In this second post in my Sociology of AI series, I show that AI companies position automation as being superior to human labour. I review the Australian Government’s recent announcement that is considering changing the law to allow AI to mine copyrighted works. I will show that the economic model used to justify this decision lacks robust testing. I analyse the ways in which AI discourse is ‘manufacturing consent’ to control the labour market. I argue that AI discourse establishes economic power by marketing technological supremacy, using science selectively, eliminating competition, and suppressing issues that undermine AI domination.

Summary

- Technology companies talk about AI in the same way. This is known as a discourse. Companies say that AI works better and faster than people. This idea helps companies grow more powerful

- The Australian Government has published a report. It says that AI will greatly improve our economy. This idea comes from an academic theory. It has not been tested in the real world. It has not been properly adjusted to our population. It does not tell us what might go wrong for workers

- The report looks at what AI could give us in the future. It does not consider negative issues

- AI companies are using the same tactics as big media corporations. They trick society into letting them take over their competition. This means they get more influence in government and other institutions. This is known as ‘manufacturing consent.’ To do this, AI companies use four tactics

- The first tactic is letting a few corporations buy lots of different AI companies

- The second tactic is changing the laws, so AI companies get what they want. Australia might change our copyright law. This would allow books and art to be used to train AI. This will have a negative impact on the creative arts industry

- Privacy laws might also change to let AI companies get people’s private information

- The third tactic is letting rich owners of AI companies sit on important government committees. This gives them influence over our laws

- The final tactic is putting AI into many existing products. This is known as ‘market cannibalisation’

- AI discourse helps technology leaders get more control. It uses some ideas from science. This gives it more authority. AI discourse is used to get rid of competition, especially artists

- AI companies hide the real cost of using AI. This includes damage to the environment and First Peoples

- We need to think more critically about the way AI is marketed

1. AI discourse is used to gain power

Drawing on the work of Michel Foucault (1963) and (1969), as well as discourse analysis, I will demonstrate how AI discourse is manufactured and maintained. Discourse is an established way in which language is structured and used to exercise power.

My analysis explores how AI companies establish a discourse of technological supremacy over human labour. I begin by showing how social policy is being shaped by AI discourse and its impact on the labour force.

2. AI discourse is shaping social policy

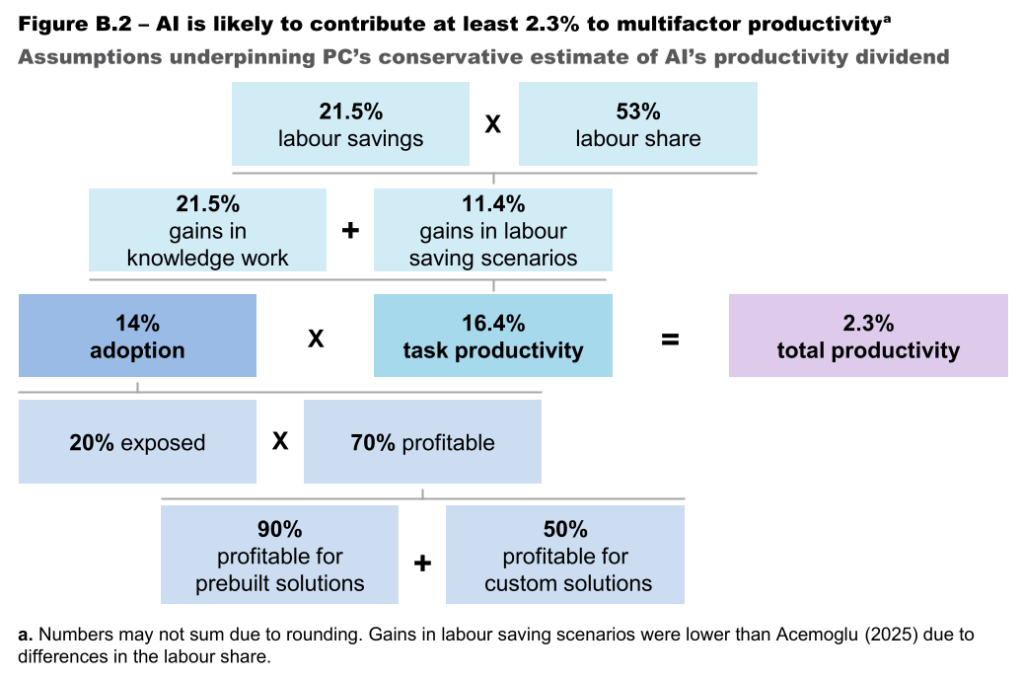

On 5 August 2025, the Productivity Commission (henceforth The Commission) released its Interim Report, ‘Harnessing Data and Digital Technology.’ The report states the Commission has made a ‘back of the envelope’ calculation that, ‘AI is likely to contribute at least 2.3% to multifactor productivity.’ This is measured by estimates of labour savings (e.g. factory automation), ‘gains in knowledge work’ (e.g. programming), and other assumptions (see Figure 1 below). The Commission says this translates to an additional $116 billion to Australia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over the next decade. The report states: ‘In the long term, AI has more potential to transform the economy’ (my emphasis).

