum of people who generally don’t experience sexual attraction. They have had sex before, but perhaps never; they may be in romantic relationships or in aromantic relationships with people of various genders, but not have sex. One commonality is that asexual people are often met with confusion or rejection when they come out to their families and friends. Asexual people have even met stigma when marching at the Mardi Gras (Australian’s national pride march for LGBTQIA people). People misunderstand how people could reject sex altogether.

Cross-Cultural Perspectives

There are various cultures that recognise non-binary sexualities, with many examples found amongst so-called “warrior” cultures. Below are just a few examples. It is tempting to describe these as examples of either homosexuality or transgenderism, but I note that cultural and historical context matters. For example, in my analysis of Two Spirit practices amongst Navajo groups, I noted that social scientists have used this tradition as an example of transgender experience, but some Native American scholars dispute this position. While some Native American activist groups are embracing the Two Spirit label, they do so with stronger respect for this as a spiritual position, rather than simply as a sexual identity. Other non-Indigenous activists have been co-opting the Two Spirit experience to advance Western ideas about LGBTQIA politics which may not resonate with Native Americans, or which ignore issues of racism within LGBTQIA communities. It is important to be careful when discussing the sexual and cultural practices of Others given the history of violence amongst colonised and minority groups.

In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who are transgender women are called sistergirls (see the Tiwi Sistagirls below) and transgender men are brotherboys. They navigate racism and transphobia in broader society, racism within LGBTQIA groups and possible alienation from their communities. For these groups, gender identity is also about spirituality and connection to culture and Country.

With this in mind, let’s delve into the past to examine sexual diversity, reflecting on issues of intersectionality along the way. Most of the documented examples of non-binary practices of sexuality involve high-status men. Undocumented examples may reveal other patterns, as I briefly show. Still, note that power, gender and class underscore these historical examples.

Pederasty

The practice of pederasty has been found in every major continent at different points in history. It involves an adult male initiating a sexual relationship with an adolescent boy, but these relationships were not always constructed as romantic in the sense that Western cultures see this word today. Many people know these relationships were found amongst the upper classes of Ancient Greeks and Romans; perhaps most famously are the Spartans. In some contexts, the relationships were about cementing a profound friendship; in other cases, they were mostly platonic; and in other cases again, the relationships were more exclusively sexual, although adult males might still have sex with women.

Some Ancient Celtic groups also engaged in this practice, as did Ancient Persians, and in some cases this might involve castrating young boys. Other examples are found amongst the warrior class in feudal Japan; in Italy during the Renaissance; in Russia during the medieval period; in Spain during the Moor rule; in China from the 10th Century up to the early 20th Century; various islands in North America prior to colonisation; among the Yucatecan, in Mayan culture in Mexico, which persisted until the late colonial rule of Spain; and in 19th Century England amongst elite aristocracy, artists and poets. There are many more examples, but let’s delve into some case studies.

The Nanshoku (Japan)

The Nanshoku were a class of Buddhist monks who were allowed to take young monks-in-training as lovers in a relationship that was considered serious and binding until the young boy grew up or left their training at the monastery. The practice began around early 800 BCE, and like most of the examples below, are only permissible to men of a high status. The samuarai bourgeoisie (elite class) also engaged in this practice during the early urbanisation of Japan, when men greatly outnumbered women as cities were still being built. During the 17th and 18th centuries, high class tea houses and to a lesser extent, kabuki playhouses, provided male sex workers to fulfil the samurai’s sexual desire for “beautiful” men. These practices were eventually eradicated as more women emigrated into the cities and because the government clamped down on male sex workers.

The shudō warrior (Japan)

The shudō warrior practice bound an older warrior who would train and protect a younger warrior. They entered into a monogamous male relationship, though they were both free to continue having sex with women. Their sexual relationship would end once the boy became older but their friendship and mentorship was ideally maintained for life. Love, trust, mutual appreciation and sacrifice underscored these bonds. This practice is meant to cement loyalty between men who fought alongside one another. These relationships arose because women were largely prohibited from entering “this masculine world of honour and violence.”

