Despite dire predictions, researchers forecast that few industries will lose a substantial number of jobs due to artificial intelligence (AI). Instead, AI is more likely to alter the way humans work. The AI industry may also create new roles, but this may amplify inequality. In this third post in my Sociology of AI series, I explore the perceived impact of AI on jobs, and the stratification that may follow increased automation of the labour market. I analyse evolving policy directions, including a new report by Jobs and Skills Australia, on AI-related job losses. I then review sociological understandings of AI and work, and recent examples of job redundancies. I analyse a much-publicised study by Microsoft, which claims AI can replace 40 professions, including translators, historians, artists, and customer service workers. This case study shows that AI companies distort evidence to overstate the functions, utility, and accuracy of AI technology. I argue that AI discourse hinges on eliminating competition from human professionals. Sociology uncovers the ways in which scientific models and customer data are used to make unethical and spurious claims.

Summary

- This article looks at the ways artificial intelligence (AI) impacts the labour market. This means how power relations impact work patterns and opportunities

- The Australian Government has struck a deal with AI companies and the trade union. AI companies will pay for copyrighted work, but we don’t know the details

- The Government has released a new study. It says that some jobs will be lost because of AI, but many more jobs will be changed for the better. The study has many problems. It uses a theory of how AI models think they can do human jobs. The study has used AI to do its analysis. It uses old information

- The study says automation will hurt First Peoples. It has no recommendations about how to stop this

- The study has many biases. It prefers to look at the possible benefits of AI, but it does not consider what might go wrong

- AI is starting to have a negative effect on some workers. New graduates are afraid that AI will take over many jobs. Sociology finds that few jobs will be fully automated

- Big companies are cutting customer service jobs. They say AI can do this work more effectively

- A recent example shows that AI creates more work after human workers are fired

- AI is unlikely to replace jobs that focus on human interaction. For example, teaching, healthcare, and making decisions

- Instead, AI may change the way we work. It will also create new jobs. This might lead to greater inequality in some industries

- A popular study by Microsoft says that AI will replace 40 professions. The study has many gaps. It relies on anonymous customer questions to an AI chatbot. The study doesn’t include demographic information about these customers

- The study covers a small list of tasks. It does not test real outcomes. It does not follow ethical guidelines

- Microsoft’s research shows that users are unsatisfied with AI analysis, art design, and advice. These are the human skills that Microsoft claims AI will make obsolete. This is an example of how AI claims are over-stated

- Research shows that AI is often wrong. This is hidden from customers

- AI discourse wants us to believe that AI is greater than human workers. To convince us, AI companies use poor science measures. They take advantage of political problems to get more power.

1. Introduction: Sociology of AI and the labour market

This is the third instalment of the Sociology of AI series. Part 1 outlined the Sociology of Artificial Intelligence, focusing on ethics, race, and inequality. Part 2 provided an analysis of Artificial Intelligence and the Economy. I used the analytical framework by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky on manufacturing consent. I showed how AI companies are attempting to commandeer the political economy using the tactics of mass media conglomerates. By monopolising the market, deregulation, influence on important boards, and diversification, AI corporations push propaganda to make AI technology appear ubiquitous. The goal is to make AI ‘transformation’ seem inevitable. I drew on the theory of discourse by Michel Foucault (1963) and (1969). I outlined how AI companies have created a discourse of technological supremacy; that is, automation is presumed superior to human labour.

Today, we’ll look at how AI discourse is used to reshape the labour market. Sociology Professors, Arne L. Kalleberg and Aage B. Sørensen, define the labour market in relation to the institutions, practices, and laws that impact work. That is, the social context in which ‘workers exchange their labour power in return for wages, status, and other job rewards.’ Kalleberg and Sørensen argue that the rules that govern our working conditions, training, and job skills are not neutral. They are shaped by structural forces and relationships of power, which lead to inequality.

My analysis will show the institutional forces manufacturing consent for AI at work, and the influence of AI discourse on labour force policies.

Section 2 explores the future direction of government policy for the creative industry, and broader job losses.

Section 3 sketches sociological research on worker perceptions of AI, and recent examples of job cuts that are justified through AI discourse.

Section 4 presents a case study of a Microsoft report, showing how science is used to justify AI propaganda.

