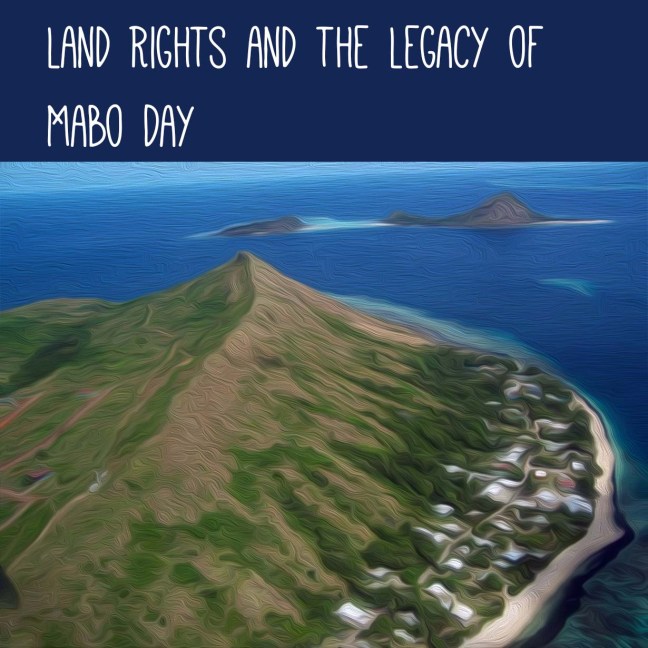

I write this as a reflection at the end of Mabo Day, marking the end of Reconciliation Week. This day commemorates the 3 June 1992 High Court ruling that recognises Native Title – land rights of the Meriam people of the Mer Islands of the Torres Strait, which opened land rights for First Nations across Australia.

On 20 May 1982, Eddie Mabo, Sam and David Passi, Celuia Mapo Salee, and James Rice lodged their land claim. The case took a decade to finalise and addressed multiple legal injustices, including the myth of terra nullius (that Australian land was unowned before colonisation), recognition of Native Title and cultural definitions of land rights, and establishing the Native Title Act.

Today’s post covers the ongoing impact and challenges flowing from the Mabo case, and the sociological issues it raises. In paricular, non-Indigenous people’s narrow awarenes about the cultural significance of land.

Myth of terra nullius

The Mabo case overturned precedence of “terra nullius” (meaning “no one’s land”). The Commonwealth’s claim to land in 1788 was established under the false premise that Australia had not been lawfully settled before British invasion. The case successfully proved that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people had pre-existing laws governing the use and enjoyment of their land. The case additionally chronicled that terra nullius was founded on racial discrimination and false understandings of culture and land rights.

Native Title

The case demonstrated that Meriam people had prior rights due to long-standing customs and laws that pre-existed colonisation. These practices are fundamental to their “traditional system of ownership and underpin their traditional rights and obligations in relation to land.” This hinges on establishing continuous use of the land. This is difficult to evidence when colonisation involved genocide of First Nations people as well as forced dispossession of their land. However, the Mabo case presented evidence of intricate knowledge of traditional fishing in coral reefs and large stone fish traps.

The Native Title Act 1993

This opened Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s claims to their traditional land rights and compensation. The Act recognises land rights for “living, traditional purposes, hunting or fishing and/or to teach laws and customs on the land.” The Act also established new standards and mechanisms to make land claims, and superseded past Acts.

There have been 496 Native Title deliberations since the Mabo case. Approximately 37% of Australian land and waters are covered by Native Title, plus there are over 600 registered Indigenous Land Use Agreements (voluntary agreement stipulating use of land and water between Native Title holders and other people).

Ongoing legacy

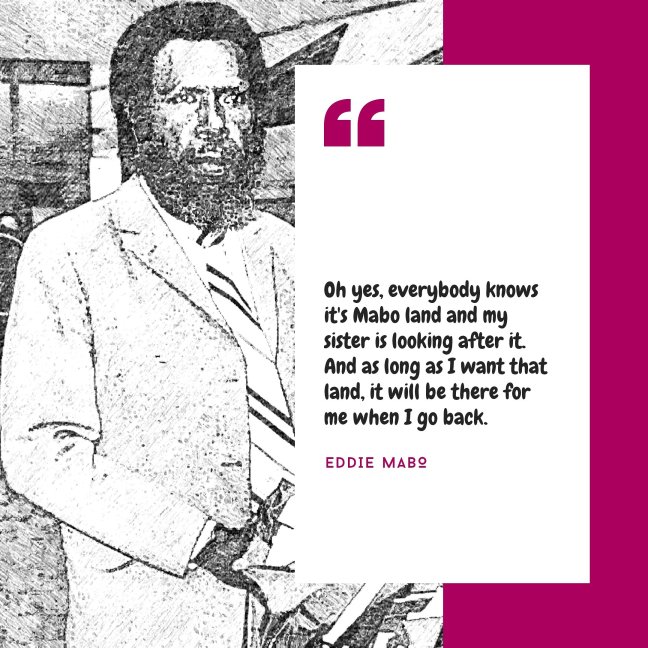

Eddie Mabo died of lung cancer on 21st January 1991, so he did not see the High Court ruling and the precedence it set. His legacy remains strong, with his family remaining politically engaged to the present day, including his wife Bonita Mabo AO (died 2018), daughter Gail Mabo, and his granddaughter, Boneta-Marie Mabo.