The Sambia (Papua New Guinea)

The Sambia are a tribe in Papua New Guinea who, up to the 1970s, practised a form of institutionalised homosexuality. Young boys and girls live with their mothers separated from the men. At around age six to ten, boys are taken to live with the men. Ingesting semen is seen as a way to strengthen their masculinity and purify them from their feminine influences. During this time the boys undergo various rituals, including body piercing (of the nasal septum) and set nose bleedings, and they are also taught to hunt and fight. Younger boys fellate older boys who are in their mid-to-late teens, and as they grow up, they become the fellated. Once they reach marriage age and have children, sexual contact between men and boys is prohibited.

Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Women

Other than the Two Spirit tradition amongst some Native American cultures, there are few well-documented examples of societies allowing classes of women to engage in same-sex or bisexual behaviours. There are more records of societies allowing male-to-female gender change than the reverse (also known as “the third gender”). The Tupinamba tribe of Northeast Brazil is often cited as an example of accepted lesbianism and an alternative gender but records are sketchy. References by colonial Portuguese say some Tupinamba women “lived as men and were accepted by other men, and… hunted and went to war.”

It’s not that women didn’t have lesbian and bisexual relationships – there are literary, artistic and historical examples, most famously the Ancient Greek poet Sappho. Yet these cases are generally not socially sanctioned, ritualised or institutionalised to the same extent as same-sex relationships that have been allowed for (elite) men. This is an outcome of most societies being patriarchal, and conferring special rights and privileges to men over women. Adrienne Rich documented this historical pattern using the idea of compulsory heterosexuality, which has been forced upon women for much of history, in many (though certainly not all) cultures.

Historical records have largely been written by men about men, so again, women’s same-sex practices have been lost. It is sadly unsurprising that records of women’s sexuality have not survived colonial genocide and violence, that specifically targeted women through rape and forced intermarriage.

Elsewhere, I’ve discussed some interesting examples of cultures allowing women living their lives in non-binary genders (as “female husbands” for example), but this does not always permit them to have socially sanctioned sex with other women. As cultural anthropologist Professor Ted Fischer explains in the video below, cultures that allow homosexuality between men but not women have “a very deep suspicion of women”:

Woman is seen polluting, as dangerous, as someone who would suck a man’s life blood out of them, and so in these cultures there’s still heterosexual bonds, and heterosexual relationships and that’s the norm.

As I noted above, in Australia today, where heterosexuality is the norm, more heterosexual women report acting on same-sex desire relative to men, whereas global records of women’s same-sex practices are largely missing. Perhaps it is only at this period of time, following sex-wave feminism, that social scientists are able to capture these patterns. Yet historically and cross-culturally, it has been men who have enjoyed more latitude to engage in same-sex practices, up until recent centuries. This shows how much culture shapes sexuality. These patterns go against conventions of sex and biology that many people in Western cultures draw on when thinking about sexuality.

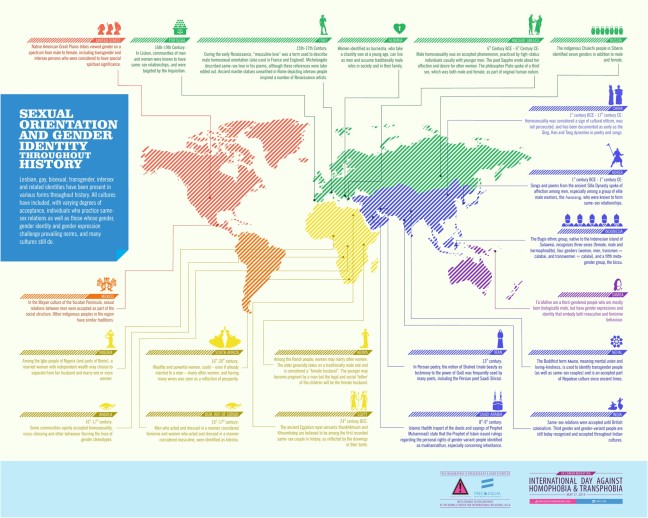

The map below illustrates more cultures that similarly recognise gender roles beyond male-female and sexual orientations beyond heterosexuality (click to enlarge).