This is the key way in which AI discourse is established, by talking about AI supremacy and its hypothetical economic potential.

The Commission generates its productivity estimate by modifying the conceptual framework and calculations of Turkish-American economist, Professor Daron Acemoglu. Acemoglu’s model extrapolates on the economic activities that AI may be able to undertake (‘task-based estimates’), by multiplying the average productivity improvement per task. As I discuss in the next post in the Sociology of AI series, task-based analyses are an imperfect measure of AI value. AI may be able to complete tasks, but there is a high error rate, of 60%. Additionally, task completion does not mean that a task outcome is better quality than a human worker.

Acemoglu’s paper presents a theoretical model, drawing primarily on two studies to generate ‘back-of-the-envelope numbers.’ This is a legitimate scholarly approach. Theoretical models are designed to be subsequently empirically tested in lab experiments, fieldwork, and randomised control trials, however, calculations must be adjusted to the local context. For example, the USA has a population of over 340 million people. Australia has 27 million people. Their GDP is over $29 trillion. Our GDP is $1.7 trillion. The USA’s manufacturing and technology sectors are larger. Such socioeconomic differences do not seem to have been adequately adapted in the Commission’s estimate.

Additionally, Australia has unique environmental challenges, including water shortages, energy issues, droughts, and other ravages of climate change. AI requires heavy water and power (more in a future post in the Sociology AI series).

Environmental costs are not adequately factored into the Commission’s calculations.

2.1. AI policy has not measured negative impact

Acemoglu’s paper notes that increased productivity of ‘low skilled labour’ will not reduce inequality. Instead, Acemoglu argues that:

‘AI is predicted to widen the gap between capital and labour income’ [my emphasis].

Professor Daron Acemoglu, economist (2025)

The Commission makes a cursory mention of inequality, only once (p.14), but this is not factored into its estimates.

On 5 August, Professor Stephen King, Commissioner at the Productivity Commission (previously Professor of Economics at Monash University), told ABC Radio National that the Commission has not analysed potential job losses.

‘We haven’t looked explicitly at the changes in the labour force… Not everyone will be a winner. There will be people who lose their jobs because of this technology. Those people have to be looked after.’

– Professor Stephen King, Commissioner, Productivity Commission (2025)

Why is AI discourse having such rapid impact on social policy? Part of the answer lies in the behavioural biases of policymakers, which are being exploited by AI discourse.

2.2. AI discourse exploits policy bias

A World Bank study by behavioural economists, Dr Sheheryar Banuri, Professor Stefan Dercon, and Dr Varun Gauri, finds that public servants are susceptible to confirmation bias. This is the tendency to favour evidence that supports our pre-existing beliefs. Another pervasive bias is framing effect, which explains how our decisions are based on the way information is presented, rather than the facts, such as statements that highlight positive or negative language. Banuri, Dercon, and Gauri show that there is a strong correlation between the political ideology of economists, who dominate key policy roles, and their policy decisions.

Research consistently shows that public servants draw on their prior beliefs when evaluating risky outcomes, especially when the topic is ‘ideologically charged.’ For example, when weighing up the effects of inequality, policymakers will oppose changes to minimum wage laws. Banuri, Dercon, and Gauri argue: ‘despite the fact that public institutions are designed to promote objective and impartial decision making, significant biases in decision making are evident.’

Group deliberation with experts from diverse fields can stop this bias. Significantly for sociologists, the researchers show that ‘social science training helps professionals interpret data accurately.’

Ideology and bias provide one piece of the puzzle. AI discourse uses gain framing, by focusing language on the possible — but untested — future rewards of AI technology. The negative effects of AI are therefore downplayed. AI discourse also plays into confirmation bias, focusing on nebulous economic growth, which public servants (especially economists) are primed to hear.

By reproducing gain framing of AI discourse, the Australian Government is at risk of optimism bias. This is the tendency to overestimate the likelihood of positive outcomes, while underestimating negative events. Optimism bias impacted weak state regulation that led to the 2008 global financial crisis, disaster planning, and other catastrophes.

Let’s now look at how AI discourse leverages the tactics that helped the mass media achieve political control in the past.