Section 5 draws together my analysis, on how AI discourse impacts work.

Let’s begin by looking at the changing policy landscape.

2. AI discourse is shaping labour policies

On 21 August 2025, following the Economic Reform Roundtable led by Treasury, the Australian Government, the Tech Council of Australia (led by Scott Farquhar), and the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU, led by Secretary Sally McManus) have agreed to a proposal of, ‘properly paying creatives, journalists and academics for their work’ (my emphasis). The details are yet to be designed.

This progress is potentially promising, however, AI corporate lobbying is mediating policy outcomes, while other stakeholders, such as First Peoples and the creative industry, are not part of these negotiations. Giving a billionaire a seat at the policy table over other stakeholders is a marker of manufacturing consent, through conflict of interest.

Additionally, while the state conducts further analysis, AI companies continue to poach copyrighted materials and customer data.

2.1. Government predictions on job losses rely on flawed methods

On 14 August 2025, Jobs and Skills Australia (JSA), a federal government agency, released a report, Our Gen AI Transition. The report argues that many jobs in the future will be augmented by AI. The headline results reported by media focus on AI stealing human jobs. However, JSA’s methods do not support their conclusion. In Part 2 of the Sociology of AI, I showed how the Productivity Commission has used a theoretical model of AI’s economic potential, based on the work of Turkish-American economist, Professor Daron Acemoglu, leading to flawed conclusions. JSA’s report also relies on an earlier paper by Professor Acemoglu and colleagues. The JSA report proves to be another example of how AI discourse relies on selective use of science to influence social policy.

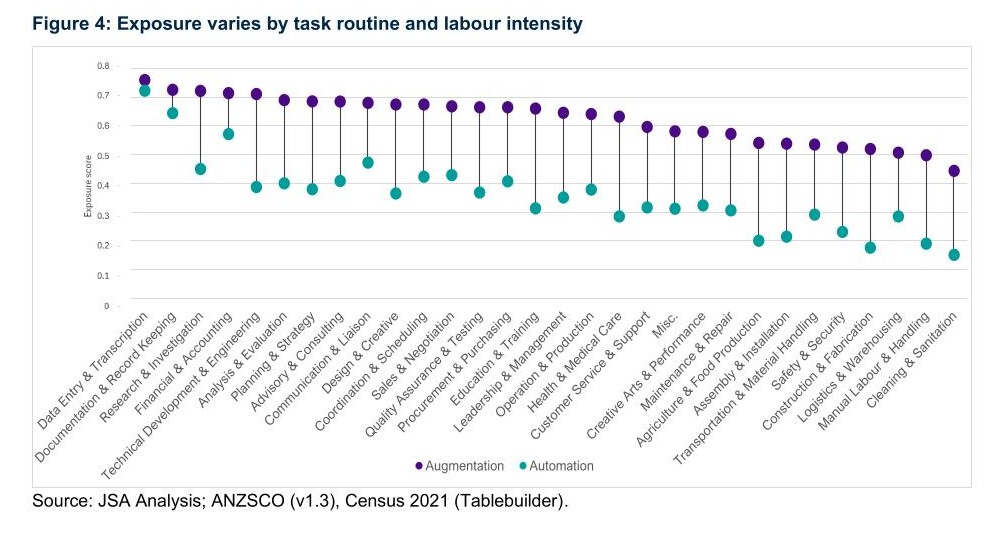

JSA has measured the potential exposure to AI and ‘a theoretical indication of occupational change’ (my emphasis). The study generates quantitative scores of AI augmentation, which are applied to Australian job classifications.

JSA conducted extensive consultations on industry perceptions of AI, however, the JSA report has used AI to ‘support analysis,’ with human oversight. This raises questions about data interpretation and ethics. This is especially concerning given high rate of errors of AI, including fabricating citations, inaccuracy, and various other problems related to AI ‘hallucinations‘ (the tendency for AI to invent facts to fill in gaps).

JSA uses the conceptual framework proposed by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), a United Nations agency. The ILO’s 2024 study, ‘Generative AI and Jobs,’ relies on ChatGPT4 to rate its own capacity to carry out tasks in various industries (see Box 1 below). The ILO, and by extension, the JSA, measures how AI thinks AI can do human jobs. This is a biased measure, given that AI is often ‘confidently wrong.’