Native Title is an ongoing legal issue, with many claims held up in courts for many years. Threshold for evidence has become harsher, with groups having trouble establishing evidence of uninterrupted use of land due to colonialism. Inadvertently, the Mabo case also extinguished certain powers, which now makes it trickier for Aboriginal groups along the urban East Coast, where development has complicated matters (see also the Wik Decision 1996 on statutory leases).

Patricia Lane, the first registrar of the National Native Title Tribunal from 1994-1997, says State Governments have been generally poor at negotiation, especially in minerals-rich areas like Western Australia. In Tasmania, 1% of land was returned to Native Title owners from 1995-2005, but in the past 15 years no further land claims have been successfully recognised.

Still, First Nations people continue to fight. Recently, the Native Title rights of Yindjibarndi people in Western Australia’s Pilbara region retained their exclusive rights to over 2,700 square kilometres of their land, including the Solomon mine. The High Court dismissed the Fortescue Metals Group’s appeal, meaning it has lost control of its Solomon iron ore mine.

The federal Government’s National Indigenous Australians Agency estimates that 60% of land will be returned to traditional owners once all current cases are finalised.

Sociological impact

The Mabo Decision was a momentous event, forcing Australia’s legal system to acknowledge, and begin to rectify, our colonial history.

At the same time, the Mabo Case raises ongoing sociological issues about non-Indigenous Australia’s failure to progress land rights.

Colonial processes are still used to aim to redress colonialisation

The legal system uses Western concepts of proof that make little sense given our colonial history. Despite historical records showing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were decimated or forced off their land under the Frontier Wars, states still require proof of pre-colonial continuous use of land

Many non-Indigenous Australians do not understand land rights

States see Native Title as an encroachment of their governance. To our collective detriment, we fail to recognise that Native Title holders have demonstrated their excellence in land management for thousands of years. For example, in sophisticated agrarian traditions and cultural burnings. This knowledge would help to increase sustainable land management, especially given recent bushfire crises and climate change. Native Title owners also invest in a mixture of business arrangements, expanding culturally appropriate development and conservation opportunities. State opposition to timely resolution of Native Title reflects outdated capitalist models that have proven detrimental.

Native title compensation could address part of the impact of intergenerational trauma

Nothing can erase the ongoing suffering of the Stolen Generations, but reparations and Native Title compensation would begin to address the impact. By removing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people at the time of colonialism, they were denied their language, culture, spirituality and connection to Country. Additionally, not having land rights has meant that First Nations people were actively denied the ability to acquire wealth. Together with laws that denied education and access to social services, it’s clear that land rights is one path to healing this trauma and improving health and socio-economic opportunities.

Non-Indigenous use and enjoyment of land needs rethinking

The Mabo Case established legal recognition of cultural significance of place to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This is something that non-Indigenous people do not value enough. Watch below, as Professor Aileen Moreton-Robinson, Goenpul woman of the Quandamooka nation on Stradbroke Island in Queensland, discusses how tourist enjoyment of Lake Burmeer differs from her grandmother and her mob. Prof Moreton-Robinson is also a sociologist. She explains that land is sacred and alive, but non-Indigenous Australians do not share the same view. We might then see, in turn, how this discrepency continues to diminish both sustainability and land rights.

References

Allam, L. (2020) ‘Right fire for right future: how cultural burning can protect Australia from catastrophic blazes,’ The Guardian, 19 January. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/jan/19/right-fire-for-right-future-how-cultural-burning-can-protect-australia-from-catastrophic-blazes

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies [AIATSIS] (2011) Case summary: Wik Peoples v Queensland. Online resource Last accessed 3 June 2020: https://aiatsis.gov.au/publications/products/case-summary-wik-peoples-v-queensland

AIATSIS (2019) Mabo Case. Online resource. Last accessed 3 June 2020: https://bit.ly/mabo-case

Australian Government (1993) Native Title Act 1993. Last accessed 3 June 2020: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2019C00054

Baker, N. and Maunder, S. (2020) ’28 years since Australia’s historic Mabo decision, ‘there is a lot of unfinished business,”‘ SBS News, 3 June. Last accessed 3 June 2020: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/28-years-since-australia-s-historic-mabo-decision-there-is-a-lot-of-unfinished-business

Deadly Story (Nd) Uncle Koiki Mabo Launches Legal Case for his Land. Online resource. Last accessed 3 June 2020: https://www.deadlystory.com/page/culture/history/Uncle_Koiki_Mabo_launches_legal_case_to_recognise_Aboriginal_and_Torres_Strait_Islander_rights_to_land

Jenkins, K. (2020) ‘Yindjibarndi people celebrate the end of long battle with Fortescue over Native Title rights,’ SBS News, 29 May. Last accessed 3 June 2020: https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2020/05/29/yindjibarndi-people-celebrate-end-long-battle-fortescue-over-native-title-rights1

May, C. (2017) ‘Making Mabo: How has Native Title changed since the landmark ruling?,’ Pursuit, 2 June. Last accessed 3 June 2020: https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/marking-mabo-how-has-native-title-changed-since-the-landmark-ruling

Pascoe, B. (2014) Dark Emu. Broome: Magabala Books.

Screen Australia Digital Learning (2015) ‘Sea rights,’ Mabo: The Native Title Revolution. Online resource. Last accessed 3 June 2020: https://www.mabonativetitle.com/mabo_09.shtml

University of Sydney (2017) Five Things You Should Know About the Mabo Decision. 2 June. Online resource. Last accessed 3 June 2020: https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2017/06/02/five-things-you-should-know-about-the-mabo-decision.html