Notes

‘Me I am,’ by Steven Oliver – proud descendent of the Kuku-Yalanji, Waanyi, Gangalidda, Woppaburra, Bundjalung and Biripi peoples.:

“I am me. Me I am, understand?

Probably not! Probably got, confused along the way.

All of this Straight, Bi, Gay. Black, Yellow, White! Confusing right? I mean, how do I dignify how I identify? How is it I find my place in a race that graces the face of this Earth. And what is my individuality worth?

My head gives birth and hurts with all the thoughts of what I’ve been taught yet,

I know nothing! I think?

You are you! True? I am me yet bound by commonality are we!

Australian, Aboriginal, Man, Human, Gay!

Identity! It is not labels. Names do not make me who I am.

Who I am is someone so profound that words can never define.”

Learn More

Read my related posts on sexuality & LGBTQI issues

- Sociology of Gender for more cross-cultural comparisons

- Rethinking Gender and Sexuality: Case Study of the Native American “Two Spirit” People

- Cyclical Moral Panic Time: Attacks on Same-Sex Families Defy Science

- In-Between Change and Antiquity: Australian Politics and ‘Gay Marriage’

- Megan Smith: STEM Woman in the White House

- The “Cult of the Clitoris”: Policing Women’s Sexuality in England During WWI

- Noble Savages and Magical Pixie Conquests: Colonial Fantasies in Film

- Erotic Capital & Beauty: How Sociology Can Help Explain Desire & Sex Appeal

Note: This page is a living document, meaning that I will add to it over time.

Citation

To cite this article:

Zevallos, Z. (2014) ‘Sociology of Sexuality,’ The Other Sociologist, 28 November. Online resource: https://othersociologist.com/sociology-of-sexuality/

Hi! I’m enjoying your blog. I’m a master’s student with a strong interest in sexuality and I’d like to read some classic theoretical works over the summer – other than Foucault and Butler, do you have any suggestions on where to start?

Thanks!

LikeLike

Hi Claire. There’s a list of suggested references above and you can also check out my Sociology of Gender page for other resources: https://othersociologist.com/sociology-of-gender/

LikeLike

Hi i think your blog is interesting and it helped in so many ways and im very grateful for that. C:

LikeLike

Hi Bryan. Thanks very much! I’m glad my blog has been useful to you. Appreciate you stopping by to let me know. 🙂

LikeLike

Yes, I enjoyed your descriptive article on sexuality, etc. I hold a M.A., in sociology, from Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA. It’s my desire, to teach a course on the sociological ramifications of sexuality.

LikeLike

Hi Patrick. Thanks very much for your comment. Great to know my article has resonated with you. Good luck in your journey towards teaching the sociology of sexuality!

LikeLike

Discovered your site just in time for my summer sociology class on sexualities. I just finished teaching a course on global sexualities. Wish I had discovered your work before that, as I would have included links to your work. Thanks!

LikeLike

Hi Sineanahita. Thank you very much for your kind words. I’m glad that my site has useful materials for your sociology courses. Lovely feedback, thank you!

LikeLike

Hi Zuleyka!

I loved reading this and found it really helpful with my assignment on LGBT community and social construct of sexuality. I would like to reference parts of it in my work and wondered when this was written so I can add a date to my reference?

Thank you!

LikeLike

Hi Liv. Thanks for stopping by! The reference to this article is at the bottom of the page, under Citation.

LikeLike

Hiya! I would also love the reference this piece but I can’t find the ‘citation’ anywhere at the bottom of the page it’s just social media links, I was just wondering when this was posted? Many thanks!

LikeLike

When was this published?

LikeLike

I’m doing some research on how sexuality contributes to social identity , any reading recommendations ?

LikeLike

this is trash, you might as well just tell people that red is blue cause that has more truth in it then this stinky pile of garbage.

LikeLike

Hi Jason,

Sociology of sexuality has clearly upset you. That’s a shame, though you don’t provide any specific scholarly evidence for what points you object to. That sexuality varies across cultures and within societies is not such a scary thing, when you can accept that people being different to you does not actually hurt you.

LikeLike

Hi, I really appreciate your intellectual conversation.

I am a master student working on religion and sexuality in sociology.

Please, I need more guide and references.

LikeLike

This is fantastic, please keep up to good work

LikeLike