3. AI companies are manufacturing consent

Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky used the concept of ‘manufacturing consent’ to describe how mass media commandeered the political economy in the 20th Century. Consent in this sense refers to the political requirements used to create social order. Mass media did this through propaganda, established through the following business practices:

- Limiting ownership: a small number of corporations own multiple companies

- Loosening regulation: laws limiting market competition are weakened, and requirements to present factual and impartial content are minimised

- Lax conflict of interest rules: a small number of leaders who have common interests across many corporations, banking, investment firms, and government are appointed to influential boards overseeing the market

- ‘Diversification and geographic spread‘: Companies that dominated old media buy up new technology everywhere.

AI companies are following the same playbook, starting with ownership.

3.1. AI companies have limited ownership

In their recent quarterly reports, four of the world’s largest technology companies — Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet (Google) — have invested a collective $155 billion on their respective AI services. That’s more than the USA Government has spent on education, training, employment, and social services this year.

Microsoft owns a large share of the AI market. In January, Microsoft announced an $80 billion investment to expand its AI capability globally. Over two million companies worldwide use Microsoft 365, with the USA, UK, and Australia having the most users.

Many governments have exclusive contracts with Microsoft. In Australia, Microsoft’s seven-year contract increased tenfold this year to $954 million, specifically on the basis of Copilot, Microsoft’s generative AI chatbot.

Microsoft owns a majority share (49%) of OpenAI.

OpenAI owns ChatGPT. Microsoft has an exclusive partnership with ChatGPT, with an investment of USD$2 billion ($1 billion in 2019 and again in 2023).

AI consent is manufactured through this concentrated ownership of technology. A small number of USA-owned companies invest obscene amounts to dominate the market.

3.2. Governments are loosening AI regulation

Focusing on the economic gains of AI, the Commission announced that it is considering a text and data mining exception for the Australian Copyright Act. This would make it legal to train AI on copyrighted work.

The Commission’s Interim Report argues that, ‘AI-specific regulation should be a last resort.’ The Commission seeks to curtail proposed legislation to prevent ‘high-risk AI,’ such as generative AI. Instead, the Commission recommends ‘more flexible’ regulation to expand AI data access, as well making amendments to the Privacy Act 1988 that will lower standards, and remove the ‘right to erasure,’ which allows individuals to correct or remove their personal data held by organisations.

The Australian Society of Authors opposes the Commission’s copyright proposal. Their survey of 1,900 Australian authors finds that 12,000 Australian books have been stolen by Meta to train its generative AI tool.

Dr Alice Grundy, Visiting Fellow with the School of Literature, Language and Linguistics, at the Australian National University, argues that, ‘Creating greater leeway in Australian laws can be read as tacitly endorsing currently unlawful practices‘ (my emphasis).

Withdrawing copyright protections will decimate the creative arts workforce. This has a negative economic impact. The Australian book industry alone generates $2 billion annually for the Australian economy — revenue that AI is poaching. The State is currently allowing AI companies to engage in a ‘Robbing Peter to pay Paul’ trickery, by siphoning off economic productivity from the arts, in order to exaggerate AI output.

Gain framing focuses on data content (technology), rather than worker rights (people).

Deregulation is a key feature of how elites manufacture consent.

3.3. AI leaders have a conflict of interest

On the 12 August, Atlassian’s co-founder and ex-CEO (exited April 2024), Scott Farquhar, echoed the Commission’s stance on ABC News. He appeared in his relatively new capacity as Chair of the Tech Council of Australia, a peak industry organisation. In the exchange below, Farquhar deploys AI discourse, by focusing on AI supremacy, and establishing the interests of powerful groups above the rights of artists. Farquhar says that AI is ‘transformative’ three times in 20 minutes.

Scott Farquhar: So, what I’m saying is AI is a broad and transformative technology […] At the moment all AI usage of mining or searching or going across data is probably illegal under Australian law and I think that hurts a lot of investment of these companies in Australia. So, I think we should have a conversation about what we should have, what is fair use for these models […]

Sarah Ferguson [ABC journalist]: But right now, AI companies are just gobbling up all of that material for free. That’s what the artists are calling theft. Do you think that should stop?

Scott Farquhar: I think that the benefits of the large language models and so forth that we’ve got outweigh those issues. [My emphasis]

Here we see Farquhar deploys AI discourse to steer the conversation back to gain framing, rather than examining losses.

Farquhar evokes the ‘benefits’ of AI supremacy (they outweigh workers’ rights), but the benefits are reaped uniquely by elite technology firms. Farquhar has a net worth of USD$12.5 billion. He retains 20% share in Atlassian, which is valued at USD$43.05 billion, and he remains on its Board. He is participating in the Government’s Economic Reform Roundtable on 19-21 August. There is a conflict of interest in rich business owners being appointed to an influential board, and getting an audience with Treasury. This is another example of manufacturing consent.