Box 1: JSA methods and issues

- The ILO researchers gave ChatGPT-4 a list of jobs, and then asked the AI to give a 100-word definition of the job

- ChatGPT was then asked to generate a list of tasks for these jobs, and to give each job and task a score of potential automation

- A key assumption is that AI has already scraped public sources, including the ILO’s works, and that its descriptions are accurate

- The study presents case studies of how AI may be used in different industries. This is based ’80 to 100 hours’ of in-depth interviews, a survey (sample and measures not stated), 30 in-depth interviews and seven focus groups with workers on experiences with generative AI in their jobs (unclear if this is part of the 100 hours), consultation with 12 technical and clinical experts about the study’s scope, and 200 formal submissions on AI adoption

- JSA used AI to support quantitative and qualitative analysis, as well as editing. Ethics considerations are not discussed, including data protections, and the fact that AI models do not simply summarise materials, but are designed to generate new content.

2.1.1. Estimated job losses use outdated sources

To measure the potential job losses due to AI augmentation, JSA draws on an outdated list of occupations from 2013 (for details, see Box 2). JSA appears to be using outdated data, which may undercount potential job losses. Nevertheless, the JSA’s calculations suggest that the five roles which may ‘lose the most employment’ are:

- General clerks

- Receptionists

- Accounting clerks and bookkeepers

- Sales, marketing and public relations professionals

- Business and systems analysts, and programmers.

According to JSA, the five industries facing the highest employment loses are:

- Retail trade

- Public administration and safety

- Financial and insurance services

- Professional, scientific and technical

- Rental, hiring and real estate.

Box 2: Occupations and industry classification issues with JSA study

- JSA draws on the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations, Version 1.3, from 2013

- The current list is the Occupation Standard Classification for Australia (OSCA), 2024, Version 1.0

- The 2024 OSCA classification reflects that the industries measured by the JSA have significantly changed since 2013. However, the JSA seems not to have accounted for these changes. For example:

- Sales is now classified as Sales and Marketing (under Business Administration Managers)

- Public relations now fall under Communications

- Business and systems analysts and programmers are now under ICT Business and Systems Analysts and Architects

- We might presume JSA used the Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification list for their analysis, though this is not stated, as data sources are not cited.

2.1.2. Policy predicts high job augmentation

Other than administrative, sales, and business analyst job losses, JSA argues that AI is more likely to augment the way we work in the future. That is, most jobs will have higher automation. Based on level of exposure to AI, JSA sees that three tasks have high potential for AI augmentation: data entry and transcription, documentation and record-keeping, and research and investigation.

2.1.3. AI discourse hides the costs of automation on First Peoples

JSA argues that AI presents many challenges to First Peoples. This includes not being engaged in developing AI technologies and poor Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property protections. JSA offers limited policy solutions for how to redress this, other than suggesting that First Peoples receive greater AI training, and that AI companies participate in job fairs. These two suggestions do not address structural racism in AI and resourcing First Peoples’ leadership.

Additionally, JSA suggests that AI must apply ‘Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination.’ This is an important suggestion, but JSA has not considered this further. JSA makes 10 policy recommendations, and none focus on First Peoples.

JSA might have recommended implementing the 10-year vision statement of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander AI Futures Communique.

2.1.4. AI discourse is biased

As I’ve previously shown, AI discourse plays into social policy biases. The JSA follows suit, by giving greater weight to the future gains of AI (gain framing), ignoring the limitations of AI-task measurements (confirmation bias), and underestimating how AI corporate lobbing is inflating AI productivity (optimism bias). See Table 1 below for further detail.

The JSA is focused on one hypothetical economic possibility. This ignores scientific evidence that 95% of AI companies fail to generate a return on investment.

Table 1: AI policy bias in the JSA report

| Policy bias | Definition | Example from JSA analysis |

| Gain framing | Decisions are based on the way information is presented, rather than the facts. For example, being swayed by language that highlights positive outcomes, while ignoring potential losses | Giving greater weight to the unproven future gains of AI. JSA uses a theoretical model that measures how AI describes job tasks. This model has not been empirically tested. JSA applies this model to outdated Australian job categories. The model writes off job losses in several industries, and commits little effort to address economic losses to First Peoples |

| Confirmation bias | Interpreting new evidence to affirm pre-existing beliefs | Relying on untested projections of economic growth. JSA favours economic modelling that mirrors principles of economic rationalism. JSA uses AI-assisted analysis, while ignoring empirical evidence on the high rate of error in AI |

| Optimism bias | Overestimating the likelihood of positive outcomes, while underestimating negative events | Overvaluing the extent to which AI job augmentation will increase economic growth. JSA underestimates how AI discourse inflates AI productivity. JSA does not address potential future issues, such as an economic crash due to overinvestment on AI with little returns |

AI discourse has influenced government policies to take AI job augmentation as a given, despite limited evidence. This seems to be having an impact on workers.

3. AI is negatively impacting workers

We now turn to a sociological study on worker expectations of AI, before exploring recent examples of AI-related job cuts.

3.1. Workers expect that AI will adapt their jobs

A sociological study explores changing attitudes towards AI and work. Associate Professor Paul Glavin, of McMaster University, Professor Scott Schieman, and Alexander Wilson, both from the University of Toronto, surveyed Canadian workers from September 2023 to April 2025. In the last six months, workers’ concern that vast aspects of their jobs will be taken by AI has risen from 17% to 23%, a spike driven by recent graduates. The researchers note that only 9% of workers expect their jobs will be completely automated. Instead, the majority of workers expect AI will adapt the way they work.

Glavin, Schieman, and Wilson note that AI that is likely to create new jobs, however, this may increase inequality.

‘AI will undoubtedly create new roles and opportunities, particularly where human judgment remains essential. But we shouldn’t assume this future will preserve job quality. The story of retail banking offers a sobering lesson: automation first increased the number of teller jobs – but didn’t raise pay. Ultimately, tellers weren’t replaced by machines but by digital banking, shifting many to call centre jobs with less autonomy and lower wages. Even in the absence of widespread job displacement, AI may follow a similar pattern –reshaping many jobs in ways that reduce discretion, increase surveillance and erode its overall value.’

Sociology Professor, Allison Pugh, sees that AI cannot replace jobs that rely on social interaction skills, which she calls ‘connective labour.’ For example, supporting learning and skills development, specialist advice, or informing complex decisions.

While this sociological evidence suggests most jobs will be safe from full automation, recent redundancies in customer service have been justified through AI.

3.2 Companies use AI as an excuse to cut customer service jobs

On 29 July 2025, the Commonwealth Bank replaced 45 customer service jobs with an AI chatbot. On 30 July, software company Atlassian cut 150 customer service jobs to expand its AI capability. On the same day, Atlassian’s co-founder and current board member, Scott Farquhar gave a National Press Club speech imploring Australia to invest in more AI data centres.

These layoff announcements coincide with the ACTU advocacy for enforceable agreements on the use of AI, to protect workers.

On 21 August, the Commonwealth Bank was forced to reverse its decision and reinstate the jobs cut three weeks ago, following a dispute at the Fair Work Commission. The Finance Sector Union (FSU) found that customer service work at the Bank increased heavily after the bot was introduced. The FSU said: ‘Call volumes were rising, with management scrambling to offer overtime and even pulling team leaders onto the phones.’

‘Using AI as a cover for slashing secure jobs is a cynical cost-cutting exercise, and workers know it.’

– Julia Angrisano – FSU National Secretary (2025)

Union advocacy has staved off further job losses, however, as we have seen, AI companies continue to lobby for social policy changes that are unfavourable to workers.

In the following case study, I demonstrate various issues with the way AI companies manufacture consent through job loss propaganda.

4. Case study: AI discourse uses science selectively

On 29 July 2025, a study by Microsoft gained strong media interest. Typical headlines, such as, ’40 jobs most at risk from AI,’ ‘The jobs that may be replaced by AI,’ and ‘Which jobs are AI-safe?’, have been covered by Fortune, Newsweek, Yahoo News, Business Insider, INC, Gizmodo, The Sun, and more.

I now provide an analysis of Microsoft’s research, focusing on four issues: skewed methods and data, limited analysis of AI impact on occupational functions, poor outcome measures, and lack of research ethics discussion. This case study demonstrates a broader pattern of AI discourse: the selective use of science.