Dr Terri Janke, a Wuthathi, Yadhaigana and Meriam woman, is a lawyer and intellectual property expert. Dr Janke tells ABC Radio National that she does not know how much consultation the federal government has done with First Peoples regarding the Roundtable. (I note that First Peoples are not on the Roundtable Agenda.) Dr Janke says that AI affects more than just the copyright of First Peoples. AI also impacts their heritage, Country, and cultural responsibility to nurture their living culture. She notes that AI models could have useful applications for First Peoples. However, AI policies are speeding ahead without empowering First Peoples to shape regulation and develop the technology.

Additionally, Dr Janke fears that AI may be absorbing incorrect information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, as well as sacred knowledge that may have been published without First Peoples’ informed consent.

The Commission’s Interim Report has no discussion of Indigenous Data Sovereignty. There is only one brief mention of First Peoples (a reference to an ABC news story about park rangers using AI to detect Aboriginal rock art).

This raises another aspect of AI discourse – limiting what is possible, by ignoring First Peoples.

3.4. AI companies rely on diversification and geographic spread

Microsoft is facing an antitrust lawsuit in the European Union for bundling chat and video features into Teams as part of its 365 features. Microsoft has been accused of creating an illegal monopoly in the USA, by offering ‘free’ cybersecurity features for government clients, to drive up reliance in its products.

These examples of demonstrate how AI companies are practicing market cannibalism. ‘Market cannibalisation’ describes when a new product (in this case, AI) takes over a market through an older product from the same company. AI is a trojan horse placed into existing services (such as Copilot AI in Microsoft 365) to increase subscription prices, steal customer data, and stifle competition.

Market cannibalisation allows AI companies to diversify their services across multiple markets. This is another way in which AI companies are manufacturing consent, at a global scale.

4. AI discourse maintains corporate power

Throughout this analysis, I have explored four ways in which AI discourse promotes technological supremacy. This discourse serves the interests of elite groups, primarily wealthy technology leaders.

4.1. AI discourse is used to market technological supremacy

In The Birth of the Clinic, Foucault established that a discourse is the way in which language is structured and used to establish a specific way of talking, thinking, and justifying assumptions about the world.

AI companies market the idea that automation is superior to the work of humans. AI discourse presents the future potential of AI as being ‘transformative,’ exclusively in relation to economic gains. The discourse underplays potential losses.

By reproducing AI discourse, the Australian Government is currently replicating various behavioural biases. This undervalues the known social, cultural, and economic contributions of artists and First Peoples.

4.2. AI discourse relies on selective use of science

Foucault argues that discourses classify observations about social phenomena in ways that align with institutions of power.

AI discourse deploys the language of science to make corporate interests seem normal, natural, true, and logical.

The Australian Government uses a theoretical model of AI task-based estimates. The State obscures the lack of empirical testing of their economic projections.

Ultimately, a skewed use of science supports the limited ownership of AI companies, and furthers manufactured consent.

4.3. AI discourse seeks to eliminate competition

In The Archaeology of Knowledge, Foucault illustrates that discourses establish new possibilities, informed by hidden assumptions.

AI discourse promotes innovation in order to maintain social control. AI companies talk about their data needs as a benefit. This distracts from their use of market cannibalisation to gain greater ownership.

The loosening of regulation reinforces AI discourse, by considering theft of the arts as ‘fair use.’ The underlying belief is that the labour of Australian creative workers are less important than the demands of overseas conglomerates.

4.4. AI discourse hides the true costs of automation

Foucault shows that discourses establish strategic choices about how issues, behaviours, and experiences are spoken about, as well as what remains unsaid. Discourses therefore suppress alternatives that do not conform to the interests of those in power.

AI discourse conceals the negative environmental costs of this technology. Additionally, AI discourse ignores race and colonisation, despite AI impinging on Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property.

The State meets with AI elites, while excluding First Peoples from decision-making.

Seen through a sociological lens, AI discourse inflates the economic power of corporations, over the rights of individual workers and First Peoples.

5. What’s next

Economic models estimate the potential growth of AI, without empirical evidence. There is a focus on AI’s unproven benefits, but not on its harms. This plays into the biases of policy-makers, whose decisions are influenced by confirmation bias, gain framing, and optimism bias.

AI companies manufacture consent by monopolising the market, deregulation, taking a vested interest in governance boards and processes, and diversifying its product through market cannibalisation.

By creating a discourse of AI supremacy, AI companies hope to further dominate the market, and marginalise their competition.

AI may have many benefits, however, policy would be improved by taking a critical view of AI discourse. Insights from a broader groups of experts, led by First Peoples, would support a better approach to regulation. The rights of artists and First Peoples must remain a priority.

In the next post in the Sociology of AI series, I analyse how AI impacts the future of work.

Learn More

Discover more from The Other Sociologist

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.