4.1. AI discourse relies on skewed methods and data

Microsoft’s study, ‘Working with AI: Measuring the Occupational Implications of Generative AI’ (henceforth, ‘the study’), is published on arXiv, an open-source archive. The paper is not peer-reviewed.

The study reports on approximately 100,000 customer interactions with Bing Copilot, the AI chatbot integrated across Microsoft 365 products, including Word, Teams, and Outlook.

The study uses ‘thumbs-up’ and ‘thumbs-down’ reactions from customers in Copilot as a proxy for user satisfaction with AI advice. The study measures customer queries, tasks completed by Copilot, and an extrapolation of the occupations that might have high and low AI ‘applicability.’ See Box 3 for further detail.

Box 3: Summary of methods in Microsoft’s Copilot study

- Copilot is a generative AI tool. This is a set of algorithms that draw on existing data to create new content

- Copilot uses large language models (LLMs), which are trained on massive amounts of text. Microsoft says its AI is trained on ‘de-identified data from Bing searches, MSN activity, Copilot conversations, and ad interactions’ (my emphasis). Microsoft’s study is therefore measuring Copilot chats that have been, in part, informed by a broader set of Copilot chats.

- Recursive data in AI is a problem, but the Microsoft study seems not to have controlled for this issue.

- The study measures user goals (AI search queries by human customers) against AI action (the activity performed by the AI following a query). The researchers classify queries under a list of work activities (e.g. getting information, selling or influencing others), and occupations (e.g. political scientists, mathematicians)

- The study lists the 40 occupations with the highest AI applicability scores, as well as the 40 occupations with the lowest scores. AI applicability ‘captures if there is nontrivial AI usage that successfully completes activities corresponding to significant portions of an occupation’s tasks’ (my emphasis). This is measured as the highest work activities with high completion rates by the AI chatbot

- On 21 August, the researchers offered a brief qualification about their study. This does not address the key limitations of the paper.

There are several sampling and methodological issues with the study:

- There is no demographic analysis of the sample. We do not know how socioeconomics affect AI engagement. See Box 4 for some examples

- There is no control group. We do not know if people who choose to use Copilot get better work outcomes than people who do not rely on Copilot

- We do not know how AI feedback impacts implementation and outcomes. The study acknowledges that the ‘thumbs’ feedback is limited to people who chose to give this feedback. We do not have a clear breakdown of positive versus negative feedback for different actions and work activities. We do not know how this feedback correlates with worker outcomes. For example, did positive feedback always lead to users accepting and implementing the AI suggestions? Do people give negative feedback after checking the information, rejecting it because it is incorrect?

There is a well-evidenced difference between intentions and actions (known as the intention-action gap). Asking an AI chatbot for information does not mean this information will be used, nor that the information is able to be actioned. It does not tell us whether this advice is effective.

Box 4: Demographics and user patterns that may impact Microsoft’s Copilot study

- Socioeconomics: We do not know whether age, gender, race, education, disability, occupation, or other factors impact on AI queries, satisfaction, and continued use of Copilot.

- Frequency: We do not have a breakdown of queries and tasks. For example, we do not know if 100,000 individuals made one query each, or if one person made 100,000 separate queries. We do not know if some subgroups of people are more likely to make some query types (e.g. information) more often than other types of queries (e.g. sales advice).

- Drop-off rates: We do not know if people make one query once, and then never again. We do not know why drop-off may occur. E.g. Copilot failed to meaningfully assist the customer. We do not know if there are backfire effects correlated with drop-off. E.g. Work assisted by AI is poorly received by clients

- Self-efficacy: We do not know if professionals or experts are less likely to use Copilot than novices. We do not know whether people perform their jobs better after using Copilot. We do not know whether the people making queries fully accept, partially accept, or reject the AI’s information. We do not know how much users may supplement AI information with prior knowledge, or other sources.

4.2. AI discourse obscures functional limitations

The study is limited by the types of functions Copilot can perform. According to Microsoft, Copilot can search and retrieve information, and carry out low-level administrative tasks. The study measures whether the AI performs a task (i.e. whether the AI gives an answer), but it does not measure whether the tasks are measurably useful and correct. For example, how much time is meaningfully saved by the AI versus human labour, taking into consideration checking the AI’s facts, citations, and other inaccuracies?

This study raises issues of validity; this refers to the research design and instruments accurately measuring the stated aims of the study. To measure ‘AI applicability’ to different occupations, we would need:

- A comprehensive list of tasks undertaken in these professions. These tasks then need to be measured against the tasks and outcomes performed by AI

- An evaluation of the accuracy and quality of the tasks completed by AI. This would require a representative sample of experts from each occupation.

4.3. AI discourse does not measure customer outcomes

Microsoft users who gave feedback were most positive about writing assistance, editing, information retrieval (‘researching’), and purchasing information. They were less satisfied with AI advice about specialist expertise, especially data analysis and visual design. Users are also dissatisfied when ‘the AI tries to directly provide support or advice.’

Chatbot queries are a poor measure of whether tasks can be meaningfully replaced by AI. To make this comparison, the study would need:

- Randomised control experiment: For example, some participants perform their jobs with AI and others without AI

- Stronger sample design: weighting, stratified randomisation, and other controls are needed to ensure the sample reflects the diversity of users

- Behavioural measures: self-reported satisfaction with the AI chatbot’s answers (the ‘thumbs’ feature), is a limited measure. More meaningful outcome include implementation of AI advice (to measure whether AI can replace human expertise), plus behavioural change (to test whether AI improves work outcomes). See Table 2 for some examples.

Table 2: Examples of potential behavioural measures of AI queries

| Work activities and occupations analysed in Microsoft study(1) | Potential behavioural outcome measures |

| Top 3 most frequent generalised work activities in Copilot usage according to Microsoft (Figure 2, p.7) | |

| Getting information | Factual information is implemented in business case that is approved by executives |

| Communicating with people outside the organisation | Meeting attendees understand key points and next actions |

| Performing for or working directly with the public | Increased number of vulnerable customers signup to agency’s programs |

| Top 3 occupations with highest AI applicability score according to Microsoft (Table 3, p.12) | |

| Interpreters and Translators | Translated text improves non-English speakers’ access to government services, healthcare, and legal advice |

| Historians | Government reports and public inquiries incorporate accurate historical advice |

| Passenger Attendants | Advice to enhance rail network improves passenger safety and aligns with regulations |

4.4. AI discourse has an inadequate focus on ethics

The Microsoft study has a footnote that seems to be an internal ethics approval (cited as Microsoft IRB#11028), but the paper lacks discussion of research ethics.

In the USA, and elsewhere, research must follow regulations and guidelines. In the USA, behavioural research involving human participants, must follow ethical principles. People must be able to give informed consent, or have the choice to opt out of research.

Copilot is a new product that is difficult to opt out of. Users must open each Microsoft 365 app and navigate a series of steps to turn off Copilot in each service, but you cannot remove it easily. Copilot was forced on consumers, with a hefty price hike. This is an example of manufacturing consent through diversification.

In March 2025, Microsoft refused to address the UK Government’s questions on lack of consent to its AI services.

As presented, it appears Microsoft is using private customer data without allowing people to opt out of the published study. Anonymisation is one requirement of ethical processes, but deidentified data still require informed consent. A generic tick box during installation of Microsoft 365 (e.g. Microsoft Services Agreement) also does not constitute adequate informed consent for published research.

How many of these customers would consent to giving their data if they knew this meant potentially downsizing 8,468,350 jobs with AI? (Data drawn from Table 3 of the Microsoft study.)

Research ethics is doubly pertinent, given the hostile political climate that is cutting funds to the arts, sciences, humanities, universities, libraries, museums and other not-for-profits in the USA, and similar cuts to the arts and humanities in Australia, and elsewhere.

By focusing on AI applicability to existing jobs, AI companies ignore other systematic effects. This is an example of optimism bias, where a belief on assured success underestimates the likelihood of failure. Specifically, how AI seeks to weaken key industries that support creativity, public education, and social progress.

This case study has shown that AI discourse aggrandises technological supremacy. Science is used as propaganda, feeding the media stories that advance AI discourse. See Box 5 for a summary of how this practice aligns with manufacturing consent.

The next section reviews the various examples I’ve discussed, to highlight how AI discourse seeks to manipulate the labour force.

Box 5: Microsoft as an example of how AI corporations manufacture consent

Microsoft’s AI strategy mirrors the tactics used by old media companies.

- Limited ownership: a small number of companies own a large share of the market. As I’ve previously shown, Microsoft owns a majority share of OpenAI, and it has an exclusive partnership with ChatGPT.

- Loosening regulation: AI companies drive down competition by generating media propaganda. Microsoft’s study is designed to increase worker anxiety and magnify the perception of AI technological supremacy across multiple industries.

- Conflict of interest: Over two million companies use Microsoft 365, which includes its AI chatbot, Copilot, as a core feature. This AI tool is forced on influential policymakers, through Microsoft’s lucrative, multi-year government contracts. Public servants have mass exposure to AI through their everyday work on Microsoft products, creating the illusion that AI is pervasive and inescapable. This is known as mere exposure effect, which describes how individuals develop preferences through repeated exposure and familiarity. AI leaders have an easier time pushing their industry agenda with government when they can cite research by Microsoft, a product that is preloaded on government laptops.

- Diversification and geographic spread: Microsoft has implemented Copilot (a new product) across all of its previous services to increase subscription prices, steal customer data, and stifle competition (a tactic known as ‘market cannibalism’). Customer data is then used in Microsoft’s study, to sell the idea that AI can outperform humans. This is meant to drive up demand for AI, even as this industry is failing to meet its economic promise.

5. AI discourse consolidates power through the labour market

I’ve previously shown that AI discourse maintains the economic power of elite groups. My analysis here has shown that AI discourse consolidates power, by influencing labour market processes.

- AI discourse is used to market technological supremacy: AI discourse is laden with bias. JSA uses an AI model which reproduces ideas from economic rationalism (confirmation bias). The studies by JSA and Microsoft are tainted by optimism bias, presuming a high likelihood of success, without calculating the likelihood of AI failure. As the Commonwealth Bank example shows, human customer service jobs cannot be adequately managed by AI. It simply creates more work for the downsized labour force

- AI discourse relies on selective use of science: JSA and Microsoft argue that AI will take over specialist jobs. However, these studies have many limitations. They rely on AI modelling and AI-assisted analysis (JSA) and limited AI tasks (Microsoft) that inflate the unproven future value of AI to the media (gain framing)

- AI discourse seeks to eliminate competition: AI discourse is conditioning workers to expect that their jobs will be adapted by automation. AI companies push a discourse of technological supremacy over professions in the arts and humanities, at a time when these sectors are being denied funding, and academic freedom is under attack. The Australian Government’s decision to pay creatives for stolen copyright is welcome, but nothing is being done to stop this theft in the meantime. This political context is ripe for eliminating human competition to AI products

- AI discourse hides the true costs of automation: First, customers pay increased fees for AI services, which they cannot easily opt out of. Second, customer data are stolen for AI profit. The case study of Microsoft shows how AI companies manufacture consent. Copilot relies on extensive user data to build its model. These private data are then used to undermine the stability of jobs in other industries.

Kalleberg and Sørensen illustrate how major changes in the paid labour force impact the broader economic rewards and structure of work.

Defining jobs for automation through limited methods contributes to the deskilling of the labour force. Consequently, automation may have flow-on effects on other aspects of society, such as the economic stability of families, the social mobility of disadvantaged groups, gendered division of labour, and more.

Automation may create precarious working conditions. In the past, this has entrenched poverty, degrading worker rights, and eroding the non-economic aspects of work, such as worker wellbeing. AI discourse does not consider how weaking key industries, such as the arts and humanities, and impeding First Peoples’ rights, may hinder future social progress.

Ultimately, the AI discourse of technological supremacy is a marketing ploy, not an inexorable conclusion. The evidence suggests that AI has minimal utility, with high errors, and low economic returns.

What’s next

In the next post in the Sociology of AI series, I analyse how corporations are strategically using AI discourse to gain policy influence. I’ll delve deeper into the environmental costs of AI, and the ways in which AI companies are encroaching on Indigenous Data Sovereignty.

Learn More

Discover more from The Other Sociologist

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.